By Éloi Laurent and Paul Malliet

On the eve of the climate summit organized by the Biden administration on 22 and 23 April, which will be attended by 40 heads of state and government, we offer here some initial reflections on a critical issue facing international climate negotiations: how should the effort to reduce emissions be shared between countries within the framework of the United Nations?

The news on the climate emergency front at the start of 2021 is mixed, which might not be so bad: the new US administration’s willingness to assume leadership on the climate agenda, within a multilateral framework, contrasts with the obscurantist obstructionism of the previous administration. Furthermore, 110 countries have announced their commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, with China sharing this goal, but by 2060[1].

But in order to close the gap between the speed being attained by natural energy systems and the inertia inherent in today’s economic and political systems, these encouraging geopolitical dynamics must pick up the pace. In this respect, one key indicator is the gap between the status quo of current policies (“business as usual”) and the full implementation of the commitments made in the wake of the Paris Agreement: if all the commitments currently formulated and described in the States’ respective national contributions were really met, we would be heading towards 2.6° of warming by the end of the century; if everything continues as it is today, we are heading towards 2.9° of warming. As it stands today, the Paris Agreement (which has led to undeniable progress) is therefore worth only 0.3 degrees, or about a decade and a half of warming at the annual rate observed since 1981[3].

A new global climate strategy must therefore be developed and implemented, and it needs to bear fruit starting from the COP-26 meeting next November in Glasgow. The Biden administration is organizing a summit on 22 and 23 April, which will be attended by 40 heads of State and government. In line with the American Jobs Plan, the agenda for this meeting emphasizes the economic gains expected from decisive climate action. But it fails to address the need for coordination: how should national efforts at emissions reduction be shared among the world’s countries? On the basis of what criteria? In other words, how can we map out the path towards the orientation indicated by the Paris Agreement?

We are proposing here an embryonic reflection (which we will elaborate on in the run-up to COP-26) on the question which, in our view, is now the raison d’être of international climate negotiations: how to share the effort to reduce emissions between countries within the framework of the United Nations?

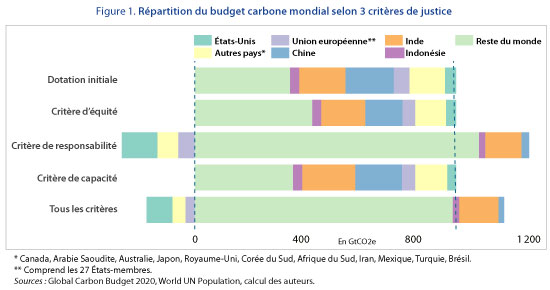

In the light of the IPCC’s Special Report on 1.5° published in 2018, we determine a global carbon budget, which in 2019 amounted to 945 GtCO2e; this corresponds to an intermediate target between the 1.5° and 2° budget associated with the 67th percentile of the Transient Climate Response to Emissions (TCRE),[4] in line with the goals set in Article 2 of the Paris Agreement.

The question of the fair distribution of this global carbon budget has been the subject of numerous studies (for a summary and proposals, see for example Bourban, 2021), but there is currently no work that integrates a complete vision of the three justice criteria identified in the academic literature – equity, responsibility and capacity – in order to determine an operational distribution of national efforts to avoid the climate catastrophe.

With this in mind, we focus our analysis on the top 20 emitting countries,[5] which accounted for 77% of emissions in 2019. We assume that the emissions reduction target will be shared by all countries by 2050 and that the carbon budget therefore covers the next 30 years, which translates into an average annual budget of around 30 GtCO2e (for comparison, 36 GtCO2e were emitted in 2019). We take as a starting point an equal distribution among all members of humanity in 2019, meaning an initial allocation of 122.5 tCO2e up to 2050, i.e. about 4 tCO2e per year (a country’s budget being the aggregation of the individual allocations of its total population).

We interpret the equity criterion as meaning equal access of the world’s citizens to the greenhouse gas (GHG) storage capacity of the atmosphere (this corresponds to a universal carbon endowment corrected for each major emitter for its population and for population growth by 2050).

Our responsibility criterion is the amount of GHGs already emitted since 1990 in consumption, thus combining a spatial justice criterion with a temporal criterion, reflecting the global as well as the historical responsibility of individual countries.

Finally, the capacity criterion is expressed here by the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI), which by construction ranges from 0 to 1, and which we relate for each country to the world average (which in 2019 was 0.737). Thus, countries whose HDI is lower than this world average would see their budget increase in proportion to their human underdevelopment, and vice versa for developed countries, i.e. they would see their budget decrease in the opposite direction (Figure 1).

The equity criterion generally operates a reallocation from countries with a falling population to those with a rising population, which are almost entirely located in sub-Saharan Africa. In this respect, based on this criterion China undergoes a reduction in its budget of 44 GtCO2e (almost 25%), while the rest of the world benefits from an increase of 86 GtCO2e. The responsibility criterion appears to be the main determinant leading to a reallocation of the global budget between countries, with a transfer of nearly 263 GtCO2e from the OECD countries to the so-called developing countries. The capacity criterion also leads to a reallocation towards developing countries, but much less (almost 34 GtCO2e in total)[6].

