By Céline Antonin and Sandrine Levasseur

For two weeks Cyprus sent tremors through the European Union. If the banking crisis that the island is going through has attracted much attention, it is essentially for two reasons. First, because the dithering over the rescue plan led to a crisis of confidence in deposit insurance, and second, because it was the first time that the European Union had allowed a bank to fail without coming to its aid. While the method of resolving the Cyprus crisis seems to represent an institutional advance [1], insofar as investors have been forced to face up to their responsibilities and citizens no longer have to pay for the mistakes of the banks, the impact of the purge of the island’s real economy will nevertheless be massive. With its heavy dependence on the banking and financial sector, Cyprus is likely to face a severe recession and will have to reinvent a growth model in the years to come. In this respect, the exploitation of natural gas resources seems an interesting prospect that should not be ruled out in the medium / long term.

To grasp what is at stake in Cyprus today, let us briefly recall the facts. On 25 June 2012, Cyprus requested financial assistance from the EU and the IMF, essentially in order to bail out its two main banks (Laiki Bank and Bank of Cyprus), whose losses are estimated at 4.5 billion euros due to their high exposure to Greece. Cypriot banks were hit both by the depreciation of the Greek assets they held on their balance sheets and by the partial write-down of Greek debt under the second bail-out plan (PSI Plan of March 2012 [2]). Cyprus estimated that it needed 17 billion euros in total over four years to prop up its economy and its banks, about one year of the island’s GDP (17.9 billion euros in 2012). But its backers were not ready to give it this much: the national debt, which had already reached 71.1% of GDP in 2011, would become unsustainable. The IMF and the euro zone thus came to an agreement on a smaller loan, with a maximum amount of 10 billion euros (9 billion financed by the euro zone and 1 billion by the IMF) to recapitalize the Cypriot banks and finance the island’s budget for three years. Cyprus was in turn ordered to find the remaining 7 billion through various reforms: privatizations, an increase in corporate tax from 10 to 12.5%, and a windfall tax on bank deposits.

Initially [3], Nicosia decided to introduce a one-off tax of 6.75% on deposits of between 20,000 and 100,000 euros and 9.9% on those above 100,000 euros, and a withholding tax on interest on these deposits. Given the magnitude of the resulting protest, the government revised its approach, and the taxation of deposits gave way to a bankruptcy and restructuring. The solution adopted concerned the country’s two main banks, Laïki Bank and Bank of Cyprus. Laïki was closed and split into two: first, a “good bank” that will take over the insured deposits (less than 100,000 euros) and the loans from the ECB to Laïki [4], but which will also take over its assets and ultimately be absorbed by Bank of Cyprus; and second, a “bad bank” that will accommodate the stocks, bonds, unsecured deposits (above 100,000 euros), and which will be used to pay off Laïki‘s debts [4], according to the order of priority associated with bank liquidations (depositors being paid first). In addition to absorbing the “good bank” hived off of Laïki, Bank of Cyprus will freeze its unsecured deposits, some of which will be converted into shares to be used in its recapitalization. To prevent a flight of deposits, temporary [5] capital controls were put in place.

This plan introduces a paradigm shift in the method of resolving banking crises in the European Union. At the beginning of the euro zone crisis, in particular in the emblematic case of Ireland, the European Union considered that creditors had to be spared in the event of losses, under the logic of “too big to fail”, and it called on the European taxpayer. But in 2012, even before the declaration of Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Europe’s doctrine had already begun to bend [6]. Hence, on 6 June 2012, the European Commission proposed a Directive on the reorganization and resolution of failing credit institutions, which provided for calling on shareholders and bondholders to contribute. [7] However, the rules on creditors are to apply only from 2018, after approval of the text by the Council and the European Parliament. This type of approach is now being tested experimentally in the Cyprus crisis.

Heavy consequences for the real economy

The situation of the country before 2008

In the period preceding the global economic crisis, the Cypriot economy was thriving, and indeed in 2007 even in danger of overheating. Over the period 2000-2006, its GDP grew on average by 3.6% per year, with growth of 5.1% in 2007. The unemployment rate was low (4.2% in 2007), with even some labour shortage as a result of the emigration of Cypriot nationals to other EU countries. The influx of foreign workers into Cyprus helped to hold down wages. Consumer spending and, to an even greater extent, business investment, which were largely financed through credit, were particularly dynamic starting in 2004, with growth rates that in 2007 reached, respectively, 10.2% and 13.4%. Inflation was moderate, and in this generally positive context, Cyprus qualified to adopt the euro on 1 January 2008.

In this pre-crisis period, the Cypriot economy – a small, very open economy – relied in the main on two sectors: tourism and financial services.

