by Evens Salies and Sarah Guillou

After years of hesitation, the German parliament has just introduced a tax scheme to promote investment in R&D. The decision precedes the Covid-19 crisis, but it may well be heaven-sent for German business.

What factors motivated Germany to take such a decision, four decades after the United States and France, when it is among the world’s leading investors, in terms of both R&D and innovation? Is this yet another instrument to boost its competitiveness? And what will be the repercussions on R&D spending in France?

The German tax incentive, which came into force in January 2020, offers companies a tax credit equal to 25% of the declared R&D expenditure. The base is narrower than for France’s research tax credit (CIR), since in Germany only wages are taken into account (including employer social security contributions).[1] The 25% rate is, however, close to the French rate (30%). A company’s eligible expenses are capped at two million euros; and the tax credit for each firm will be limited to 500,000 euros (subcontracting is subject to slightly different treatment). When a group has several subsidiaries benefiting from the system, as part of a joint research programme, the total eligible expenses are capped at 15 million euros (for a tax credit of 3.75 million).

By way of comparison, among French companies who carry out R&D, SMEs receive an average of 131,000 euros for the CIR credit, mid-caps [fewer than 5,000 employees] 742,000 euros, and large corporations 5.6 million, according to the MESRI’s figures. The highest amounts exceed 30 million euros (with few companies in this category), but do not go much higher, because the CIR rate falls from 30% to 5% of eligible R&D expenditure beyond the base threshold of 100 million euros. Estimates of the annual loss in taxation for Germany (before taking into account the macroeconomic effects) could amount to as much as five billion euros. This is 80% of the French CIR credit, and on the same level as the R&D tax incentives in the United Kingdom. Without the cap, the scheme would cost the German federal government around 9 billion euros.[2]

The characteristics of the scheme and the high level of German private R&D raise questions about the Parliament’s real motivations. Indeed, one could wonder why it did not opt for an “incremental” system, that is, base itself on the increase in eligible R&D expenditure, as in the United States, or in France until 2003. Admittedly, an incremental system would not support firms whose R&D is stagnating or falling (in which case direct aid is more effective), but it avoids the windfall effects of France’s CIR credit (Salies, 2017). The cap limits, but does not eliminate, these effects.

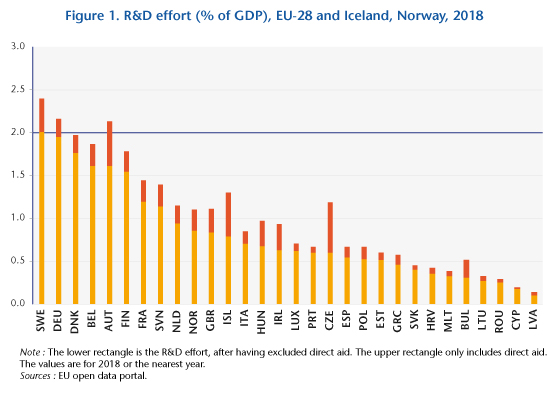

The level of private R&D spending is significantly higher in Germany than in any other EU Member State (62.2 billion euros, excluding direct grants). France is far behind (27.5 billion euros), followed by Italy and Sweden (respectively 12.8 and 9.6 billion). A comparable ranking is obtained, for Germany, France and Italy, if we measure the R&D effort (expenditure relative to GDP; Figure 1). Germany is at almost the same level as Sweden (resp. 1.92 and 2.01 points). Next come Denmark, Belgium, Austria and Finland. France is in 7th position with 1.44 points and Italy 13th with 0.71 point. Private research in Germany (excluding subsidies) is only 0.08 GDP points below the 2% threshold set at the Barcelona European Council in 2002 (the “Lisbon strategy”), which Sweden alone has achieved. If subsidies are included, the private sector exceeds this threshold. Since 2017, Germany’s domestic expenditure on R&D (private and public) has also exceeded the 3% threshold. The argument advanced in 2009 by Spengel and Grittmann from ZEW that a tax incentive would allow German companies to overcome private underinvestment in R&D is therefore not convincing, at least from a European perspective.

At the global level, three countries are of course doing better than Germany: the United States, China and Japan, where the private sector spends 1.6 euros for every euro spent by Germany. However, if the motivation of Germany’s Parliament for introducing a tax incentive was to catch up with these countries, it would not have done so only 40 years after the United States!