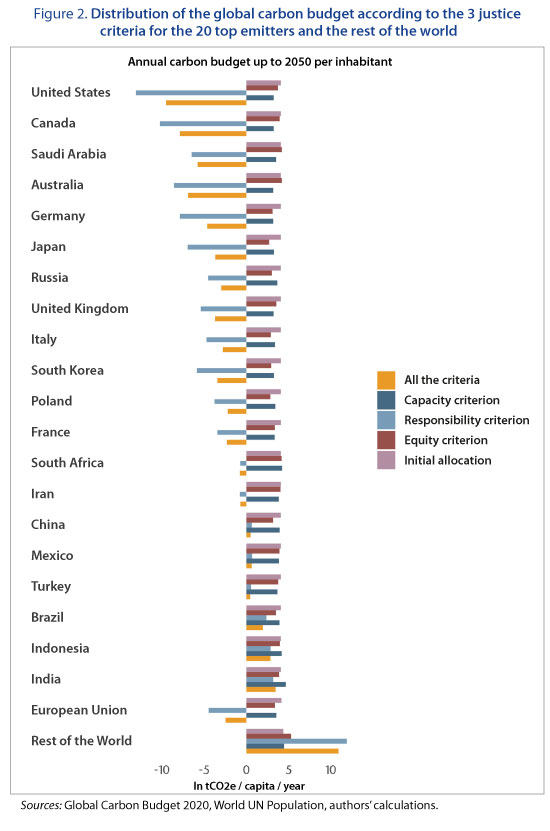

Thus each criterion plays out differently (either by the nature of the rebalancing or by its extent), suggesting that the interplay of this relatively simple set of three criteria does indeed enable different understandings or conceptions of climate justice to be translated into a distribution of the burden of the mitigation effort (Figure 2).

Note: Each bar indicates the effect of each criterion, taken independently of the others, on the average annual carbon budget per country. For example, while each American citizen has an initial allocation of 4 tCO2e, the equity criterion leads to this budget being reduced to 3.73 tCO2e, the application of the responsibility principle leads to the initial allocation turning negative and corresponding to a debt of 13 tCO2e, and the capacity criterion reduces the initial allocation to 3.25 tCO2e. The aggregation of these different criteria results in a total negative budget[7] of 9.5 tCO2e per capita per year.

However, this representation does not tell us anything about the future emissions trajectories of the different countries, the instruments that will be implemented and the justice criteria specific to each country that will govern the deployment of these instruments. In a second stage of our analysis, we will propose possible distributions of the budget globally determined for France in order to appreciate the issues of climate justice, moving from the global to the national and finally to the individual. In any case, this first step informs us about what could be a fair distribution capable of more explicitly capturing the guiding principle of the international community since the Rio summit in 1992 of “shared but differentiated responsibility”.

In the light of this initial analysis, one point seems perfectly clear: if the new US administration does indeed intend to reassume global climate leadership, in association with the European Union, it will have no choice but to face the existence of a climate debt to the rest of the world. Given its level, it is illusory to believe that this can be offset by hypothetical negative emissions, and should therefore be subject to one form or another of compensation[8]. This could for example mean much more significant amounts than those currently paid into the Green Climate Fund, which is still largely underfunded in relation to the initial stated ambition of reaching a budget of $100 billion in 2020.

A second point is that China can no longer claim to be a major emerging country in the climate negotiations, with an exploding emissions trajectory that is supposedly part of its right to development and economic growth. In 2020, and taking into account all the criteria adopted, its carbon budget, at 21 Gt, would be close to that of Indonesia, which has one-fifth of China’s population.

It seems that the Biden administration wants to mark Earth Day on 22 April with two announcements: one concerning new 2030 climate ambitions for the United States and the other concerning further emissions reductions by the invited heads of State and government. These announcements will be fully credible only if the US manages to reconcile its national ambition with its global responsibility, and thereby convince China to do the same.

[1] This represents about 50% of the population as well as global GHG emissions.

[2] Climate Action Tracker, December 2020 projection https://climateactiontracker.org/publications/global-update-paris-agreement-turning-point/

[4] The TCRE translates the average variation of average temperature with the stock of carbon in the atmosphere with an associated probability. In our analysis this translates into the following: There is a 67% chance that the carbon budget in question will lead to a temperature rise limited to 1.75°.

[5] The top 20 emitting countries in 2019 were: the United States, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Germany, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, Italy, South Korea, Poland, France, South Africa, Iran, China, Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, Indonesia, and India. We also include the 27-Member European Union to provide a basis for comparison.

[6] Note that among the countries we distinguish, only India would see its budget increase, but just by 3%.

[7] A negative budget here reflects the fact that the historical emissions taken into account via the responsibility criterion is higher than the current carbon budget allocated via the other criteria.

[8] The question of the monetary valuation of past emissions is a research topic in itself that we do not address in this text. As an illustration, a valuation of one tonne of CO2 at $1 would lead to a global amount of $263 billion, and for a valuation at $20, it would be $5260 billion.

Leave a Reply