Where does the European Union stand?

By Robert Boyer, Director of Studies at EHESS and the Institut des Amériques

Speech at the “European Political Economy and European Democracy” seminar on June 23, 2023, at Sciences Po Paris, as part of the ‘Théorie et Economie Politique de l’Europe’ seminar, organized by Cevipof and OFCE.

The aim of the first study day of the Theory and Political Economy of Europe seminar is to collectively engage in a work of overall theoretical reflection, following on from the thematic sessions of 2022, by continuing the multidisciplinary spirit of the seminar. The aim is to begin outlining the contours of the two major blocks of European political economy and European democracy and to identify the points of articulation between them. And to prepare for multidisciplinary writing with several hands.

An apparent paradox

During the various and rich interventions pointing out the shortcomings, dilemmas, and contradictions that characterize the processes of European integration, a central question seems to emerge:

“How has a politico-economic regime in permanent disequilibrium, which has become very complex, been able, until now, to overcome a large number of crises, some of which threatened its very existence?”

A brief review of the current situation is enlightening and makes it more necessary to seek out the factors likely to explain this resilience, which never ceases to surprise researchers and specialists, foremost among them many economists. In the face of a succession and accumulation of poly-crises and rising uncertainties, is it reasonable to anticipate that the European Union (EU) will continue its current course, protected by the mobilization of the processes that have ensured its survival, not least thanks to the responsiveness demonstrated by both the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Commission since 2011?

Baroque architecture full of inconsistencies

The various speakers highlighted many of them:

- The European Parliament is a curiosity: it is an assembly with no fiscal powers. Would giving it this power be enough to restore the image of democracy on a European scale?

- The EU issues a common debt even though it has no direct power of taxation: isn’t this a call for an embryonic federal state? Is there a political consensus on this path?

- This debt corresponds to the financing of the Next Generation EU plan, which recognizes the need for solidarity with the most fragile countries, in response to a common “shock” that does not lend itself to the moral hazard so feared by the frugal countries of the North. Yet it is the result of an ambiguous compromise, with two opposing interpretations: an exception that must not be repeated for the North, and a founding, Hamiltonian moment for the South.

- It is not very functional or democratic for the European Parliament to vote on Community expenditure, but for national parliaments to vote on revenue.

- Does it make sense to have a multiannual program adopted by an outgoing assembly of the European Parliament, which will then be binding on the next one?

- The ceiling set for the European budget limits the financing of European public goods, which should compensate for and go beyond the limitation on the supply of national public goods in the application of the criteria governing national public deficits and debts.

- At the European level, the quest for more democracy tends to focus on the question of political control over the Commission and the ECB, whereas social democracy has in the past been a critical component in the legitimacy of governments at the national level.

- The same applies to the question of corporate governance in Europe, a forgotten issue on the European agenda that is regaining a certain interest in the face of the transformations brought about by digital technology and the environment.

- Competition policy is often perceived by economists as one of the Commission’s key instruments since it is an integral part of the construction of the single market. Yet legal analysis shows that competition is not a categorical imperative, defined finally, but a functional concept that evolves over time. So much so, that the Commission can declare that today it is at the service of the environment.

- The Commission is usually criticized for its role as a defender of the acquis, its taste for excessive regulation, its technocratic approach, and its inertia. And yet, since 2011, it has continued to innovate in response to successive crises, to the point of having relaunched European integration.

- The ECB was founded as the embodiment of an independent, typically conservative central bank, with a monetarist conception of inflation. And yet, without changing European treaties, the ECB has been able to innovate and effectively defend the Euro.

- The EU Court of Justice and national constitutional courts do not have the same interests and legal conceptions, but so far, no head-on conflict has produced a blockage in European integration. Is this sustainable?

- Is the distribution of competencies, fixed by the treaties and de facto adjusted as problems and crises arise, satisfactory and up to the challenges of the industry, the environment, public health, and solidarity in a dangerous and uncertain international environment?

