By Céline Antonin

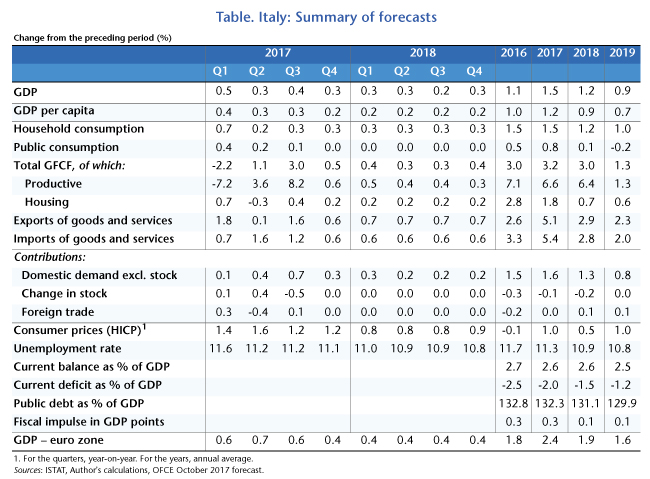

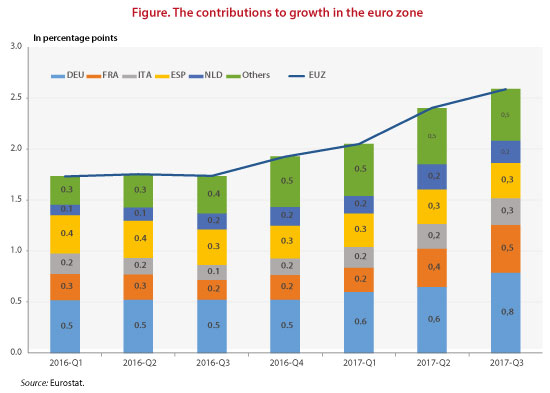

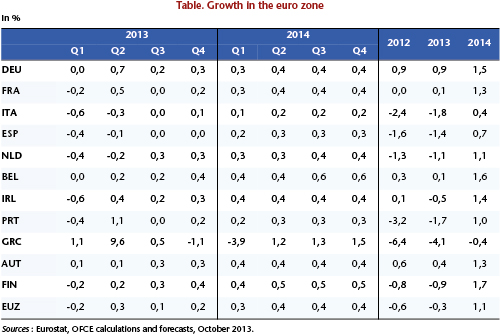

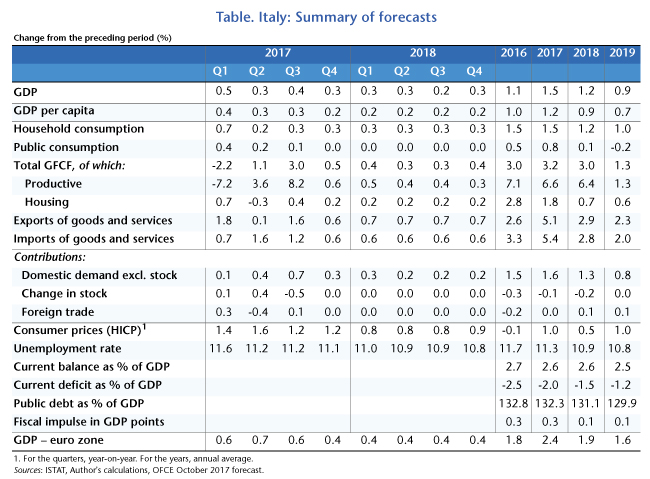

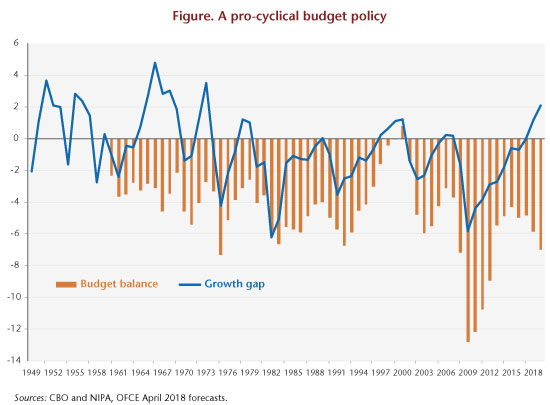

With growth in Italy of 0.4% in the third quarter of 2017 (see table below), the country’s economy seems to have recovered and is benefiting from the more general recovery in the euro zone as a whole. The improvement in growth is linked to several factors: first, the continued closing of the output gap, which had worsened sharply after a double recession (2008-2009 and 2012-2013). In addition, the expansionary fiscal policy in 2017 (+0.3 fiscal impulse), mainly targeted at businesses, and thriving consumption driven by expanding employment and rising wages explain this good performance. The increase in employment is the result of the reduction in social contributions that began in 2015 as well as the pick-up in growth in 2016 and 2017.

Despite all this, Italy remains the “sick man” of the euro zone: GDP in volume is still more than 6% below its pre-crisis level, and the recovery is less solid than for its euro zone partners. Furthermore, the public debt, now over 130%, has not yet begun to fall, potential growth remains sluggish (0.4% in 2017), and the banking sector is still fragile, as is evidenced by recent bank recapitalizations, in particular the rescue of the Monte dei Paschi di Sienna bank (see below).

