With the return of inflation in 2021, the focus is now on the central banks and their mandate for price stability. Between 15 and 17 December 2021, the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England (BoE), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) all held their final monetary policy meetings of 2021. What do these meetings tell us about their approaches to asset purchases and monetary policy in 2022? Is a rapid rise in interest rates on the cards? Despite remaining uncertainty about the future course of the pandemic and its consequences for activity in the first half of 2022, the central banks have gradually revised their assessment of the situation with regard to rising inflation. They now think that the inflationary shock will continue into 2022. Based on this, the British were the first to act as the BoE announced an increase in its key rate. The Federal Reserve is likely to follow in 2022, presaging future normalization. As for the ECB, despite winding down its asset purchase programme linked to the health crisis, it is not yet envisaging the normalization of monetary policy. In any event, its latest meeting did not suggest a rate hike in 2022 in the euro zone.

Central banks raise inflation expectations

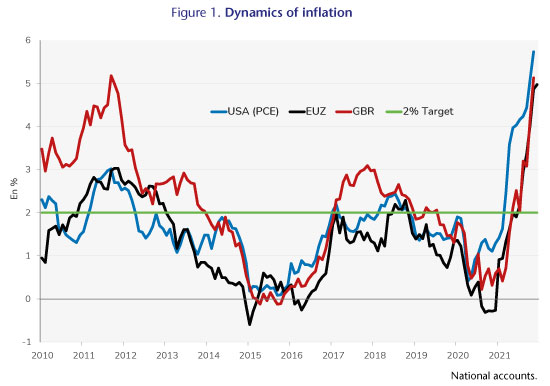

The recent surge in prices in all the industrialized and emerging countries is largely due to the rebound in energy and many other commodity prices in connection with the effects of the health crisis on the global economic situation in 2020 and 2021.[1] This follows a long period of low inflation, which led central banks to set their interest rates at a very low level and to implement unconventional monetary policies such as asset purchase programmes. These policies, which resulted in sharp increases in their balance sheets, were aimed at holding down long-term rates.[2] Yet price stability is a key element of the central banks’ mandate. It is therefore natural that the recent inflationary pressures raise the question of how they will react and whether they might tighten their monetary policy stance, since inflation is well above the 2% target generally used by central banks to judge price stability.[3] Indeed, in December 2021, the year-on-year change in the consumer price index rose to 5% in the euro zone and, in November, 5.1% in the UK (Figure 1). In the United States, the consumer price deflator – an indicator monitored by the Federal Reserve – rose by 5.7%, the highest level since the early 1980s.[4] Beyond the impact on energy prices, the underlying indices also rose. In the euro zone, the year-on-year change climbed from 0.4% in December 2020 to 2.7% a year later, while in the US the underlying consumption deflator reached 4.7% in November.[5]

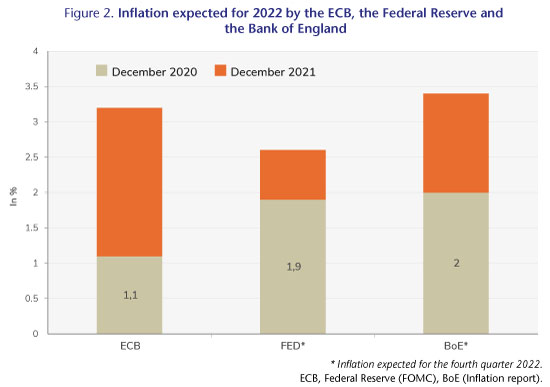

While initially the central banks were not all that concerned about the phenomenon, considering it temporary, it is clear that they have gradually revised their view, resulting in upward revisions of their inflation expectations for 2022 (Figure 2). Thus, the inflation projection that was communicated by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in December 2020 for the end of 2022 was 1.9%. One year later, the inflation forecast for the fourth quarter of 2022 was 2.6%. The ECB has also issued a significant revision, with inflation expectations rising from 1.1% in December 2020 to 3.2% – for the year as a whole – according to the latest projections of December 2021.[6] Inflationary pressure is still considered temporary, as all three central banks foresee inflation in 2023 closer to the target.[7] Nevertheless, in the context of a recovery but also of uncertainty about the effects of the new Omicron variant, the central banks are facing a dilemma. Should they counter these inflationary pressures by tightening monetary policy? Even if the rebound in inflation is temporary, inflation would be well above target for some months, which could lead to second-round effects. Moreover, the accumulation of household savings could boost growth in 2022 and keep inflation high.[8]

