The impact on redistribution of the ECB’s monetary policy

By Jérôme Creel and Mehdi El Herradi

A few weeks before Christine Lagarde assumes the

presidency of the European Central Bank (ECB), it may be useful to examine the

balance sheet of her predecessors, not only on macroeconomic and financial

matters but also with respect to inequality. In recent years, the problem of

the redistributive effects of monetary policy has become an important issue,

both academically and at the level of economic policy discussions.

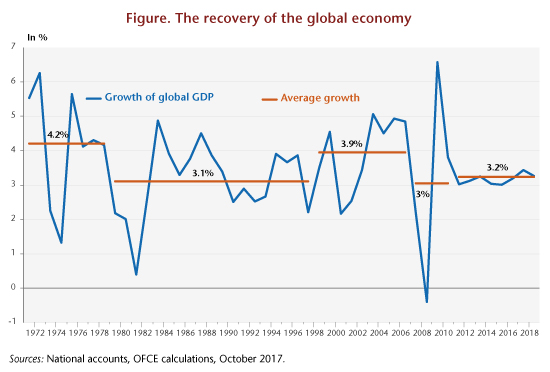

Interest in this subject has grown in a context

marked by the conjunction of two factors. First there has been a persistent

level of inequality in wealth and income, which has been hard to reduce. Then there are the activities

of the central banks in the advanced economies following the 2008 crisis to

support growth, particularly through the implementation of so-called “unconventional”

measures [1]. These measures, mainly manifested in quantitative

easing (QE) programmes, are suspected to have increased the prices of financial

assets and, as a result, favoured wealthier households. At the same time, the

low interest rate policy could have resulted in a reduction in interest income

on assets with fixed yields, most of which are held by low-income households. On

the other hand, the real effects of monetary policy, particularly on changes in

the unemployment rate, could help keep low-income households in employment. The

ensuing debate, which initially broke out in the United States, also erupted at

the level of the euro

zone after the ECB launched

its QE programme.

In a recent

study focusing on 10 euro zone

countries between 2000 and 2015, we analysed the impact of the ECB’s monetary

policy measures – both conventional and unconventional – on income inequality. To

do this, we drew on three key indicators: the Gini coefficient, both before and

after redistribution, and an interdecile ratio (the ratio between the richest

20% and the poorest 20%).

Three main results emerge from our study. On the

one hand, a restrictive monetary policy has a modest impact on income

inequality, regardless of the indicator of inequality used. On the other hand,

this effect is mainly due to the southern European countries, especially in the

period of conventional monetary policy. Finally, we found that the

redistributive effects of conventional and unconventional monetary policies do

not differ significantly.

These results thus suggest that the monetary

policies pursued by the ECB since the crisis have probably had an insignificant

and possibly even favourable impact on income inequality. The forthcoming

normalization of the euro zone’s monetary policy could, on the contrary,

increase inequality. Although this increase may be limited, it is important

that decision-makers anticipate it.

[1] For an analysis of the expected impact of the

ECB’s unconventional policies, see Blot et al. (2015).