In 2018-2019, Italy’s growth, while remaining above potential, should slow down. Indeed, fiscal policy will be neutral and growth will be driven mainly by domestic demand. Unemployment will fall only slowly, as the employment support measures implemented in 2017 wind down and productivity returns to its trend level [1] over the forecasting horizon (see OFCE, La nouvelle grande modération [in French], p. 71). Furthermore, the banking sector will continue its long and difficult restructuring, which will hold back the granting of bank loans.

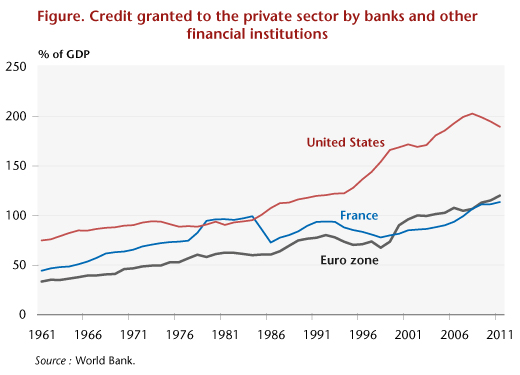

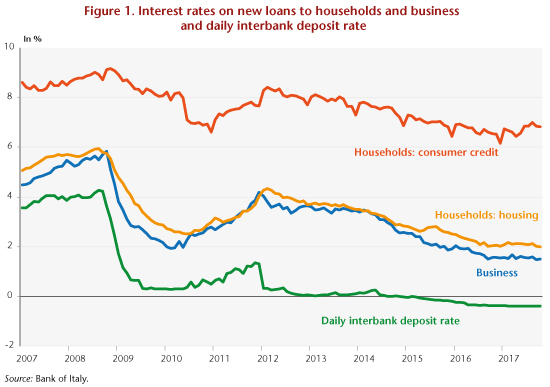

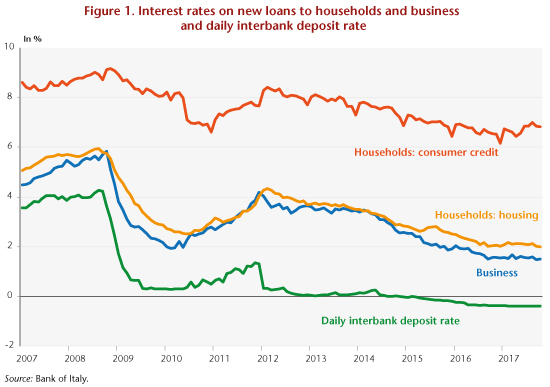

In the third quarter of 2017, the contribution of domestic demand to growth (consumption and investment) reached 0.8 point, but massive destocking attenuated the impact on growth (‑0.6 point). Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) leapt 3% in the third quarter of 2017, returning to its 2012 level, thanks to a strong increase in the productive sector (machinery, equipment and transport). Private consumption, the other pillar of domestic demand, grew on average by 0.4% per quarter between the first quarter of 2015 and the third quarter of 2017, thanks to falling unemployment and a reduction in precautionary savings. Credit conditions have improved slightly due to the quantitative easing policy pursued by the ECB, even though the channel for the transmission of monetary policy is suffering from the difficulties currently hitting the banking sector.