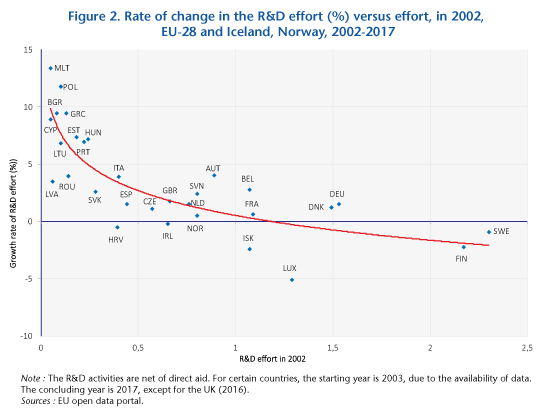

The introduction of a tax incentive for R&D is less surprising if we consider changes in the R&D effort. We have calculated the average growth rate of the R&D effort for the 27 current Member States plus the United Kingdom, Norway and Iceland over the period 2002-2017 (Figure 2).

The curve through the cloud (logarithmic adjustment) reveals an almost inverse relationship between the rate and the effort in 2002, suggesting a convergence of R&D efforts. Obviously, many countries are in a period of catch-up with respect to investing in research. Most of them are small, but the whole is significant. For example, in 2017 countries where the R&D effort grew at a rate at least equal to Germany’s (1.52%) spent 82.8 billion euros (subsidies included), or 1.2 times Germany’s expenditure (68.7 billion).[3] The R&D effort of these countries amounted to 0.8 point of GDP in 2017.[4]

Could the German CIR credit thus be a response to the slowdown in the country’s spending on R&D? R&D expenditure behaves like other capital expenditure, i.e. it slows as the level rises. Furthermore, the more countries have a high level of domestic spending on R&D, the more they invest in R&D abroad. This results from the fact that R&D expenditure is mainly by large corporations and multinationals; we could cite, for example, Alphabet, Volkswagen and Sanofi, which in 2019 spent, respectively, 18.3 billion, 13.6 billion and 5.9 billion euros on R&D according to figures from the EU Industrial R&D Scoreboard. It is notable that the big multinationals open R&D centres abroad to get closer to their export markets, as well as for the bargaining power that these investments provide vis-à-vis local governments (see the report by UNCTAD WIR, 2005). All the major pharmaceutical firms (Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis, Eli Lilly) have established clinical research laboratories in India. Even France’s power supply firm EDF has an R&D centre in Beijing, dedicated to networks, renewable energies and the sustainable city. While this does not necessarily amount to substitution with domestic R&D, it does indicate that there is a kind of plateau in a given country for a company’s R&D expenditure. The German measure is probably motivated by global competition to attract new R&D centres. This is also the stated objective of France’s CIR credit.

Does the enactment of a “German CIR” credit in favour of R&D bode well for France’s competitiveness? Germany has a comparative advantage in the manufacturing sector, which invests heavily in R&D. The new German tax scheme will reinforce this advantage, without any risk of European litigation, since R&D support falls under the exemptions to the European Commission’s control system on state aid. France’s comparative advantage tends to be situated in services. France’s R&D effort in services is more intense than in Germany: 0.28% of GDP in Germany and 0.67% in France. However, France stands out for providing less public support for R&D investment by service companies. In 2015, public funding’s share of private research in services was 4% in France, compared to 11% in Germany, according to an INSEE study. The “German CIR” will only increase the relative price of French private research in services in comparison with German research. However, the R&D content of services determines the price, since it determines their technological content. The German tax advantage will therefore accentuate the cost advantage of the technological services which are themselves incorporated into manufacturing value added. So this will in turn increase the cost advantage of German manufacturers.

In addition, the price of R&D is increasingly determined by personnel costs, whose share in R&D has tended to rise in Italy and France and slightly too in Germany. This share was roughly equal in the latter two countries in 2017: 61.8% in Germany, and 59.7% in France.[5] Relative changes in researchers’ salaries will have an impact on the difference in the amount of the tax credit between France and Germany. As noted, the new scheme introduced across the Rhine is based only on the costs of personnel. It could thus be conceptualized as a credit like France’s Competitiveness and Employment Tax Credit (CICE) targeted at high-skilled workers in the research sector (referring to the CICE credit before it transforms into a reduction in employer social security contributions).