The two key sectors of the Cypriot economy

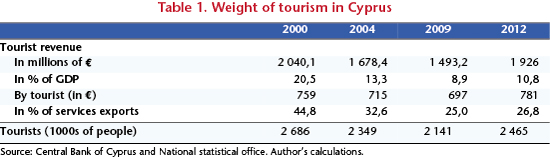

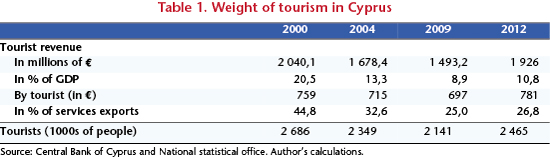

Revenue from tourism (Table 1) has provided a relatively stable financial windfall for the Cypriot economy. This (non-cyclical) flow brings in approximately 2 billion euros annually. [8] As a share of GDP, however, the weight of tourism has decreased by half since 2000, to a level of less than 11% in 2012. Likewise, the share of tourism in the export of services fell sharply during the last decade: in 2012, it accounted for 27% (against 45% in 2000). Over the last 15 years, the number of tourists has fluctuated somewhat between 2.1 million (in 2009) and 2.7 million (2000), compared with about 850,000 people who are residents of the island.

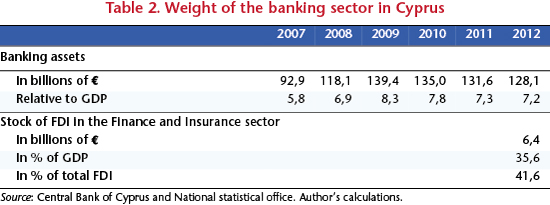

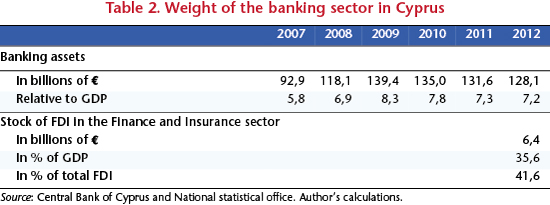

Financial services constitute the other pillar of the Cypriot economy (Table 2). Two figures give a clear idea of its significance: bank assets accounted for more than 7.2 times GDP in 2012 (with a maximum of 8.3 achieved in 2009), and the stock of FDI in the sector “Finance & Insurance” is estimated at more than 35% of GDP, i.e. more than 40% of all FDI inflows.

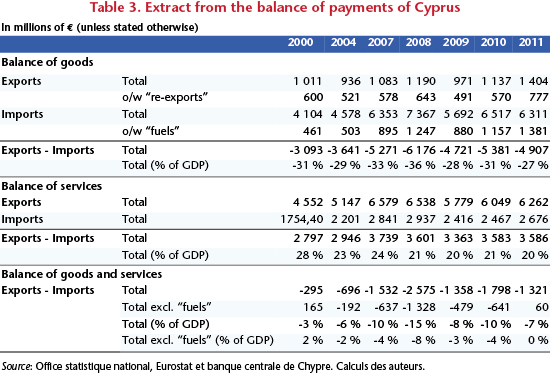

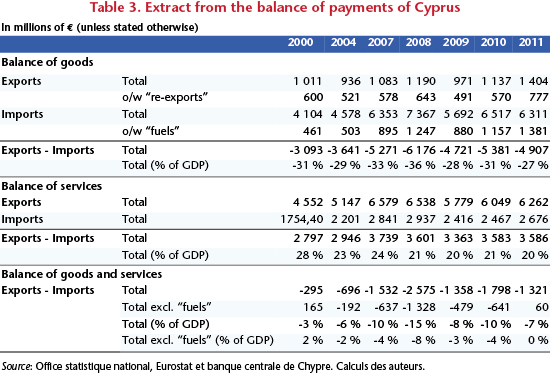

As major sources of wealth for the Cypriot economy, these two sectors have played an important role by, at least until 2007, compensating (partially) the considerable deficit in the balance of payments, which has risen continuously since the early 1990s and fluctuated at around 30% of GDP since 2000 (Table 3). The “fuel” bill has been an increasing burden on imports into Cyprus, mainly due to higher oil prices: the energy bill has tripled over the last decade, rising from 461 million euros in 2000 to 1.4 billion in 2011. As a percentage of GDP, the rise in energy costs has also been very visible, as it has shot up from 5% of GDP in 2000 to 8% in 2011.

Reducing the size of the financial sector therefore raises the question of a new growth model for the Cypriot economy, i.e. its “industrial conversion”.