The number of people in employment rose to 23 million in the second quarter of 2017, back to its pre-crisis level, while the unemployment rate is declining only slowly due to the steady increase in the labour force [2]. Job creation did indeed take place between 2014 and 2017 (around 700,000 jobs created, 450,000 of them permanent), mainly due to the lowering of charges on new hires in 2015 and 2016 and the resumption of growth. Moreover, according to INPS figures, the number of new hires on permanent contracts decreased (between January-September 2016 and January-September 2017) by -3.1%, as did conversions from temporary contracts to fixed-term contracts (‑10.2%), while the numbers of new hires on temporary contracts exploded (+ 27.3%): in other words, it is mainly precarious contracts that are currently contributing to job growth. From 2018, the pace of job creation is expected to decline due to the winding down of the measures cutting employer social contributions (which represented a total of 3 billion euros) and the slowdown in economic growth. This underpins a forecast of a very slow decline in unemployment: employment is expected to rise more slowly in 2018 and 2019, but the labour force is also growing more slowly, due to a bending effect, a distortion linked to the slowdown in job creations and the retirement of the baby boom generation.

The productivity cycle in Italy is still in poor shape, despite the downward revision of the productivity trend (-1.0% for the period 2015-2019). The measures taken to cut social security contributions over the 2015-2016 period will have enriched employment growth by 27,000 jobs per quarter (extrapolating the estimates by Sestito and Viviano, Bank of Italy). Our hypothesis was for a closure of the productivity cycle over the forecast horizon, with productivity picking up pace in 2018 and 2019 [3].

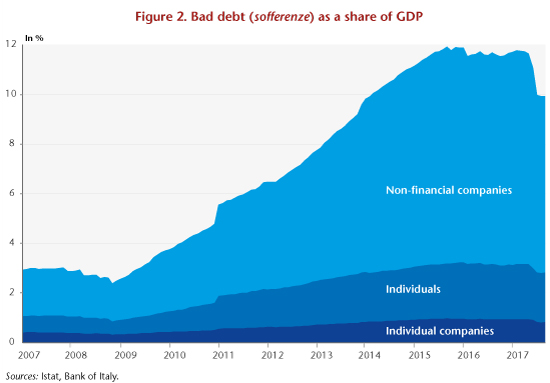

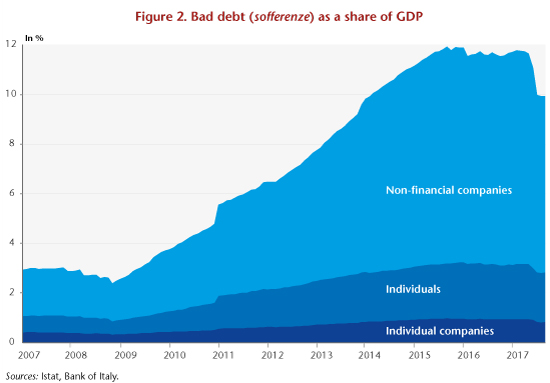

Moreover, the productive investment rate recovered strongly in the third quarter of 2017: it should continue to rise in 2018 and 2019, thanks in particular to a higher pace of extra-depreciation, to the ECB’s quantitative easing programme and to clearing up the situation of the banks, which should allow a better transmission of monetary policy (Figure 1). In addition, the amount of bad debt (sofferenze) began to fall sharply (down 30 billion euros between January and October, 2 GDP points – Figure 2). This is linked to the gradual restructuring of bank balance sheets and the economic recovery in certain sectors, particularly construction, which accounts for 43% of business bad debt.

