With the latest national accounts published on 22 December 2022 showing a 0.3% fall in GDP in Q3 of 2022, following a 0.1% rise in the previous quarter, concerns are growing that the British economy may be entering a recession. In an inflationary context that has been exacerbated since early 2021, in particular due to the rise in energy prices, successive governments, led by Johnson, Truss and then Sunak, have introduced measures to support the economy in order to cushion the shock to purchasing power and temper its negative impact on activity.

On 17 November, the Sunak government, which took office on 24 October, presented a budget that contrasts sharply with the orientation of its predecessor, led by Liz Truss, who resigned after only 44 days in office. Indeed, the former government’s announcement of a sweeping budgetary plan to support households and businesses in the face of the energy crisis and to lower taxes over a five-year period left doubts about its viability in the absence of financing, sending panic through the markets.

For the medium term, the budget presented by the current British Chancellor Jeremy Hunt takes a line opposite to that promoted by the former government and relies instead on austerity to prolong the effort at fiscal consolidation undertaken after the Covid-19 shock and to guarantee control of the public finances over the next five years in a context of rising interest rates. The government is nonetheless caught between conflicting objectives: between support for households and business in the short term to mitigate the effects of the inflationary shock, and the desire to guarantee the medium-term stability of public finances. The plan announced on 17 November is thus divided into three parts.

A State buffering inflation

A first set of short-term measures has been taken to support households faced with rising prices, particularly for energy. The government continued the measure taken by the previous government for this winter, namely capping gas and electricity prices. Thus, during the winter of 2022/2023, households will see their energy bills limited to an average of £2,500 per year, which represents a saving of £900 borne by the public purse, at a total cost of £24.8 billion. This cost is of course uncertain as it depends on the price of energy on the international markets. The provisions will be less generous in the 2023/2024 financial year[1], when the cap rises to £3,000 per annum, reducing household support by £500 and cutting the measure’s overall cost to £12.8 billion according to the budget. Raising the cap should thus save £14 billion in 2023/2024 compared to the Truss government’s announcement of £26.8 billion in tax shields for the year.

The government plans to plough 90% of this £14 billion savings in 2023/2024 back into support schemes for the most vulnerable households, with payments to 8 million households: means-tested benefit recipients will receive payments of £900, pensioners £300, and recipients of disability allowance £150. The government has also decided to follow the Low Pay Commission’s recommendation of a 9.7% rise in the minimum wage in April 2023, and social benefits and state pensions will rise in line with inflation in October 2022, i.e. by 10.1%.

On the other hand, in order to support the productive sector, the government has maintained the Truss government’s support scheme for companies facing rising energy costs, while cutting the scheme back. The measures, introduced for six months between 1 October 2022 and 31 March 2023, should cost £18.4 billion (compared with £29 billion planned by the previous government).

The government had not yet decided on 17 November 2022 whether to renew the business support measures for the 2023/2024 financial year, and an evaluation was to be carried out to inform future decisions. On 9 January 2023, Sunak’s government clarified its intentions regarding the sustainability of the “energy shield” for businesses: it will be maintained during the 2023/2024 financial year but will be considerably reduced compared to current provisions. This is due to their cost, which Jeremy Hunt considers unsustainable for the country’s public finances. So £5.5 billion is budgeted for the 2023/2024 financial year.

In total, the energy shield and support for vulnerable households and businesses will receive £43.2 billion in 2022/2023 and £30.6 billion in 2023/2024. Adding in the measures already taken by the Johnson government since March 2022, the public commitment comes to £64.2 billion in 2022/2023 and £45.3 billion in the following year. On a calendar basis, this support amounts to £48.2 billion in 2022 (or 2.2 percentage points of 2019 GDP) and £50 billion in 2023, making the UK one of the most generous countries on the continent of Europe in terms of supporting the economy in the face of an inflationary shock[2], although slightly later than others.

The State – Guarantor of the sustainability of the public finances

In addition to this short-term support for the economy, which implies a highly expansionary policy, the new government has expressed its concern to ensure a “sustainable” trajectory for the public purse, i.e. one that leads to both a fall in the debt/GDP ratio over a five-year period and a reduction in the deficit to below 3% of GDP. In order not to contradict the support measures decided for the 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 financial years, when there is a high risk of the British economy entering a recession, the government has taken care to start tightening fiscal policy only in 2024/2025.