Conversely, could tightening prematurely undermine the recovery and slow the fall in the unemployment rate? In this respect, the unexpected return of inflation could also provide an opportunity to see how the ECB and the Federal Reserve might adjust their monetary policy after the announcement of their inflation target revisions. Indeed, in July 2020, the US central bank announced that it wished to wait for an inflation target of 2% on average, indicating that after being under target, as was the case in recent years, it would tolerate inflation above 2%. The rebound in inflation might have suggested that the Federal Reserve would be less reactive to rising inflation. However, the acceleration of prices has been significant in the US, and the recent change in tone suggests that even if the Fed tolerates inflation above 2%, the current level is probably too high.[9] Paradoxically, the ECB has not announced average inflation targeting (AIT) but has made it clear that the target is 2% and that it should be interpreted symmetrically. The ECB therefore considers that inflation below or above 2% is not compatible with its objective of price stability. Nevertheless, this is a medium-term target and takes into account lags in the transmission of monetary policy. So even though the ECB has not indicated that it will tolerate inflation above 2%, it will not automatically tighten monetary policy when observed inflation exceeds the target but it will condition its action on its inflation expectations over a 12 to 24-month horizon. Its expectation for 2023 therefore indicates that current inflation is temporary and that beyond 2022 inflation should again be below 2%.

The Bank of England and Federal Reserve consider normalization

The communications from the central banks’ monetary policy meetings held between 15 and 17 December 2021 were expected to focus on two points: the continuation of their asset purchase programmes and the level of the key interest rates.

The BoE was the quickest to react by raising its key rate by 0.15 percentage points, from 0.1% to 0.25%. As stated in its 16 December press release: “The MPC’s remit is clear that the inflation target applies at all times, reflecting the primacy of price stability in the UK monetary policy framework.” Furthermore, it was decided to maintain the stock of securities acquired by the BoE. A key element of this decision is the way in which the BoE has implemented its asset purchase policy. Unlike the Federal Reserve and the ECB, which announce purchase flows on a monthly basis, the BoE proceeds in stages, announcing a target for the stock of assets – revised if necessary – and making purchases quickly in order to reach the target.[10] Moreover, the BoE has not made its rate decisions conditional on its asset purchase policy, whereas ECB communiqués have always stated that it would only consider rate hikes once asset purchases have stopped.