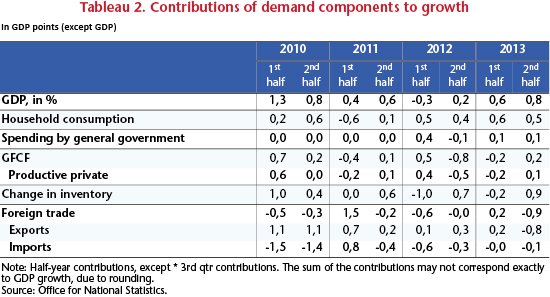

In 2017, it was domestic demand that was driving growth; the contribution of foreign trade was zero because of the dynamism of imports and the absence of any improvement in price competitiveness. We anticipate that the contribution of foreign trade will be null in 2018 and slightly positive in 2019 thanks to an improvement in competitiveness (Table).

In 2017, it was domestic demand that was driving growth; the contribution of foreign trade was zero because of the dynamism of imports and the absence of any improvement in price competitiveness. We anticipate that the contribution of foreign trade will be null in 2018 and slightly positive in 2019 thanks to an improvement in competitiveness (Table).

Fiscal policy was expansionary in 2017 (+0.3 point impulse) and supported growth. This has mainly benefited business: support for the world of agriculture, extra-depreciation, the reduction of the corporate tax rate (IRES) from 27.5% to 24% in 2017, a boost in the research tax credit, etc. 2018 should not see a noticeable increase in taxation, and spending is expected to increase slightly (0.3%). The additional public expenditure should reach 3.8 billion euros, for: youth bonuses (youth employment measures), prolongation of extra-depreciation in industry, the renewal of civil service contracts and the fight against poverty. As for public revenue, the government has ruled out a VAT hike that would have brought in 15.7 billion euros; the adjustment will therefore come from a smaller reduction in the deficit and an increase in revenue (5 billion euros forecast). To boost revenue, the government is counting on the fight against tax evasion (repatriation, recovery of VAT with electronic invoicing), and the establishment of a web tax on large companies on the Net.

