Flexibility versus the new fiscal effort – the last word has not been spoken

By Raul Sampognaro

On 13 January, the Juncker Commission clarified its position on the flexibility that the Member States have in implementing the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). The new reading of the SGP should result in reining in the fiscal consolidation required for certain countries[1]. Henceforth, the Commission can apply the “structural reform clause” to a country in the corrective arm of the Pact[2], whereas previously this was only possible for countries in the Pact’s preventive arm[3]. This clause will allow a Member State to deviate temporarily from its prior commitments and postpone them to a time when the fruits of reform would make adjustment easier. In order for the Commission to agree to activate the clause, certain conditions must be met:

– The reform plan submitted by the Member State must be major and detailed, and approved by the Government or the National Parliament; its timetable for implementation must be explicit and credible;

– The plan must have a favourable impact on potential growth and / or the public finances in the medium-term. The quantification of the impact should be carried out transparently and the Member State must submit the relevant documentation to the Commission;

– The Member State must make a structural budget improvement of at least 0.5 GDP point.

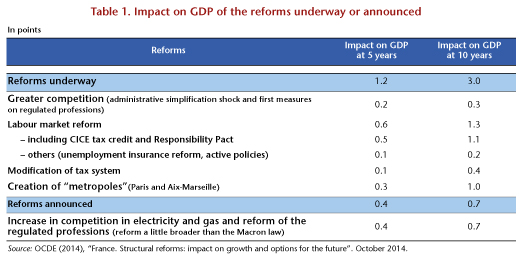

In this new context, France has reforms it can point to, such as the regional reform and the law on growth and activity, the so-called Macron law. According to OECD calculations from October 2014, the reforms already underway or being adopted [4] could boost GDP by 1.6 points over the next 5 years while improving the structural budget balance by 0.8 GDP point[5] (the details of the impacts estimated by the OECD are shown in Table 1).

In March, the Commission will decide whether France’s 2015 Finance Act complies with the rules of the SGP. To benefit from the structural reform clause, France must then meet certain conditions:

1) The outline of the reforms needs to be clarified: at end December 2014, the Commission felt that there were still many lingering uncertainties concerning the regional reform and the content of the Macron law, uncertainties that will be resolved in the course of the parliamentary process.

2) The Ministry of Finance at Bercy must produce credible assessments of the impact of the Macron law, while the Commission will carry out its own evaluation. The Commission has already noted that the OECD’s calculations will constitute the upper bound of the impact.

The evaluation of the 2015 Finance Act may result in the imposition of financial sanctions on France, unless the government decides to go for a greater fiscal adjustment. The Commission warned in late November that further steps would be needed to ensure that the 2015 budget complies with the SGP. Indeed, the Commission found that the adjustment was only 0.3 GDP point, while in June 2013 France had committed to an annual structural adjustment of 0.8 point in 2015 to bring its deficit below 3% in 2015[6].

While the Commission approves the positive effects expected from the reforms, there is a problem with the application of the “structural reform clause”: the structural budgetary adjustment is still below 0.5 GDP point, which prevents the application of the new clause. France therefore still faces the threat of sanctions, despite the new doctrine.

While this analysis of the document published on January 13 shows that the Commission has given the Pact greater flexibility, it also shows that the Commission expects France to make a larger fiscal adjustment. This would be on the order of 4 billion euros (0.2 percent of French GDP) instead of the 8 billion (0.4 percent of GDP) that would have been expected back in October (the impact of a strict reading of the Pact has been analyzed here).

The Government’s refrain is that it does not wish to go any further with fiscal adjustment, that this is not desirable in the current economic climate: 2015 could be a year for recovery provided that the risk of deflation is taken seriously. There is a lot of support for economic activity, including lower prices for oil and the euro, an expansionary monetary policy and the Juncker plan, even if the latter needed to go much further. However, France’s fiscal policy is continuing to be a drag, and just how much so will remain uncertain until March. From now till then, with the terms of the debate clearly spelled out, everyone will need to take the risk of deflation seriously.

[1] The Commission permits subtracting investments made under the Juncker Commission Plan from the deficit calculation; it clarifies the applicability of the “structural reform clause” and moderates the speed of convergence towards the medium term objectives (MTO) for countries in the preventive arm of the Pact based on their position in the business cycle.

[2]Grosso modo this means countries with a deficit of more than 3%.

[3]Grosso modo this means countries with a deficit of less than 3%.

[4] Which goes beyond the Macron law alone and includes the CICE tax credit and the Responsibility Pact.

[5] The OECD data were used by the Prime Minister in his October 27 letter to the Commission.

[6] In its 2014 autumn forecast, the Commission quantified the adjustment at 0.1 GDP point, but this figure is not directly comparable with the commitment of 0.8 point from June 2013. Once the changes in national accounting standards and the unpredictable changes in certain variables are taken into account, the corrected adjustment is 0.3 GDP point. This figure is the calculation basis for the excessive deficit procedure.