- The “European Constitution” is not a constitution, because integration has proceeded via a series of international treaties. How can we explain the fact that these treaties have been imposed when member countries could have coordinated through the OECD, EFTA, the IMF, or ad hoc agreements (European Space Agency, Airbus, Schengen) with no overall architecture?

Reasons for surprising resilience

We need to identify the factors that can account for the perseverance that lies at the heart of continental integration and ask ourselves whether they are sufficiently powerful to overcome the current multi-crises.

- From the outset, the project was a political one, aimed at halting Europe’s decline in the wake of the two world wars. But in the absence of political agreement on a common defense, the coordination of economic reconstruction was seen as a means to this end. In this respect, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has strengthened ties between governments, even if it means inverting the hierarchy between geopolitics and economics and bringing back to the forefront the possibility of Europe as a power.

- Conflicts of interest between nation-states are at the root of a succession of crises, which are overcome by ad hoc compromises that never cease to create further imbalances and inconsistencies, which in turn lead to another crisis. In a way, the perception of incoherence and incompleteness is a recurring feature of European construction. However, the configuration can become so complex and difficult to understand that it can overwhelm the inventiveness of the collectives that are the various EU entities and their ability to coordinate. By way of example, a genuine EU macroeconomic theory has yet to be invented, and this is a major obstacle to the progress of integration.

- European time is not homogeneous. Periods when new procedures are put in place after a breakthrough give the impression of bureaucratic, technocratic management at a distance from what citizens are experiencing. By contrast, open crises forbid the status quo, as the very existence of institutional construction is at stake, with the stratification of a large number of projects and their incorporation into European law. This experience of trial and error is the breeding ground that enables the Commission, for example, to devise solutions to emerging problems. As a result, the equivalent of an organic intellectual seems to have emerged from this collective learning over an extended period. This is one interpretation of the paradoxes mentioned above.

- European Councils, the Court of Justice, the ECB, and the European Parliament all play their part in this movement, but it is undoubtedly the European Commission that in a sense represents the European, if not the general, interest. The fact that it has the power to initiate regulations and manage procedures gives it an advantage over other bodies. Indeed, many governments would be satisfied with inter-state negotiations, with no common ground to build on, and would go it alone. Failure to find a compromise solution would mean the simple disappearance of the EU. Similarly, without the “whatever it takes” approach, the ECB would have disappeared with the Euro. The major crises offer a strong incentive to move beyond dogmatic posturing in favor of a re-hierarchization of objectives and the invention of new instruments.

- Finally, there are two sides to the proliferation of regulations, procedures, and European agencies attached to the Commission. On the one hand, they give rise to the diagnosis of poorly controlled management and the harsh judgments of defenders of national sovereignty. On the other hand, they are also factors in the reduction of uncertainty and the creation of regularities that coordinate expectations in a context where financial logic generates bubbles and macroeconomic instability. In a way, a certain redundancy in a myriad of interventions is a guarantee of resilience. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM), for example, was a way of circumventing the ECB’s delay in recognizing the need for vigorous intervention. So the complexity of the EU can also mean redundancy and resilience.

- Political power plays a crucial role in the development of European institutions. It intervenes in the framework of councils and summits. So far, in the national political arena, governments favoring further integration have prevailed: this is sometimes one of the only markers of their policy that survives the various periods. As a result, a collapse of the EU could mean the loss of their credibility. It would be dramatic for a government to be held responsible for the failure of a project that has been built up over decades. This is perhaps a hidden source of the permanence of European institutions. What is more, “Brexit” far from marking the end of the EU has rather closed ranks, especially as the expected benefits for the UK have not manifested themselves. Beware, however, that the polarization and division of societies between the winners and losers of trans nationalization has favored the breakthrough of parties defending strong national sovereignty, i.e. a countertrend that forbids prolonging the hypothesis of a lasting hegemony of pro-European parties.

