By Christophe Blot, Jérôme Creel, and Xavier Timbeau

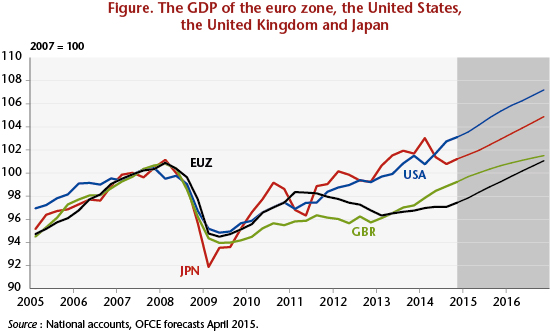

Following discussions with our colleagues from the European Commission [1], we return to the causes of the prolonged period of recession experienced by the euro zone since 2009. We continue to believe that premature fiscal austerity has been a major political error and that an alternative policy would have been possible. The economists of the European Commission for their part continue to argue that there was no alternative to the strategy they advocated. It is worth examining these conflicting opinions.

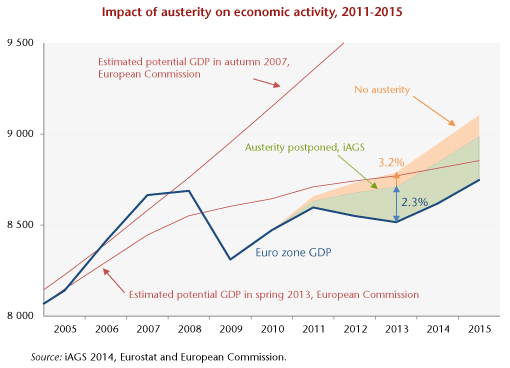

In the iAGS 2014 report (as well as in the iAGS 2013 report and in various OFCE publications), we have developed the analysis that the stiff fiscal austerity measures taken since 2010 have prolonged the recession and contributed to the rise in unemployment in the euro zone countries, and are now exposing us to the risk of deflation and increased poverty.

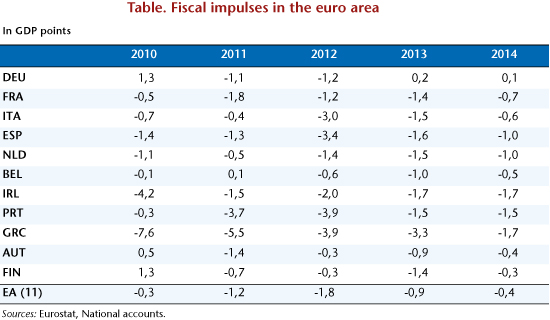

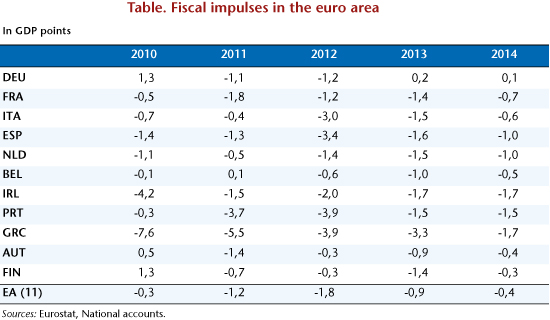

Fiscal austerity, which started in 2010 (mainly in Spain, Greece, Ireland and Portugal, with a fiscal impulse [2] for the euro zone of -0.3 GDP point that year), and then was intensified and generalized in 2011 (a fiscal stimulus of -1.2 GDP point across the euro zone, see table), and then reinforced in 2012 (‑1.8 GDP point) and continued in 2013 (-0.9 GDP point), is likely to persist in 2014 (-0.4 GDP point). At the level of the euro zone, since the start of the global financial crisis of 2008, and while taking into account the economic recovery plans of 2008 and 2009, the cumulative fiscal impulse boils down to a restrictive policy of 2.6 GDP points. Because the fiscal multipliers are high, this policy explains in (large) part the prolonged recession in the euro zone.

