In the preamble to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, the Heads of State and Government declare that they are “[r]esolved to ensure the economic and social progress of their countries by common action to eliminate the barriers which divide Europe”. Article 117 adds that “Member States agree upon the need to promote improved working conditions and an improved standard of living for workers, so as to make possible their harmonisation while the improvement is being maintained”. Sixty years after the Treaty of Rome, what is the state of economic and social inequality in Europe? How did this change during the crisis?

Every year Eurostat measures inequality in the different EU Member States. The Great Recession has led to widening inequality within the countries of Europe. The Gini index of equivalent disposable income rose from 30.6 in 2007 to 31 in 2015 on average in the 28 EU Member States. However, part of the increase is due to large breaks in the series in France and Spain in 2008. Inequality is thus clearly lower in Europe than in the United States: for 2014, the Gini index of disposable income is estimated at 39.4 in the United States, while in the European Union it ranges from 25 (Czech Republic) to 37 (Bulgaria). The United States is therefore more unequal than any country in the EU and much more unequal than most countries.

However, the presentation of an average Gini index in the European Union may be misleading. Indeed, it takes into account only inequalities within the European countries and not inequalities between countries. However, there are significant inequalities between European countries. In the national accounts, household income based on EU consumer purchasing power in 2013 ranged from 37% of the European average (Bulgaria) to 138% (Germany), i.e. a ratio of 1 to 4.

At the European level, Eurostat calculates an average of national inequalities, as well as the international inequalities. On the other hand, Eurostat does not calculate inequalities between European citizens: what would inequality be if national barriers were eliminated and European inequality was calculated at the European level in the same way that one calculates inequality within each nation? It might seem legitimate to calculate inequality between European citizens like this insofar as the European Union constitutes a political community with its own institutions (Parliament, executive, etc.).

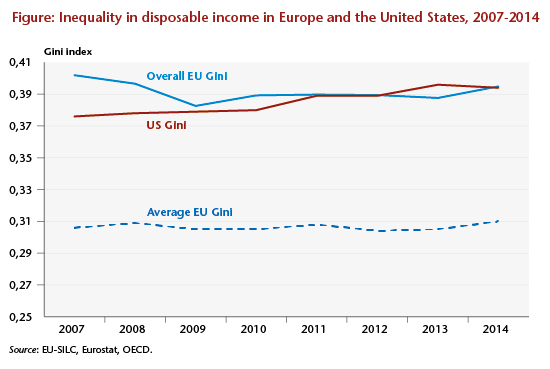

The EU-SILC database, which provides the equivalent disposable income (in purchasing power parity) of a representative sample of households in each European country makes such a calculation possible. The result is that the overall level of inequality in 2014 in the European Union is the same as that in the United States (graph). What conclusion should be drawn? If we look at the glass as half-empty, we could emphasize that European inequality is at the same level as in the world’s most unequal developed country. If we look at the glass as half-full, we could emphasize that the European Union does not constitute a nation with social and fiscal transfers, that it has recently expanded to include much poorer countries and that, nevertheless, inequality is no greater than in the United States.

Overall inequality in the European Union can be seen to decline slightly between 2007 and 2014. The Theil index, another indicator of inequality, can be used to break down the change in European inequalities between what comes from changes in inequality between countries and what comes from changes within countries. Between 2007 and 2014, the Theil index fell from 0.228 to 0.214 (-0.014). Inequality within countries was generally stable (+0.001) whereas inequality between countries declined (-0.015). These developments are similar to what has been observed by Lakner and Milanovic at the global level (“Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Wall to the Great Recession“): rising national inequalities and declining inequalities between countries (in particular due to China and India catching up).

So far, the main instrument used by the European Union to reduce inequality in Europe has been the opening of borders. But while opening up borders can help the EU’s less affluent countries (notably Bulgaria and Poland) to catch up, it can also have an impact on inequality within countries. However, Europe does not as yet have a social policy. This sphere falls above all within the competence of the States. But opening up the borders is exacerbating social and fiscal competition. For instance, the higher marginal rates of personal income tax (IRPP) and corporate income tax (IS) have dropped significantly since the mid-1990s, while the VAT rate has increased (A.Bénassy-Quéré et al., “Reinforcing tax harmonization in Europe” [in French]).

In France, the government has committed to lower the corporate income tax rate from 33.3% to 28% by 2020. This follows a trend towards lowering taxation on business but raising it on households. The impact on inequality has so far been counterbalanced by the fact that the rise in taxation has focused on the wealthiest households. However, the French Presidential candidates Fillon and Macron advocate a substantial reduction in the taxation of capital income (withholding tax and the reduction of the ISF wealth tax on real estate for Macron; elimination of the wealth tax for Fillon) in the name of competitiveness. The dangers of fiscal and social competition are thus beginning to make themselves felt.

Leave a Reply