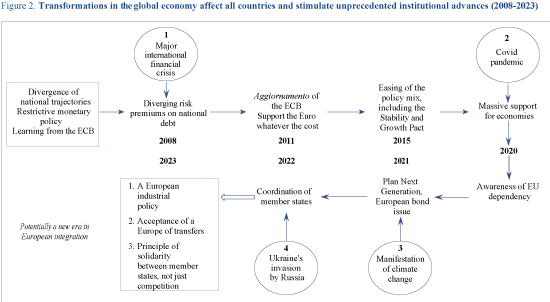

- Finally, the succession of financial crises, the return of pandemics, the harshness of the confrontation – not only economic – between the United States and China, the growing awareness of the environmental emergency, and the installation of a new inflation generated by recurring scarcities, which risks being aggravated by the transition to a war economy, are all factors in a dual awareness. On the one hand, common interests tend to outweigh disagreements between member countries. On the other hand, each of them carries little weight in the confrontation with the United States, which has become openly protectionist, and China, with its dynamism in emerging productive paradigms. The EU needs to be a geo-economic and political player in its own right. This explains the Commission’s activism since Covid-19. Citizens have benefited from this new impetus, with a common strategy on vaccines, for example. For their part, the governments of the most fragile economies have benefited from European solidarity, which has counterbalanced the principle of regional competition.

Historical bifurcation, polycentric governance, or nationalist withdrawal?

The processes described above can recombine to form a wide variety of trajectories. Prediction is not possible, as it is the strategic interactions between collective actors that will determine how to overcome the EU’s various crises. It is possible to imagine three more or less coherent scenarios.

- Towards an original federalism disguised by a myriad of technical coordination procedures

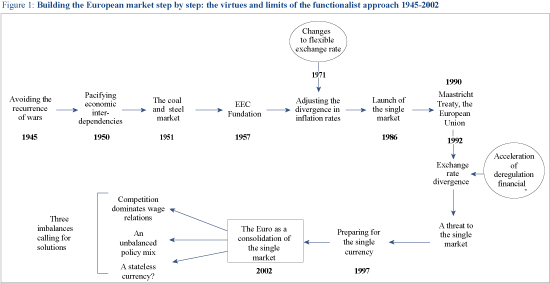

This first scenario is based on three central assumptions. Firstly, it marks the end of reliance on neo-functionalism, whereby governments must be the servants of the necessities imposed by economic interdependence between nation-states (figure 1). The sphere of politics pursues its objectives, even if governments must contend with economic logic. Secondly, it draws the consequences of technological, geopolitical, health, and environmental transformations that threaten the stability of societies and the viability of their socio-economic regimes. Pooling resources increases the chances of success for all participants in European programs. Finally, this first scenario extends the trends already observed since the outbreak of the pandemic.

As far as the word federalism has a repulsive effect on public opinion, which is influenced by populist nationalism, the practice of enhanced cooperation does not have to be accompanied by an appeal to the federalist ideal. Instead, skillful rhetoric must convince citizens that the EU ensures their protection and opens new common goods. These advances in no way subtract from the social, economic, and political rights guaranteed at the national level. Charismatic politicians must be able to resist anti-EU rhetoric that feeds on the relative powerlessness of national authorities overwhelmed by transnational forces beyond their control.

- Adapting polycentric governance at the margins, far from a Europe of power

This second scenario, on the other hand, assumes that the current period will be one of continuity with the long-term trajectory of European integration. The polycentrism of EU entities is a vector of pragmatic adaptability to emerging issues, without the need to centralize power in Brussels, as suggested by the diversity of European agency locations. Trial and error, the multiplication of ad hoc procedures, and the possible use of enhanced cooperation on issues involving a fraction of member countries are all sources of adaptation in the face of the repetition of events potentially unfavorable to the EU.