The fiscal multipliers summarize the impact of fiscal policy on activity [3]. They depend on the nature of fiscal policy (whether it involves tax increases or spending cuts, distinguishing between transfer, operating and investment expenditure), on the accompanying policies (mainly the ability of monetary policy to lower key rates during the austerity treatment), and on the macroeconomic and financial environment (including unemployment, the fiscal policies enacted by trading partners, changes in exchange rates and the state of the financial system). In times of crisis, the fiscal multipliers are much higher, i.e. at least 1.5 for the multiplier of transfer spending, compared with near 0 in the long-term during normal times The reason is relatively simple: in times of crisis, the paralysis of the banking sector and its inability to provide the credit economic agents need to cope with the decline in their revenues or the deterioration in their balance sheets requires the latter to respect their budget constraints, which are no longer intertemporal but instantaneous. The impossibility of generalizing negative nominal interest rates (the well-known “zero lower bound”) prevents central banks from stimulating the economy by further cuts in interest rates, which increases the multiplier effect during a period of austerity.

If the fiscal multipliers are higher in times of crisis, then a rational reduction in the public debt implies the postponement of restrictive fiscal policies. We must first get out of the situation that is causing the increase in the multiplier, and once we are back into a “normal” situation then reduce the public debt through tighter fiscal policy. This is especially important as the reduction in activity induced by tightening fiscal policy may outweigh the fiscal effort. For a multiplier higher than 2, the budget deficit and public debt, instead of falling, could continue to grow, despite austerity. The case of Greece is instructive in this respect: despite real tax hikes and real spending cuts, and despite a partial restructuring of its public debt, the Greek government is facing a public debt that is not decreasing at the pace of the budgetary efforts – far from it. The “fault” lies in the steep fall in GDP. The debate on the value of the multiplier is old but took on new life at the beginning of the crisis.[4] It received a lot of publicity at the end of 2012 and in early 2013, when the IMF (through the voice of O. Blanchard and D. Leigh) challenged the European Commission and demonstrated that these two institutions had, since 2008, systematically underestimated the impact of austerity on the euro zone countries. The European Commission recommended remedies that failed to work and then with each setback called for strengthening them. This is why the fiscal policies pursued in the euro zone reflected a considerable error of judgment and are the main cause of the prolonged recession we are experiencing. The magnitude of this error can be estimated at almost 3 percentage points of GDP for 2013 (or almost 3 points of unemployment): If austerity had been postponed until more favourable times, we would have reached the same ratio of debt-to-GDP by the deadline imposed by treaty (in 2032), but with the benefit of additional economic activity. The cost of austerity since 2011 is thus almost 500 billion euros (the total of what was lost in 2011, 2012 and 2013). The nearly 3 additional points of unemployment in the euro zone are now exposing us to the risk of deflation, which will be very difficult to avoid.

Although the European Commission follows these debates on the value of the multiplier, it (and to some extent the IMF) developed another analysis to justify its choice of economic policy in the euro zone. This analysis holds that the fiscal multipliers are negative in times of crisis for the euro zone, and for the euro zone alone. Based on this analysis, austerity should reduce unemployment. To arrive at what seems to be a paradox, we must accept a particular counterfactual (what would have happened if we had not implemented austerity policies). For example, in the case of Spain, without an immediate fiscal effort, the financial markets would have threatened to stop lending to finance the Spanish public debt. The rise in interest rates charged by the financial markets to Spain would have pushed its government into brutal fiscal restraint, the banking sector would not have survived the collapse of the value of Spain’s sovereign notes, and the increased cost of credit due to the fragmentation of the financial markets in Europe would have led to a crisis that spiralled way beyond what the country actually experienced. In this analytical model, the austerity recommended is not the result of dogmatic blindness but an acknowledgement of a lack of choice. There was no other solution, and in any case, delaying austerity was not a credible option.

Accepting the European Commission’s counterfactual amounts to accepting the idea that the fiscal multipliers are negative. It also means accepting the notion that finance dominates the economy, or at least that judgments on the sustainability of the public debt must be entrusted to the financial markets. According to this counterfactual, quick straightforward austerity would regain the confidence of the markets and would therefore avoid a deep depression. Compared to a situation of postponed austerity, the recession induced by the early straightforward budget cuts should lead to less unemployment and more activity. This counterfactual thesis was raised against us in a seminar held to discuss the iAGS 2014 report organized by the European Commission (DGECFIN) on 23 January 2014. Simulations presented on this occasion illustrated these remarks and concluded that the austerity policy pursued had been beneficial for the euro zone, thereby justifying the policy a posteriori. The efforts undertaken put an end to the sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone, a prerequisite for hoping one day to get out of the depression that began in 2008.