A banking sector in full convalescence

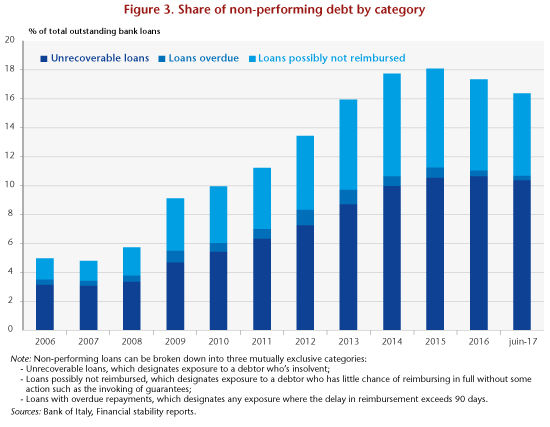

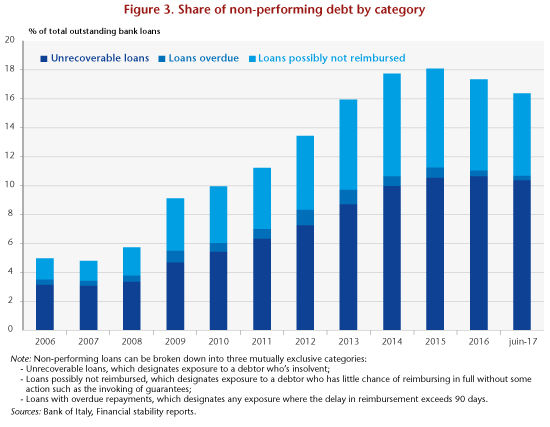

The deterioration in the situation of Italy’s businesses, in particular small and medium-sized enterprises, has led since 2009 to a sharp increase in non-performing loans. Since 2016, the situation of the Italian banking sector has improved somewhat, with a return on equity of 9.3% in June 2017 against 1.5% in September 2016. The ROE is higher than the European average (7% in June 2017) and puts the country ahead of Germany (3.0%) and France (7.2%). In addition, at the end of June 2017, the ratio of bad debt to total loans came to 16.4% (8.4% net of provisions), of which 10.4% was for unrecoverable loans (Figure 3). Banks are shedding these loans at an increasing pace with various partners (Anglo-American hedge funds, doBank, Atlante and Atlante 2 funds, etc.). Hence, between 2013 and 2016, the share of bad loans that were repaid in the year rose from 6 to 9%. Overall, the amount of bad loans was cut by 25 billion euros between 2016 and June 2017, down to 324 billion euros, of which 9 billion euros came from the liquidation of the Venetian banks (Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto banca). This improvement reflects the fact that the banks are increasingly adopting active management policies for bad debts. In addition, the 2015 Asset Seizure Reform reduced the length of property seizure proceedings.

The Italian government has implemented various reforms to cope with the difficulties facing the country’s banking sector. First, it has been working to accelerate the clearance of bad debts and to reform the law on bankruptcy. Legislative Decree 119/2016 introduced the “martial pact” (patto marciano), which makes it possible to transfer real estate used as collateral to creditors (other than the debtor’s principal residence); the real estate can then be sold by the creditor if the default lasts more than 6 months. Other rules aim at speeding up procedures: the use of digital technologies for hearings of the parties, the establishment of a digital register of ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, the reduction of opposition periods during procedures, an obligation for judges to order provisional payments for amounts not in dispute, the simplification of the transfer of ownership, etc.

The Italian government has implemented various reforms to cope with the difficulties facing the country’s banking sector. First, it has been working to accelerate the clearance of bad debts and to reform the law on bankruptcy. Legislative Decree 119/2016 introduced the “martial pact” (patto marciano), which makes it possible to transfer real estate used as collateral to creditors (other than the debtor’s principal residence); the real estate can then be sold by the creditor if the default lasts more than 6 months. Other rules aim at speeding up procedures: the use of digital technologies for hearings of the parties, the establishment of a digital register of ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, the reduction of opposition periods during procedures, an obligation for judges to order provisional payments for amounts not in dispute, the simplification of the transfer of ownership, etc.

In April 2016, the government introduced a public guarantee system (Garanzia Cartolarizzazione Sofferenze, GCS) covering bad debts, for a period of 18 months (extendable for another 18 months). To benefit from this guarantee, the bad debt must be securitized and repurchased by a securitization vehicle; the latter then issues an asset-backed security, the senior tranche of which is guaranteed by the Italian Treasury.

The Atlante investment fund was also set up in April 2016, based on public and private capital, in order to recapitalize troubled Italian banks and redeem bad debt.

There are many lessons to be drawn from the case of the Monte dei Paschi di Sienna bank (MPS, the country’s fifth-largest bank), which has been a cause of major concern. The Italian State, working in coordination with the European Commission and the ECB, had to intervene as a matter of urgency, following the failure of the private recapitalization plan at the end of 2016. A system of public financial support for banks in difficulty was introduced after a government proposal – “Salva Risparmio” [4] of 23 December 2016 – was enacted on 16 February 2017. The precautionary recapitalization of MPS was approved by the Commission on 4 July 2017 [5], in the amount of 8.1 billion euros. The Italian State increased its stake in the bank’s capital by 3.9 billion euros on the one hand, and on the other 4.5 billion euros of the bank’s subordinated bonds were converted into shares. The State is also to buy 1.5 billion euros of shares resulting from the forced conversion of bonds held by individuals (i.e. a total of 5.4 billion euros injected by the State, giving it a 70% holding in the capital of MPS). MPS will also sell 26.1 billion euros of bad debt to a special securitization vehicle, and the bank will be restructured.