The temptation to exit the euro

The plan decided by the Troika undermines the island’s growth model by penalizing the country’s hyper-financialization, and condemns it to years of recession. To avoid a long convalescence, the idea of leaving the euro zone has taken root, as it did in Greece. However, leaving the euro zone is far from a panacea. Regaining monetary sovereignty undeniably offers certain advantages, as is described by C. Antonin and C. Blot in their note, Comparative study of Ireland and Iceland: first, an internal devaluation (through lower wages) would not be as effective as an external devaluation (through exchange rates); second, fiscal consolidation is less costly when it is accompanied by a favourable exchange rate policy. Nevertheless, given the structure of the Cypriot economy, we do not think that leaving the euro is desirable.

In fact, upon leaving the euro, the Central Bank of Cyprus would issue a new currency. Assuming it remains convertible, this currency would depreciate vis-à-vis the euro. By way of comparison, between July 2007 and December 2008 the Icelandic krona lost 50% of its value vis-à-vis the euro. Such a depreciation would have two consequences:

– One, an improvement in competitiveness (the real exchange rate has appreciated by 10% since 2000), which would boost exports and help reduce the deficit in the balance of trade in goods and services (Table 1). Since the accession of Cyprus to the European Union in 2004, this balance has deteriorated as a result of several factors: first, the slowing of inflation from 2004 related to pegging the exchange rate to the euro, which encouraged the growth of real wages at a higher rate than productivity gains; and second, the boom in bank lending, with the substantial decline in risk premiums on loans as a result of accession to the EU [9]. Consumption was boosted, the competitiveness of the Cypriot economy deteriorated, and imports increased. Would exiting the euro reverse this trend? This is the argument of Paul Krugman, who supports Cyprus leaving the euro zone by evoking a tourist boom and the development of new export-oriented industries. However, according to our calculations, a 50% depreciation in the real exchange rate would result in an increase in the value of exports of 500 million euros, including 150 million from additional tourism revenue. [10] As for imports, they are weakly substitutable, as they are composed of energy and capital and consumer goods. Given the weakness of the country’s industries, Cyprus will not be able to undertake a major industrial restructuring in the short or medium term. There are therefore limits to improvements in the trade balance. Furthermore, inflation would increase, including through imported inflation, which would lead to a fall in consumer purchasing power and mitigate any competitiveness gains.

– In addition, the devaluation would substantially increase the burden of the outstanding debt, but also of private debt denominated in foreign currency. Net foreign debt in Cyprus is low, at 41% of GDP in 2012. In contrast, public debt reached 70% of GDP, or 12.8 billion euros. 99.7% of the public debt is denominated in euros or in a currency that is part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (and thus pegged to the euro), and 53% of this debt is held by non-residents. In addition, the deficit was 6.3% of GDP. If Cyprus no longer had the euro, it would without doubt default on part of its public debt, which would temporarily deprive the country of access to foreign capital, and thus require the kind of violent fiscal consolidation that Argentina went through in 2001.

The exploitation of natural gas resources

The crisis in Cyprus raises the question of the natural gas discoveries in the south of the island in the early 2000s. According to the US Geological Survey, the Levant Basin located between Cyprus and Israel could contain 3,400 billion cu.m of gas resources. By way of comparison, the entire EU has 2,400 billion cu.m (mainly in the North Sea).

Cyprus thus has a priori a major natural gas bonanza, even if all of the deposits are not located in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). At present, only one out of the twelve parcels of land belonging to the Cypriot EEZ has been subject to exploratory drilling, and in December 2011 a deposit of 224 billion cu.m of natural gas was discovered. According to the Government of Cyprus, the value of this field, called Aphrodite, is estimated at 100 billion euros[11]. The exploration of the other eleven parcels belonging to the Cypriot EEZ could prove successful (or even very successful) in terms of natural gas resources. As the licenses for the exploration of these eleven parcels are in the process of being awarded by the Cypriot authorities, the EU could have used the (sad) occasion of the rescue package to secure a portion of the aid granted to Cyprus on its gas potential. Why did the EU not seize on such an occasion?

For the EU, the discovery of the natural gas reserves is good news, in the sense that the exploitation of these deposits will help it to achieve the energy diversification that it values so highly. However, several problems have arisen, problems that darken the prospects for exploiting the gas fields in the very near future. First of all, the discovery of gas reserves in the Levant basin has revived tensions with Turkey, which occupies the northern part of the island of Cyprus and which believes it has rights to the exploitation of the fields. The growing number of Turkish military manoeuvres reflects an effort to impose its presence in the areas being surveyed and could lead to an escalation of violence in the region, especially since the Greek-Cypriot authorities (the southern part) have been working with Israel to defend the gas fields. [12] Second, even assuming that the Greek-Turkish dispute is resolved, the exploitation of the gas will require heavy investment in infrastructure, in particular the construction of an LNG tanker whose cost is estimated at 10 billion euros. Finally, there will be no immediate return on the investment, as it will take at least eight years to put in place the necessary infrastructure. In these conditions, it is understandable why the EU did not take the opportunity to secure some of the aid to Cyprus against these gas resources: exploitation is still too uncertain and, in any case, the horizon is too distant (given the immediacy required for a response to the crisis).