In the iAGS 2014 report, publically released in November 2013, we responded (in advance) to this objection based on a very different analysis: massive austerity did not lead to an end to the recession, contrary to what had been anticipated by the European Commission following its various forecasting exercises. The announcement of austerity measures in 2009, their implementation in 2010 and their reinforcement in 2011 never convinced the financial markets and failed to prevent Spain and Italy from having to face higher and higher sovereign rates. Greece, which went through an unprecedented fiscal tightening, plunged its economy into a deeper depression than the Great Depression, without reassuring anyone. Like the rest of the informed observers, the financial market understood clearly that this drastic remedy would wind up killing the patient before any cure. The continuation of high government deficits is due largely to a collapse in activity. Faced with debt that was out of control, the financial markets panicked and raised interest charges, further contributing to the collapse.

The solution is not to advocate more austerity, but to break the link between the deterioration in the fiscal situation and the rise in sovereign interest rates. Savers need to be reassured that there will be no default and that the state is credible for the repayment of its debt. If that means deferring repayment of the debt until later, and if it is credible for the State to postpone, then postponement is the best option.

Crucial to ensuring this credibility were the intervention of the European Central Bank during the summer of 2012, the initiation of the project for a banking union, and the announcement of unlimited intervention by the ECB through Outright Monetary Transactions (Creel and Timbeau (2012), which are conditional upon a programme of fiscal stabilization. These elements convinced the markets almost immediately, despite some institutional uncertainty (particularly concerning the banking union and the state of Spain’s banks, and the judgment of Germany’s Constitutional Court on the European arrangements), and even though OMT is an option that has never been implemented (in particular, what is meant by a programme to stabilize the public finances conditioning ECB intervention). Furthermore, in 2013 the European Commission negotiated a postponement of fiscal adjustment with certain Member States (Cochard and Schweisguth (2013). This first tentative step towards the solutions proposed in the two IAGS reports gained the approval of the financial markets in the form of a relaxation of sovereign spreads in the euro zone.

Contrary to our analysis, the counterfactual envisaged by the European Commission, which denies the possibility of an alternative, assumes an unchanged institutional framework [5]. Why pretend that the macroeconomic strategy should be strictly conditioned on institutional constraints? If institutional compromises are needed in order to improve the orientation of economic policies and ultimately to achieve a better result in terms of employment and growth, then this strategy must be followed. Since the Commission does not question the rules of the game in political terms, it can only submit to the imperatives of austerity. This form of apolitical stubbornness was an error, and in the absence of the ECB’s “political” step, the Commission was leading us into an impasse. The implicit pooling of the public debt embodied in the ECB’s commitment to take all the measures necessary to support the euro (the “Draghi put”) changed the relationship between the public debt and sovereign interest rates for every country in the euro zone. It is always possible to say that the ECB would never have made this commitment if the countries had not undertaken their forced march towards consolidation. But such an argument does not preclude discussing the price to be paid in order to achieve the institutional compromise. The fiscal multipliers are clearly (and strongly) positive, and it would have been good policy to defer austerity. There was an alternative, and the policy pursued was a mistake. It is perhaps the magnitude of this error that makes it difficult to recognize.

[1] We would like to thank Marco Buti for his invitation to present the iAGS 2014 report and for his suggestions, and also Emmanuelle Maincent, Alessandro Turrini and Jan in’t Veld for their comments.

[2] The fiscal impulse measures the restrictive or expansionary orientation of fiscal policy. It is calculated as the change in the primary structural balance.

[3] For example, for a multiplier of 1.5, tightening the budget by 1 billion euros would reduce activity by 1.5 billion euros.

[4] See Heyer (2012) for a recent review of the literature.

[5] The institutional framework is here understood broadly. It refers not only to the institutions in charge of economic policy decisions but also to the rules adopted by these institutions. The OMT is an example of a rule change adopted by an institution. Strengthening the fiscal rules is another element of a changing institutional framework.