Christophe Blot and Francesco Saraceno

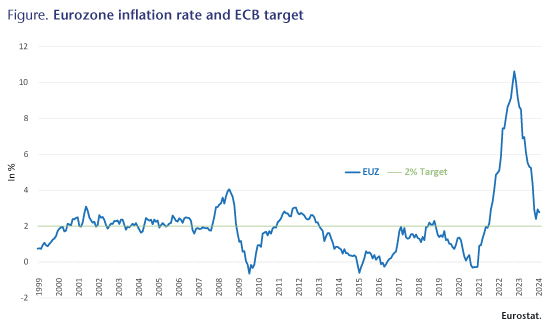

The inflation rate in the Eurozone continues to decline. In February, it dropped to 2.6%, more than two percentage points lower than the August figure (See Figure). The inflation rate is still above the ECB 2% inflation target despite the monetary policy tightening implemented since Summer 2022. Since then, the deposit facility rate has increased from -0,5 % to 4 %. Over the past year, the reduction in inflation has been largely due to the disappearance of the factors that had fueled the inflationary spike in the first place (bottlenecks, energy, post-pandemic recovery), which no longer have a significant impact today. There is indeed a broad consensus among economists that monetary policies take several quarters to influence demand, growth, and price dynamics[1]. Therefore, the tightening started to be felt only in 2023, and the peak is still to be reached. Rising interest rates are starting to weigh on consumption, investment, and public spending, contributing to the decline in inflation through a cooling of aggregate demand. It may be noticed that the current situation contrasts with the pre-Covid period where inflation remained below the target for a sustained period despite the expansionary measures – and notably unconventional ones – introduced by the ECB. Such difficulty in reaching the inflation target raises the issue of the appropriate numerical value for the target. Is the current 2% figure too high or too low?

According to the latest forecasts of the Eurosystem staff, inflation would still remain above the 2% target in 2024 (2.7%) and would not be in line with the target before 2025 The slow convergence to the target and the economic slowdown would lead the ECB to stop tightening monetary policy but no interest rate cuts have been contemplated so far (even if markets expect one in the next few months)[2]. Nevertheless, in spite of the high uncertainty surrounding economic activity and inflation, the overall consensus of forecasters is that the inflation episode is largely behind us. Therefore, it is time to start drawing lessons not only from the recent increase in prices but also from the previous long period, between the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and 2019 when the ECB faced the opposite problem, unsuccessfully trying to raise an inflation rate that remained stubbornly close to deflation.

A meaningful discussion on the central banks’ objectives would have been unwarranted while inflation was not under control. They would have been accused of shifting the goalposts. However, once their credibility is preserved by demonstrating that they have been able whatever it takes to bring inflation back to close to 2%, central banks should take stock of the recent experiences with inflation and with deflation and proceed with a review of their objectives.

Drawing lessons from multiple crises

Some economists, including Nobel laureate Paul Krugman and former IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard, argue that the central banks of advanced economies should reconsider the inflation target, raising it from 2% to 3%[3]. It is worth noting that the 2% inflation target, introduced in New Zealand in 1980 and subsequently adopted by nearly all major central banks (and notably the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan), has no particular basis; it was simply believed, when adopted, to be low enough to reassure the markets about price stability and minimize the economic cost of inflation, while allowing for some margin for adjustment: in the event of negative shocks, inflation could fall without going into negative territory and triggering dangerous deflationary spirals.

There are essentially two arguments in favor of increasing the desired inflation target. The first is contingent: while inflation has dropped relatively painlessly from double-digit levels a year ago to values close to the target today, bringing it from the current level to 2% may prove much more difficult. We could remain stuck with inflation rates fluctuating between 2% and 3%, or even slightly higher. These levels do not create significant instability problems (in terms of de-anchoring expectations, for example), so it may not be worth paying the price in terms of growth and unemployment of forcing inflation to return to 2%.

The second reason for a revision of the desired inflation rate is more structural. The 2% target may have seemed reasonable during the long period of the Great Moderation when stable (though not stellar) GDP growth was accompanied by limited fluctuations in the inflation rate. However, that period of apparent macroeconomic stability concealed growing imbalances, such as a chronic tendency toward excess savings and, consequently, increasingly lower equilibrium (“neutral”) real interest rates[4].

Since 2008, we have entered a new phase where imbalances have come to light, and macroeconomic shocks have become more severe. In a context of greater instability, central banks may find themselves in need of significantly reducing interest rates. If these rates are initially moderate, the risk of hitting what economists call the effective lower bound (interest rates that cannot be lowered below zero or slightly negative values) increases. This is the situation in which the Fed and the ECB have found themselves for the whole decade of the 2010s, having to resort to unconventional policies such as asset purchases to stimulate the economy. A higher inflation target would allow for higher interest rates under normal conditions and more room to lower them when necessary. This additional margin could prove valuable in the likely event that the coming years bring increased macroeconomic and geopolitical instabilities. Andrade et al. (2021) for instance show that while a 1.4% inflation target was consistent with a pre-crisis estimation of the short-term interest rate that would prevail when the inflation rate is stable and the economy at full employment (r-star) of 2.8%, a one-point decrease of r-star should lead the central bank to revise upward its inflation target by 0.8 point[5]. According to the revised estimates of Holston, Laubach and Williams (2023), the current r-star in the Eurozone would be negative (-0.7%) entailing an optimal target at 2.8%.