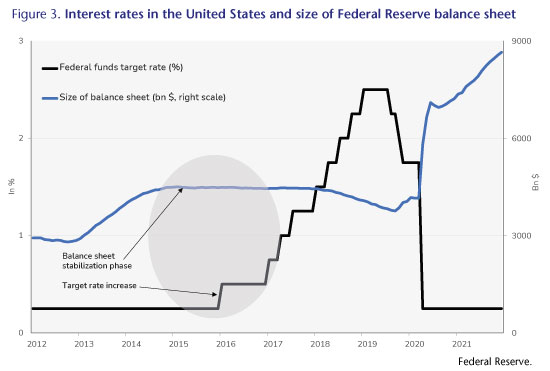

In the United States, a rate hike is to be preceded by a so-called taperingphase during which the Federal Reserve gradually reduces monthly purchases. The strategy implemented by the US central bank therefore consists first of all of communicating this path for asset purchases. This first step was launched in November. At the meeting of 15 December 2021, the FOMC announced that the pace of tapering down was being accelerated: from January 2022, monthly purchases will be USD 60 billion (40 bn for Treasuriesand 20 bn for Mortgage-backed Securities) compared with USD 120 billion per month before November 2021. There will be further reductions in the following months. The Federal Reserve is acting in a sequenced manner, as it did during the previous phase of normalization that began in January 2014 (Figure 3). Purchases stopped at the end of 2014, and the policy rate was raised in December 2015. Finally, the reduction in the size of the balance sheet – in billions of dollars – had been announced in June 2017 and implemented from October 2017.[11] However, the timetable is likely to be accelerated, as information from the 15 December meeting suggests that there could be three rate hikes in 2022. The time between the end of asset purchases and a rate hike would be shortened, and rates would rise more quickly than in this previous phase of normalization, when there was only one hike in 2015 and another one a year later. The FOMC members in fact anticipate a target rate for federal funds of 0.9% at the end of 2022, compared to the current range of 0-0.25%.[12]

It should also be noted that, in accordance with its mandate, the FOMC is focusing on the situation in the labour market, since the Federal Reserve must not only ensure price stability but also achieve maximum employment. In this regard, while the unemployment rate fell to 4.2% in December, employment remains 1.8% (or 2.8 million jobs) below the December 2019 level, also reflecting withdrawals from the labour force. The prospects of stabilizing the size of the balance sheet – in value terms – in early 2022 and of several rate hikes therefore indicate that the Federal Reserve sees labour market conditions as gradually converging towards the maximum level of employment.

The ECB takes a more cautious approach

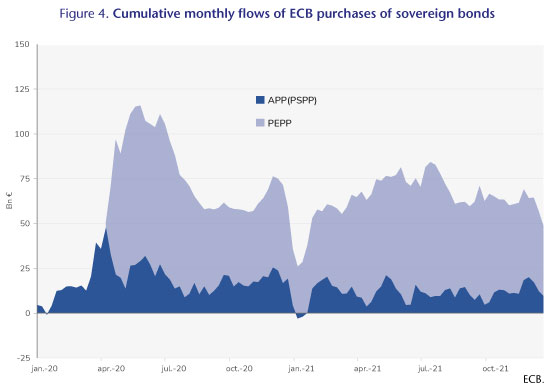

In the euro zone, inflationary pressures have increased even as the economic recovery remains more fragile. In the third quarter of 2021, GDP was still 0.3% below its level at the end of 2019, whereas for the United States it was 1.4% above. There is nevertheless improvement in terms of the unemployment rate, which in November 2021 stood at 7.3%, lower than the level observed prior to the outbreak of the pandemic. However, in her press release at the 16 November press conference, Christine Lagarde considered that monetary policy must remain accommodating in order to bring inflation down towards its medium-term target. Thus, beyond the current inflationary pressure, the ECB still considers that inflation will remain below target in 2023, which therefore argues for a slower normalization of monetary policy in the euro area. Nevertheless, the Governing Council announced the end of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) in 2022. The PEPP had been put in place in March 2020, in the context of the pandemic, to combat sovereign risk.[13] Note that purchases had already slowed in line with the announcements made since September 2021 (Figure 4). However, this reduction in purchases under the PEPP would be partly offset by an increase in purchases throughthe Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP). In the second quarter of 2022, purchases are to increase from 20 to 40 billion euros per month. They would then adjust to 20 billion euros in October 2022, after a plateau of 30 billion euros in the third quarter. At this stage, the ECB is not indicating a complete halt to asset purchases. The size of its balance sheet would therefore continue to grow, postponing for the time being the prospect of a rate hike, probably beyond 2022.[14]

Although there has been talk of normalizing monetary policy, the central banks remain cautious about the recent inflationary surge, considering it a temporary episode. The same caution seems to prevail in most other industrialized countries. In Japan, although inflation is rising (to 0.6% in December 2021), it remains well below the BoJ’s target. The BoJ has therefore not changed its communications. Quantitative easing continues, and it is sticking to the goal of keeping the short-term rate at -0.1% and the government bond rate at 0%. Earlier this month, the Bank of Canada and the Australian central bank also maintained their rate targets. The target rose, however, in Norway.

