Why – and how – to make Next Generation EU (NGEU) sustainable

Frédéric Allemand, Jérôme Creel, Nicolas Leron, Sandrine Levasseur and Francesco Saraceno

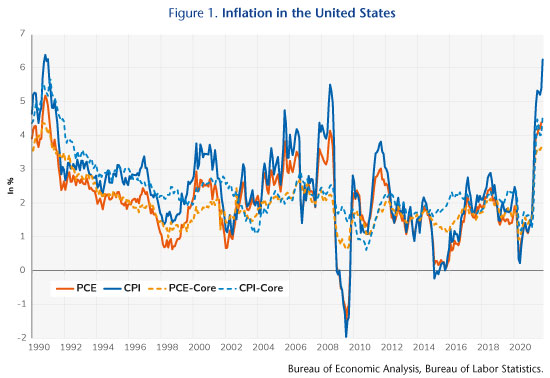

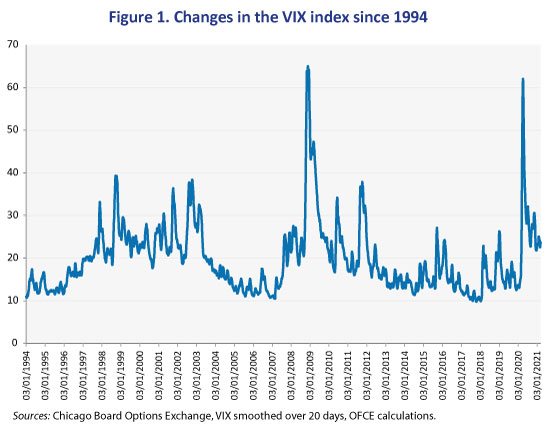

The Next Generation EU (NGEU) instrument was created during the pandemic to finance the recovery and, above all, to ensure the resilience of the European Union (EU). Since then, with the war in Ukraine and its various consequences, the shocks hitting the EU continue to accumulate, in a context where it is also necessary to accelerate the ecological transition and the digitalization of the economy. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has put defence matters back on the front burner, while inflation is giving rise to heterogeneous reactions from member states, which is not conducive to economic convergence, not to mention the monetary tightening that is destabilizing some banks. The Biden administration’s subsidies to US industry have all the hallmarks of a new episode in the trade war, to which the European Commission has responded by temporarily relaxing the rules on state aid. In this uncertain environment, where one shock is following another, the idea of making the NGEU instrument permanent instead of temporary has gained ground. European Commissioner P. Gentiloni, for example, mentioned the idea as early as 2021; it was raised at a conference of the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum in 2022; it appeared at the conclusion of an article by Schramm and de Witte, published in the Journal of Common Market Studies in 2022; and it was mentioned publicly by Christine Lagarde in 2022. There is, however, little consensus on this issue, especially in Germany, where, after the Constitutional Court’s decision in favour of the NGEU on 6 December 2022, the Minister of Finance, Christian Lindner, reminded us that the issuance of common debt (at the heart of the NGEU) must remain an “exception”. As the debate remains open, in a recent study for the Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS), we assessed the economic and political relevance that the implementation of a permanent NGEU-type instrument would entail, as well as the technical and legal difficulties involved.

The implementation of the NGEU has already raised delicate questions of coordination between member states regarding the allocation of funds to the Commission’s various structural priorities (how much to the ecological transition? how much to digitalization?) and between the countries themselves, since the question of a “fair return” never fails to resurface in the course of negotiations. Adding to these coordination difficulties, the first part of our study raises the question of the democratic legitimacy of EU policies when supranational priorities limit the autonomy of national parliaments, starting with fiscal policy, the “material heart” of democracy. The problem of democratic accountability is not new if one considers that supranational rules, such as the Stability and Growth Pact, impose limits on the power of parliaments to “tax and spend”. In fact, the intrinsic logic of coordination is to force political power to conform to functional (macroeconomic) imperatives, which inevitably leads to a form of depoliticization of fiscal and budget policy. The perpetuation of the NGEU must therefore be seen as an opportunity to remedy the depoliticization of EU policies and to move towards a “political Europe” by establishing a supranational level for the implementation of a European fiscal policy.