Furthermore, structural factors such as the ecological transition could lead to structurally higher inflation rates in the coming years, e.g., due to higher costs associated with fossil fuels (notice though, that some argue instead that secular stagnation might not be over). Insisting on aiming for 2% inflation could require long periods of monetary tightening, hindering investment in renewables and paradoxically perpetuating the inflationary tensions related to the transition.

To these reasonable arguments in favor of a higher inflation target, those against revising it oppose equally reasonable ones. The most significant one is that, in a world like that of central banks, where credibility is everything, changing the inflation target in the process of bringing inflation down could be devastating, essentially a confession of impotence: shifting the goalposts during the game. Moreover, how credible can a central bank be that announces a 3% inflation target when, between 2008 and 2020, it was unable to move from 1% to 2%? Another argument, recently made by Martin Wolf concerning the UK, is that central banks have an implicit bias, being more reluctant to tighten when inflation increases than to loosen when it drops. This leads to an overall level of inflation somewhat higher than the target and makes calls for higher targets dangerous. This argument hardly seems to apply to the current situation. If anything, the experience of the 25 years of existence of the euro points to a deflationary bias.

The solution, therefore, seems to be only one. For this round of the merry-go-round, unfortunately, there is little to be done, and we must resign ourselves to paying the costs of central banks’ ill-advised commitment to an inflation target of 2% through a monetary restriction, instead of resorting to a more multitool policy mix. Governments and fiscal policies should be prepared to mitigate these costs with income policies and fiscal redistribution to protect the most vulnerable economic agents.

Do central banks control inflation precisely?

This discussion should not overlook the question of the ability of the ECB to control inflation. The recent surge of inflation and the difficult task for central banks to bring it back to 2% echoes the already mentioned difficulties of the same central banks to increase inflation to 2% when it was persistently low during the last decade. Many have argued from the outset of the current inflationary episode that addressing inflation with monetary tightening was the wrong approach (here, or there); other, more targeted, microeconomic tools would have been more effective (among other things because monetary policy is characterized by long lags) and less painful for addressing a structural inflation resulting from sectoral imbalances rather than from generalized overheating. However, whether due to the inertia of governments, as usual happy to delegate unpopular decisions to the ECB, or to the old monetarist reflexes, which, although minoritarian in academia unfortunately remain influential in public debate (“inflation is always caused by too much money chasing too few goods”), central banks have been the main characters in the fight against inflation.

Said it differently, demand and supply, micro and macro elements interact, in determining an average inflation rate that has multiple causes. Inflation and deflation are complex phenomena that are better tackled with a plurality of instruments and monetary policy alone may not be powerful enough. This may have two implications. First, coordination of monetary and fiscal policies may help to better achieve the target. Second, if the central is not all-powerful in fighting a phenomenon that depends on other causes, it may be more reasonable not to target a point of inflation but a target zone.

Announcing a range is certainly more realistic as central banks cannot reach the 2% with complete precision. There are always many sources of uncertainty related to the effectiveness of monetary policy, its transmission delays, future shocks, the relation between activity and prices (the slope of the Phillips curve). Furthermore, the measure of inflation relies on some ad-hoc indicators and is inevitably subject to measurement errors, which may stem from the breakdown of quality and price effects, the inclusion of all the dimensions of the cost of life, which are not accounted for by a point target.

These uncertainties affect inflation and may eventually challenge the central bank’s credibility. Finally, a range would also provide the ECB with more leeway to handle tradeoffs between its objectives. Of course, a criticism against a target range is that it is less precise, which could undermine its credibility[6]. But the credibility argument can be used in the other direction. How credible is a central bank that systematically misses its very specific target?

[1] See OFCE Blog for a brief review.

[2] In the press conference, following the 25 January Governing Council, Christine Lagarde stated that “it was premature to discuss rate cuts”.

[3] It is useful to remind that the 2% target for the inflation rate has been adopted by several of central banks and notably the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan.

[4] See Chapter 2 from the April 2023 IMF World economic outlook.

[5] See Andrade, P., Galí, J., Le Bihan, H., & Matheron, J. (2021). Should the ECB adjust its strategy in the face of a lower r★?. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 132, 104207.

[6] Ehrmann (2021) shows that inflation anchoring is not reduced in countries which have target zones but conversely that credibility is improved. See “Point targets, tolerance bands or target ranges? Inflation target types and the anchoring of inflation expectations.” Journal of International Economics, 132, 103514.