Furthermore, the EU would likely wind up in an awkward situation vis-à-vis several countries. If the EU supports Cyprus in the gas dispute, this comes down to supporting Israel, at the very time that the EU is holding negotiations on Turkey’s membership and is trying to build good relations in the region, including with the regimes that have emerged from the “Arab Spring”. In addition, two pipeline projects are already in competition: the South Stream project, linking Russia to Western Europe by 2015, and Nabucco, connecting Iran, via Turkey, to Western Europe by 2017. A new gas pipeline connecting the Cypriot fields to the European continent would further reduce Russia’s bargaining power, by shifting the centre of gravity of natural gas southwards. This would promote greater dispersion and intensify geopolitical divisions in Europe, between a Northern Europe (including Germany) supplied by Russia and a Southern Europe dependent on the Middle East and Turkey.

Conclusion

If in the immediacy of the crisis the EU has made the right choice (that of the “bad” and “good” bank), the question is posed in the medium / long term of a new growth model for the Cypriot economy. Given the comparative advantages of Cyprus, the exploitation of natural gas seems to offer the only serious solution for the economy’s conversion. However, for this strategy to be achievable, the EU will have to take a clear position in favour of Cyprus in the Greek-Turkish dispute.

Not only would the exploitation of the gas bring Cyprus energy self-sufficiency, it would also constitute a major source of revenue for the island. Energy costs would cease being a burden on the balance of payments (Table 1). This is especially important, because, even though tourism (another pillar of the economy) has provided a stable (non-cyclical) source of income since 2000, it is not immune to geopolitical events in the region or to new competition over tourist destinations, in particular from the “Arab Spring” countries.

Consider this simple calculation. Suppose Cyprus manages to maintain its tourism revenues at the level of 2 billion euros (an assumption that, despite the caveats outlined above, is nevertheless realistic); in the absence of industrial restructuring, if the share of the banking sector in the economy is halved (as desired by the Troika and common sense), then Cypriot GDP would return to its 2003 level, or slightly less than 12 billion euros. And GDP per capita would fall by about a third….

Industrial reconversion is thus important for the Cypriot economy, just as for other economies in crisis…. except that Cyprus has Aphrodite.

[1] See Henri Sterdyniak and Anne-Laure Delatte, ”Cyprus: a well-conceived plan, a country in ruins…”., OFCE blog, March 2013.

[2] See Céline Antonin, Would returning to the drachma be an overwhelming tragedy?, OFCE Note no. 20, 19 June 2012.

[3] For more on the dithering on the rescue plan, see Jérôme Creel, “The Cypri-hot case!”, OFCE blog, March 2013.

[4] These loans, granted via Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA), amount to 9 billion euros.

[5] Article 63 of the Treaty of the European Union prohibits restrictions on the movement of capital, but Article 64b authorizes Member states to take control measures for reasons of public order or public safety.

[6] “If the bank can’t recapitalize itself, then we’ll talk to the shareholders and the bondholders. We’ll ask them to contribute in recapitalizing the bank. And if necessary the uninsured deposit holders”, statement by Jeroen Dijsselbloem, 25 March 2013, to the Financial Times.

[7] http://www.revue-banque.fr/risques-reglementations/breve/les-creanciers-des-banques-mis-contribution

[8] The tourist revenue of Cyprus depends in the main on tourists from Britain (43% in 2011), Russia (14%), Germany and Greece (6.5 % each).

[9] On the factors worsening the current accounts, see Natixis, Retour sur la crise chypriote, novembre 2012.

[10] Estimation made using the elasticities calculated by the IMF.

[11] Not far from Aphrodite, 700 billion cu.m of deposits were discovered in the Israeli EEZ, proof that the region is rich in natural gas.

[12] The tensions between Cyprus (southern part) and Israel were resolved (peacefully) by the signing of a treaty in December 2010 defining their respective exclusive economic zones (EEZ). The two entities also plan to cooperate in the construction of common infrastructures to exploit the gas. See the analysis of Angélique Palle on the geopolitical consequences of the discovery of these natural gas resources in the Levant basin.