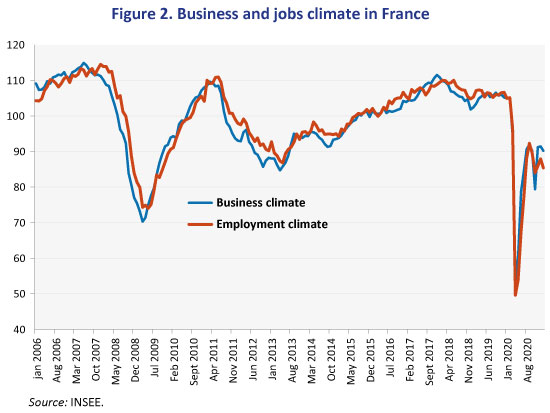

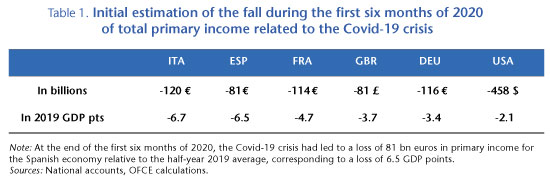

This part of the study also reminds us that while the implementation of the NGEU has been of paramount importance in stimulating a post-pandemic recovery, the economic results are still uncertain since the funds were allocated only relatively recently[1]. It also reveals a change in the mindset of EU policymakers. For the first time, joint borrowing and some risk-sharing have become features of a European fiscal plan. It would be wrong, however, at this stage to see the NGEU as a “Hamiltonian” moment or as the founding act of a federal Europe: the NGEU is limited in scope and duration; it does not take over the past debts of the member states; and it has not created a common spending (investment) capacity. And this is perhaps both its main weakness and its main area for improvement. The pandemic and the strong economic response to it by European states have indicated that they can share common, crucial goals: recovery, resilience, the ecological transition and digitalization. What is missing, however, is a central fiscal capacity to better link the long-term challenges with an instrument adapted to this kind of horizon. Hence the idea of making the NGEU permanent.

As a preamble to a possible long-term establishment of the NGEU, another part of the study raises the issue of determining the main task of a permanent central budgetary instrument. One obvious answer is the provision and financing of European public goods (broadly defined to include the areas of security and environmental protection) that member states may not provide in sufficient quantity, due to a lack of resources and/or externalities. Regarding the provision of public goods, it should be recalled that the preferences of EU citizens are fairly homogeneous within the Union, and that there is a growing demand for some needs to be met at the EU level. For example, 86% of EU citizens are in favour of making investments in renewable energy at the EU level. Even the production of military equipment by the EU is increasingly supported by citizens, with 69% “agreeing or strongly agreeing”. The provision of public goods at the EU rather than the national level would also allow for very tangible economies of scale, for example in the field of infrastructure. Last but not least, this would be justified by the instrument’s capacity to “make Europe” through concrete actions and strengthen the feeling of being European. Any debate on a central budgetary capacity would of course have to be conducted in parallel with that on the reform of the Stability and Growth Pact in order to guarantee the creation of a fiscal space (or additional margins of manoeuvre) in the EU.

The study then points out that there are few options for creating a central budgetary capacity within the current institutional framework. The treaties define a budgetary framework (centred on the multi-annual financial framework, the MFF) for the EU that ties spending to the ability to raise funds, thus severely limiting the ability to raise debt in normal times. The creation of special financial instruments and the decision to spend beyond the MFF ceilings are explicitly linked to exceptional circumstances and cannot be a solution for the recurrent provision of public goods. The 0.6 percentage point increase in the own resources ceiling to 2 percent of GNI [2] ensured that the unprecedented level of borrowing respected the constitutional principle of a balanced budget.

However, this increase was approved only because of its exceptional and temporary nature, as the ceiling on own resources for payments is to be reduced to 1.40 percent of GNI once the funds are repaid and the commitments cease to exist. Even if permanent funding were to be allocated to the NGEU instrument, its capacity to intervene would remain limited. In accordance with its legal basis (Article 122 TFEU), the NGEU is a tool for crisis management whose activation is linked to the occurrence or risk of exceptional circumstances. As a matter of principle, European legislation prohibits the EU from using funds borrowed on the capital markets to finance operational expenditure.

The study examines other legal arrangements that could contribute to the financing of public goods, but whatever legal basis is chosen, (a) the EU does not have a general multi-purpose financial instrument that it could activate, in addition to the general budget, to finance actions and projects over the long term; and (b) the EU cannot grant funds to finance actions outside its area of competence, i.e., it cannot substitute itself for member states in areas where the latter retain competence for their policies. Therefore, if a central budgetary capacity is to be created, it would be necessary to revise the treaties or establish new intergovernmental arrangements (along the lines of the European Stability Mechanism).

Based on the second option, the study proposes that a European public investment agency be created as a first step towards the creation of a central budgetary capacity. This agency would have the function of planning and implementing investment projects, in cooperation with the member states. Under EU legislation, the agency would not have full control over policy choices but would act mainly within the limits set by the roadmaps of the EU institutions. Nevertheless, it would have the administrative capacity to design public investment projects that the Commission currently lacks, and it could be given control over allocating grants, developing technical guidelines, monitoring cross-compliance, etc.

The last part of the study reminds us, nonetheless, that even substantial progress in developing a central budget capacity should not obscure the need for national budget policies to be implemented as well, and that close coordination between them is needed. While increasing powers are being transferred to the European level in the area of public goods, as can be seen for example with the European Green Pact and with the targeting of NGEU spending towards greening and digitalization, there is still a need to coordinate national governments’ policies with each other and with the policies implemented at the central level. Policy coordination, which necessarily limits the autonomy of national parliaments, raises the question of the democratic legitimacy of EU policies and may lead to a form of depoliticization of fiscal policy. This would become even more problematic if the EU were to transfer to the supranational level some of the decisions about which public goods to provide and from whom to finance them. To avoid delinking the strengthening of European macroeconomic policy on public goods with the democratic dimension of this orientation, nothing less than a quantum leap in the creation of a political Europe, with two democratic levels, is probably needed, with genuine European democracy –- because it would be based on a real European parliamentary fiscal power, which would in turn be linked to the preferences of the European electorate –- but fully articulated with the national democracies with their recovered fiscal margins.

[1] The inconsistency between the need to revive the European economy after the pandemic and a very gradual disbursement of funds is discussed by Creel (2020).

[2] GNI: Gross national income, defined as GDP plus net income received from abroad for the compensation of employees, property, and net taxes and subsidies on production.