This considers the fact that negotiating new European treaties seems a perilous mission, that public opinion judges the EU on the basis of its contribution to the well-being of its populations rather than the transparency and coherence of its governance, and that an imperial conception is illusory. One might be tempted to invoke a form of catallaxy applied not to the economy and the market, but to the political sphere: the interaction of highly varied processes, without central authority, eventually leads to a roughly and provisionally viable configuration. The English expression “muddling through” aptly captures this pragmatism, marked by the renunciation by public decision-makers of the need to spell out an objective and a goal, if only to persevere in being.

Success is not guaranteed. Firstly, past successes are no guarantee of their continuation into the future. Secondly, there is no guarantee that a pragmatic solution will be found in the face of an avalanche of unfavorable events since the affirmation of an objective may prove to be a necessary condition for lifting the prevailing uncertainty as to the outcome of both institutional and economic crises. Last but not least, how can we politically legitimize an order whose logic and nature elude decision-makers? Isn’t this powerlessness the breeding ground for populist voluntarism?

- National and European elections: a nationalist majority redesigns a different Europe

This third scenario is based on an analysis of changes in the objectives of government following recent elections in Europe. Both in the South (Italy) and in the Scandinavian countries (Finland, Sweden, Denmark), coalitions have come to power dominated by parties opposed to immigration, defenders of national identity, and, in short, reluctant to delegate new powers to the EU. In this, they join the authoritarian, nationalist governments of Central Europe (Hungary, Poland). In the European Parliament elections of 2024, could this movement result in the loss of a majority in favor of the EU’s current policies, to the benefit of a new majority bringing together nationalist parties that are very diverse, but share the same obsession: to block the extension of EU competences and repatriate as many of them as possible to the national level?

Russia’s war against Ukraine has brought the imperative of defense to the fore, an area in which the EU has made little progress. Does not this mean that NATO is becoming central to the political organization of the old continent, to the detriment of the economic objectives pursued by European integration?

These hypotheses, derived from the 23 June 2023 CEVIPOF and OFCE meeting? call for a follow-up, as the questions to be clarified are so many and quite difficult indeed. Cross-disciplinary analysis is more necessary than ever.

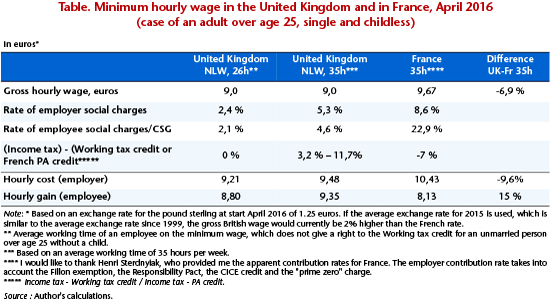

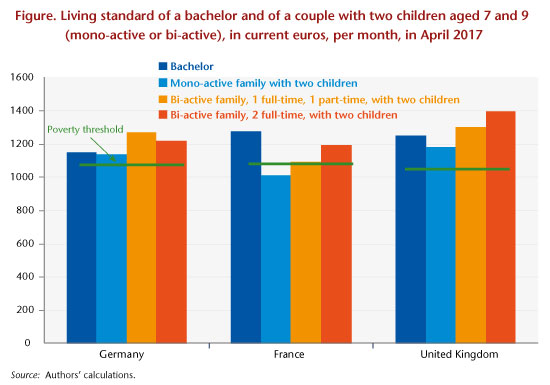

From the point of view of the relative position of minimum wage earners in relation to the general population, our study highlights the rather favourable situation of the United Kingdom. The living standard there is comparatively high: all the families considered in our typical cases have a standard of living above the poverty line, on the order of 30% higher for a family where both parents work full-time at the minimum wage. The gain from taking up a job is, as in France, high, while it is low in Germany in all the configurations.

From the point of view of the relative position of minimum wage earners in relation to the general population, our study highlights the rather favourable situation of the United Kingdom. The living standard there is comparatively high: all the families considered in our typical cases have a standard of living above the poverty line, on the order of 30% higher for a family where both parents work full-time at the minimum wage. The gain from taking up a job is, as in France, high, while it is low in Germany in all the configurations.