This is the reason why we think that Germany has rather wanted to pursue its policy of lowering corporate taxes. This was one of the motivations for France’s CIR reform in 2008, which “[can] be viewed as [fiscal] compensation for lower corporate tax rates in other countries” (Lentile and Mairesse, 2009). The median tax rate in the OECD applied to large corporations has fallen continuously since 1995 (13 points over the period 1995-2018), from 35% to 22%. However, the German rate, which has fluctuated between 29 and 30% since 2008, is close to the French rate (around 32% in 2020; EC, 2020). The opposition that could exist in the realm of “tax philosophy”, between a French system based on a high rate and numerous provisions for exemptions, and a German system based on a broad base and low rates, is not as strong now that Germany has set up its own “CIR” credit.

This new incentive is expected to enhance Germany’s attractiveness for R&D activities, which has deteriorated somewhat (EY, 2020; see also CNEPI, 2019). Since 2011, the top three countries welcoming the most R&D centre projects were the United Kingdom, followed by Germany and France. Since 2018, France has hosted more projects than Germany (1197 against 971 in 2019), relegating Germany to third place (this had already transpired in 2009, during the financial crisis). The new tax credit should influence the trade-off of foreign companies that are hesitating between France and Germany about where to set up. It should also attract French companies to Germany, in the same way that a significant share of private R&D activities carried out in France come from foreign companies: 21% in 2015, for the percentage of expenditure as well as the percentage of employed researchers (see Salies, 2020). In accordance with European law, French companies established across the Rhine, and liable for the “Körperschaftsteuer” (German corporate tax), should be able to benefit from this niche.

Finally, private and public R&D entities located in France should be able to benefit from the tax incentive introduced in Germany, via subcontracting. But this will be only of marginal benefit, for two reasons: the tradition of the German “Mittelstand” has a culture favouring local networks, and the base for outsourced activities is capped (as with France’s CIR credit). French subcontractors will probably be able to benefit from authorizations, in the same way as France’s research ministry, the MESRI, issues authorizations in Germany. Since 2009, Germany has recovered 6% of the subcontracting approvals granted by the MESRI, the United Kingdom 4%, etc. The majority of authorizations are granted to companies located in France (75%).

Whatever the reasons that motivated the German Parliament to introduce a tax incentive in favour of R&D expenditure, it is certain that France has no interest in retiring its own scheme. This does not mean France shouldn’t reform the CIR credit, as the leverage effects are not as strong as expected; aid (direct and indirect), in GDP points, has increased on average by 5.7% per year since 2000, whereas R&D, also in GDP points, has increased only by 0.73% per year. The weak leverage effect may have been the factor that for a long time discouraged Germany from introducing a tax break to boost R&D.

In this period of searching for ways to support business, it goes without saying that the research tax credit will remain unchanged in France and could see the base for the scheme expanded in Germany (in particular to help car manufacturers who have been refused a plan for direct support).

It is nonetheless regrettable that one of the reasons for Germany’s new scheme is probably to be found in the inability of the Member States to advance the European Common Corporate Consolidated Tax Base (CCCTB) directive, which provides for harmonized R&D taxation for large firms by deducting R&D expenditure from the tax base on corporate profits. The German CIR may well be in competition with the French CIR, leading to transfers of R&D (by multinationals) from one State to another. The net increase in R&D spending by European companies remains to be estimated. Unless this spending increases, German policy could be viewed as yet one more uncooperative tax policy coming at a time when Europe is looking for common tax revenue.

[1]. The French CIR credit includes, in addition to personnel costs, costs for the acquisition of patents, standardization, allocations relating to the depreciation of buildings used for research, etc.

[2]. Based on a private R&D expenditure of 62 billion euros in 2017 (direct aid excluded), we find 0.25 (the rate of the tax credit), 0.6 (the share of salaries in R&D), yielding a credit of 9.3 billion euros.

[3]. The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Slovenia, Slovakia, Belgium, Latvia, Italy, Romania, Austria, Lithuania, Portugal, Hungary, Estonia, Cyprus, Greece, Bulgaria, Poland and Malta.

[4]. The GDP of these countries (at market prices in 2017) is 2.5 times that of Germany.

[5] The increase in France and in Italy was +7 and +20 points respectively over the period 2000-2017.

Leave a Reply