by Elliot Aurissergues, Christophe Blot and Caroline Bozou

The latest inflation figures for the United States confirm the trends seen over the last few months. In October 2021, consumer prices rose by 6.2% year-on-year. While rising prices is a global phenomenon, among the industrialized countries this has been particularly marked in the US. Inflation in the euro zone over the same period was 4.1%. This level of increase in inflation has not been seen since the late 1990s, so it is attracting considerable attention in the US policy debate, not least because it echoes a controversy that began early in Joe Biden’s mandate over the fiscal stimulus passed in March 2021. Although inflation is being driven in part by rising energy prices, the fact remains that tensions have rapidly increased. Excluding energy and food components, inflation has exceeded 4% since June 2021, suggesting a risk of overheating for the US economy. While the European macroeconomic context does not allow us to identify an equivalent risk for the euro zone, the fact remains that a sustained rise in US inflation could have repercussions for the zone. Beyond the impact on competitiveness, the dynamics of US inflation could influence decisions on rate changes and the conduct of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

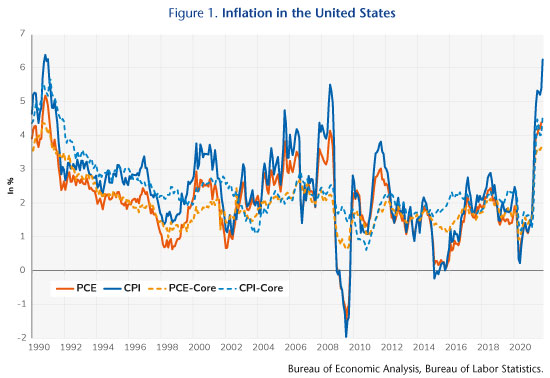

Regardless of the indicator – consumer price index or consumption deflator – prices have clearly accelerated since March 2021 (see the figure)[1]. The energy component is undoubtedly important, but it does not fully explain this dynamic, since the latest figures for the underlying indices, i.e. adjusted for energy and food prices, show a year-on-year increase of 4.6% for the CPI and 3.6% for the consumption deflator[2]. Note too that this development reflects a catch-up from 2020, when inflation was particularly moderate in the context of the pandemic and the sudden halt in activity. Thus, on average over 2020 and 2021, up to October, the consumption deflator has risen by 2.1%, in line with the target adopted by the Federal Reserve[3]. The recent tensions obviously reflect the dynamics of the post-lockdown global economic recovery, which the United States is clearly part of, and which has led to strong pressure on energy prices, but also on supplies, as evidenced by the supply difficulties for certain goods and the soaring cost of maritime freight.

Beyond these global factors, there is the question of an inflationary phenomenon that may be intrinsically linked to US economic policy. Even before the recent discussions on the 2022 budget vote, the measures taken to deal with the Covid crisis first by the Trump administration and then by the Biden administration amount to a grand total of USD 5.2 trillion, representing more than 23 points of GDP for the year 2019. This spending over 2020 and 2021 represents an unprecedented level of stimulus over the last forty years. While there was undoubtedly a consensus on the need for the measures proposed by Biden and approved by Congress in March 2021, their magnitude nevertheless caused a great deal of debate, as the recovery was already underway and the economy was already benefiting, as it still is today, from the fiscal support measures voted in 2020 and from a highly expansionary monetary policy[4]. Could this expansionary economic policy – both fiscal and monetary – be causing the economy to overheat, fuelling the return of inflation, as economists such as Lawrence Summers and Olivier Blanchard fear, or, on the contrary, is the effect on inflation being overestimated, as other analyses suggest? We plunge into this debate in an OFCE Policy Brief, specifying in particular the conditions that could lead to a sustainable increase in inflation. The risk will depend on the size of the multipliers measuring the effect of the stimulus plans on activity and unemployment, the position of the US economy relative to its potential, and changes in inflation expectations, all of which are subject to some uncertainty.

[1] The consumer price index (CPI) is calculated from a survey of the prices of a basket of average goods consumed by a representative household. The consumption deflator is derived from the national accounts and represents the price system that allows the transition from consumption in value to consumption in volume. See La désinflation importée [Imported Deflation] in OFCE Review, 2019, No. 162, for more details on the difference between these two measures of inflation.

[2] Unadjusted for energy and food prices, the consumption deflator rose by 4.4%. The data for the deflator refer to the month of September, while the publication of the consumer price indices is more rapid, the latest figures published being those for October.

[3] The consumer price deflator is the indicator used by the Federal Reserve to assess price stability in the United States.

[4] Two other projects were then announced: an infrastructure investment plan (American Jobs Plan) and a household package (American Families Plan). These are not crisis-specific measures, but measures that are supposed to mark the direction of fiscal policy over the next eight years. These plans are currently being discussed in Congress as part of the 2022 budget vote.