How did the markets react to these policy announcements?

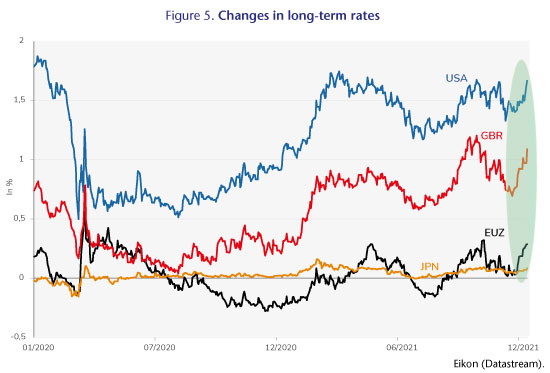

Since 15 December, long-term rates have risen in the euro zone, the United States and the United Kingdom, approaching the levels seen before the outbreak of the pandemic (Figure 5). The trend in Japan is much more modest. The average rate on government bonds issued in the euro zone rose by 24 basis points, with a slightly larger increase in Italy and Spain than in Germany and France. In the United States, the increase is comparable: 24 basis points between 14 December 2021 and 4 January 2022; but the rate is still below its pre-crisis level. In the UK, it’s risen over 35 basis points. The markets have therefore incorporated a moderate tightening of monetary policy by 2022. Should inflation remain at the level observed at the end of 2021, the central banks could accelerate the pace of monetary policy normalization, either byraising policy rates further or by reducing the size of their balance sheets, which would probably result in a further rise in long-term rates.

The year 2022 should therefore be characterized by a rise in short-term rates and probably also in long-term rates in the UK and the US. It is clear that the inflationary surge observed since mid-2021 will lead the central banks, in particular the BoE and the Federal Reserve, to accelerate the normalization process. Normalization is also important to give central banks room to manoeuvre in case of new negative shocks. There is, nevertheless, economic uncertainty due to the arrival of the Omicron variant. Even if agents have partly adapted to the health restrictions, a slowdown in growth without a reduction in inflationary pressures would create a more delicate trade-off for the central banks between their price stability objective and the need to support the economy.

[1] See the OFCE post of 17 December 2021 [in French] on this point and the more detailed analysis of Le Bayon and Péléraux (2021).

[2] The policy rate set by the central banks represents a target for very short-term market rates. Changes in this rate are then intended to influence bank rates and all market rates along the term structure.

[3] The Federal Reserve and the ECB have recently reaffirmed the symmetry of this objective by revising their inflation targets.

[4] Inflation measured by the consumer price index rose by 7.1% in December.

[5] In December 2021, the consumer price index adjusted for food and energy prices rose by 5.5%.

[6] The way that inflation expectations are determined differs between the central banks. In the case of the Federal Reserve, expectations are formulated by the members of the FOMC, while for the ECB they are formulated by its own economists.

[7] Respectively, 2.3% and 2.2% at the end of the year in the US and UK, and 1.8% for the year as a whole in the euro zone.

[8] See our October 2021 economic forecasts published in Policy Brief no. 94: Le prix de la reprise [The Price of the Recovery].

[9] See the OFCE post of 4 January 2022 on inflation targets and expectations [in French] and the detailed analysis of Blot, Bozou and Hubert (2021).

[10] See Gagnon and Sack (2018) for a comparison of these two strategies.

[11] Measured in GDP points, the size of the balance sheet fell slightly earlier, from 26.4% in Q1 2015 to 18.8% in Q2 2019. Prior to the implementation of unconventional measures, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet was between 6% and 7% of GDP.

[12] This is the scenario that emerges from the Minutes. The Federal Reserve publishes a detailed report of the FOMC meeting three weeks following the meeting.

[13] See Blot, Bozou, Creel and Hubert (2021) for a more in-depth discussion of the objectives and effects of the ECB’s sovereign asset purchase programmes.

[14] The 16 December press release does indeed state that: “We expect net purchases to end shortly before we start raising the key ECB interest rates.”