The fiscal austerity plan provides additional resources that rise progressively to £55 billion in 2027/2028, which is split between 45% in tax increases (£25 billion in 2027/2028) and 55% in spending cuts (£30 billion). For households, the government plans to lower the 45% income tax threshold from £150,000 to £125,140 in April 2023, to freeze income and inheritance tax rates at current levels for a further two years until April 2028, to quadruple tax credits on dividends and capital gains from 2024/2025, and to limit the previous government’s reductions in property transaction duty to 31 March 2025.

The 19% corporation tax cut envisaged by Liz Truss is cancelled, and the rate will rise to 25% in April 2023, as announced before Truss took office. The rate of social security contributions will remain at the current level between April 2023 and April 2028. In addition, energy companies’ excess profits will be taxed more heavily, with the current arrangements extended to March 2028 and the tax rate increased from 25% to 35% on 1 January 2023 (£14 billion expected in the 2023/2024 financial year). In addition, a 45% tax on the profits of electricity producers will be introduced in January 2023 (£4 billion expected in 2023/2024). The government nevertheless remains concerned about inflationary pressures on production and has planned a cumulative support to business of £13.6 billion until 2027/2028, mainly by means of local taxes.

On the expenditure side, the government plans to implement a savings plan based mainly on slowing down the growth in public spending, which should not exceed inflation by more than 1 point. However, the effort will be implemented from the 2025/2026 financial year onwards, while some spending on priority public services (health, social protection and schools) will rise over the next two financial years.

Calming the markets

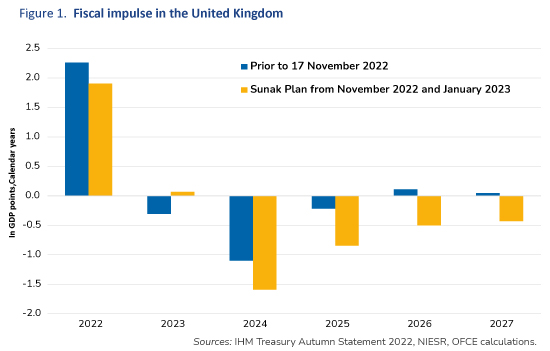

In terms of the fiscal impulse, the calendar year 2022 looks to be the most expensive ever in response to the emergency created by the spectacular rise in inflation (Figure 1). In 2023, the redeployment of almost all the resources freed up by the reduction in the energy shield to the most vulnerable households and the maintenance of a “business shield” will make it possible to ensure the government’s overall commitment to the emergency plan, without however generating any significant additional stimulus. On the other hand, in 2024, the withdrawal of short-term aid schemes and the entry into force of the fiscal savings plan will generate a very negative fiscal impulse of -1.2 points of GDP. By 2027, the provisions announced by the Sunak government will see a negative fiscal impulse of around 0.5 percentage points of GDP each year.

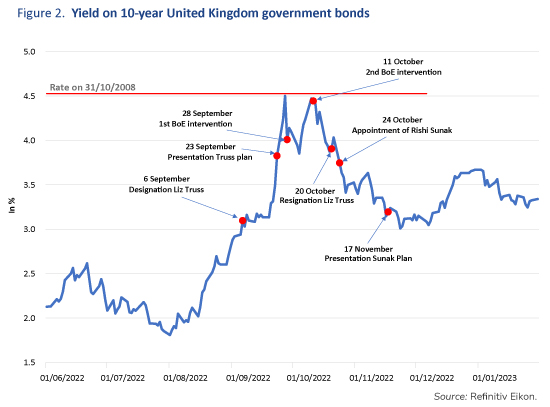

However, it is hypothetical whether these projections will be attained over a five-year horizon. First, a new budget will be presented on 15 March. Second, a general election will be held by the end of 2024. There is therefore great uncertainty about the implementation of this plan. Nevertheless, the November 2022 announcements achieved the objective of calming the financial markets, as by 1 December 2022 the yield on 10-year government bonds had fallen back to its level prior to the Truss government’s autumn budget statements (Figure 2). In the meantime, the pound, after depreciating by 5% between 6 and 28 September 2022, also returned to its level of early September.

[1] In the United Kingdom, the financial year starts on 1 April and ends on the following 31 March.

[2] See “From hot to cold”, Analysis and Forecasting Department, Perspectives 2022-2023 pour l’économie mondiale et la zone euro [in French], 12 October 2022, pp. 35-41.