Two other banks, the Venetian banks Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto banca (the 15th and 16th largest banks in the country in terms of capital), were put into liquidation on 25 June 2017, in accordance with a “national” insolvency procedure, which lies outside the framework set by the European BRRD Directive [6]. The Intesa Sanpaolo bank was selected to take over, for one symbolic euro, the assets and liabilities of the two banks, with the exception of their bad debts and their subordinated liabilities. The Italian State will invest 4.8 billion euros in the capital of Intesa Sanpaolo in order to keep its prudential ratios unchanged, and it can grant up to 12 billion euros of public guarantees.

The Italian banking sector is thus in the midst of restructuring, and the process of clearing up bad debt is underway. However, this process will take time; the ECB nevertheless seems to want to tighten the rules. In early October 2017, the ECB unveiled proposals demanding that the banks fully cover the unsecured portion of their bad debt within two years at the latest, with the secured portion of the debt to be covered within at most seven years. These proposals will apply only to new bad debt. The Italian parliament and the Italian government reacted to these announcements by warning of the risk of a credit crisis. Even though these are only proposals, for now, this indicates that it is a priority to clear Italy’s bad debt rapidly, and that the government must stay the course.

[1] Estimated according to a model using trend breaks, we estimate the productivity trend at -1.0% for the period 2015-2019, due to growth that is more job-rich.

[2] This increase in the labour force is due to a higher participation rate among older workers (aged 55-64), which is linked to the lowering of the minimum retirement age. It is also due to women’s increased participation in the labour market, as a result of the Jobs Act (extension of maternity leave, telecommuting, financial measures to reconcile work and family life, a budget of 100 million euros for the creation of childcare services, etc.).

[3] The increase in productivity per capita in market waged employment rose from -0.7 % in 2017 to 0.3 % in 2018 and 0.6 % in 2019.

[4] The Salva Risparmio Decree Law provides for the creation of a fund with 20 billion euros to support the banking sector. This allows the State to carry out precautionary recapitalizations of banks; it provides guarantees on new issues of bank debt; and it provides liquidity from the central bank under Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA). It also protects savers by providing the possibility of the State buying back subordinated bonds converted into shares prior to the public intervention.

[5] European Parliament, The precautionary precaution of Monte dei Paschi di Sienna

[6] For greater detail, see the note [in French] by Thomas Humblot, Italie : liquidation de Veneto Banca et de Banca Popolare di Vicenza, July 2017.

In 2017, it was domestic demand that was driving growth; the contribution of foreign trade was zero because of the dynamism of imports and the absence of any improvement in price competitiveness. We anticipate that the contribution of foreign trade will be null in 2018 and slightly positive in 2019 thanks to an improvement in competitiveness (Table).

In 2017, it was domestic demand that was driving growth; the contribution of foreign trade was zero because of the dynamism of imports and the absence of any improvement in price competitiveness. We anticipate that the contribution of foreign trade will be null in 2018 and slightly positive in 2019 thanks to an improvement in competitiveness (Table). The Italian government has implemented various reforms to cope with the difficulties facing the country’s banking sector. First, it has been working to accelerate the clearance of bad debts and to reform the law on bankruptcy. Legislative Decree 119/2016 introduced the “martial pact” (patto marciano), which makes it possible to transfer real estate used as collateral to creditors (other than the debtor’s principal residence); the real estate can then be sold by the creditor if the default lasts more than 6 months. Other rules aim at speeding up procedures: the use of digital technologies for hearings of the parties, the establishment of a digital register of ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, the reduction of opposition periods during procedures, an obligation for judges to order provisional payments for amounts not in dispute, the simplification of the transfer of ownership, etc.

The Italian government has implemented various reforms to cope with the difficulties facing the country’s banking sector. First, it has been working to accelerate the clearance of bad debts and to reform the law on bankruptcy. Legislative Decree 119/2016 introduced the “martial pact” (patto marciano), which makes it possible to transfer real estate used as collateral to creditors (other than the debtor’s principal residence); the real estate can then be sold by the creditor if the default lasts more than 6 months. Other rules aim at speeding up procedures: the use of digital technologies for hearings of the parties, the establishment of a digital register of ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, the reduction of opposition periods during procedures, an obligation for judges to order provisional payments for amounts not in dispute, the simplification of the transfer of ownership, etc.