By Catherine Mathieu and Henri Sterdyniak

The result of the referendum of 23 June 2016 in favour of leaving the European Union has led to a period of great economic and political uncertainty in the United Kingdom. It is also raising sensitive issues for the EU: for the first time, a country has chosen to leave the Union. At a time when populist parties are gaining momentum in several European countries, Euroscepticism is rising in others (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia), and the migrant crisis is dividing the Member States, the EU-27 must negotiate Britain’s departure with the aim of not offering an attractive alternative to opponents of European integration. There can be no satisfactory end to the UK-EU negotiations, since the EU’s goal cannot be an agreement that is favourable to the UK, but, on the contrary, to make an example, to show that leaving the EU has a substantial economic cost but no significant financial gain, that it does not give room for developing an alternative economic strategy.

According to the current timetable, the UK will exit the EU on 29 March 2019, two years after the official UK government announcement on 29 March 2017 of its departure from the EU. Negotiations with the EU officially started in April 2017.

So far, under the auspices of the European Commission and its chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, the EU-27 has maintained a firm and united position. This position has hardly given rise to democratic debates, either at the national level or European level. The partisans of more conciliatory approaches have not expressed themselves in the European Council or in Parliament for fear of being accused of breaking European unity.

The EU-27 are refusing to question, in any respect, the way that the EU is functioning to reach an agreement with the UK; they consider that the four freedoms of movement (goods, services, capital and persons) are inseparable; they are refusing to call into question the role of the European Court of Justice as the supreme tribunal; they are rejecting any effort by the UK to “cherry pick”, to choose the European programmes in which it will participate. At the same time, the EU-27 countries are seizing the opportunity to question the status of the City, Northern Ireland (for the Republic of Ireland) and Gibraltar (for Spain).

Difficult negotiations

On 29 April 2017, the European Council adopted its negotiating positions and appointed Michel Barnier as chief negotiator. The British wanted to negotiate as a matter of priority the future partnership between the EU and the UK, but the EU-27 insisted that negotiations should focus first and foremost on three points: the rights of citizens, the financial settlement for the separation, and the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. The EU-27 has taken a hard line on each of these three points, and has refused to discuss the future partnership before these are settled, banning any bilateral discussions (between the UK and a member country) and any pre-negotiation between the UK and a third country on their future trade relations.

On 8 December 2017, an agreement was finally reached between the United Kingdom and the European Commission on the three initial points[1]; this agreement was ratified at the European Council meeting of 14-15 December[2]. However, strong ambiguities persist, especially on the question of Ireland.

The European Council accepted the British request for a transitional period, with this to end on 31 December 2020 (so as to coincide with the end of the current EU budgeting). Thus, from March 2019 to the end of 2020, the UK will have to respect all the obligations of the single market (including the four freedoms and the competence of the CJEU), even though it no longer has a voice in Brussels.

The EU-27 agreed to open negotiations on the transition period and the future partnership. These negotiations were to culminate at the European summit in October 2018 in an agreement setting out the conditions for withdrawal and the rules for the transition period while outlining in a political statement the future treaty determining the relations between the United Kingdom and the EU-27, so that the European and British authorities have time to examine and approve them before 30 March 2019.

However, both the EU-27 and the UK have proclaimed that “there is no agreement on anything until there is an agreement on everything”, meaning that the agreements on the three points as well as on the transition period are subject to agreement on the future partnership.

Negotiations for the British side

The members of the government formed by Theresa May in July 2016 were divided on the terms for Brexit from the outset: on one side were supporters of a hard Brexit, including Boris Johnson, who was then in charge of foreign affairs, and David Davis, then tasked to negotiate the UK’s departure from the EU; on the other side were members who favoured a compromise to limit Brexit’s impact on the British economy, including Philip Hammond, Chancellor of the Exchequer. The proponents of a hard Brexit had argued during the campaign that leaving the EU would mean no more financial contributions to the EU, so the savings could be put to “better use” financing the UK health system; that the United Kingdom could turn to the outside world and freely sign trade agreements with non-EU countries, which would be beneficial for the UK economy; and that getting out of the shackles of European regulations would boost the economy. The hard Brexiteers argue against giving in to the EU-27’s demands, even at the risk of leaving without an agreement. The goal is to get free of Europe’s constraints and “regain control”. For those in favour of a compromise with the EU, it is essential to avoid a no-deal Brexit – “going over the cliff” would be detrimental to British business and jobs. In recent months, it has been this camp that has gradually strengthened its positions within the government, leading Theresa May to ask the EU-27 for a transitional period during her Florence speech of September 2017, which also responded to the demands of British business representatives (including the Confederation of British Industrialists, the CBI). On 6 July 2018, Theresa May held a government meeting in the Prime Minister’s Chequers residence to agree on British proposals on the future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union. The concessions made in recent months by the British government together with the Chequers proposals led David Davis and Boris Johnson to resign from the Cabinet on 8 July 2018.

On 12 July 2018, the British government published a White Paper on the future partnership[3]. It proposes a “principled and practical Brexit”[4]. This must “respect the result of the 2016 referendum and the decision of the UK public to take back control of the UK’s laws, borders and money”. It is about building a new relationship between the UK and the EU, “broader in scope” than the current relationship between the EU and any third country, taking into account the “deep history and close ties”.

The White Paper has four chapters: economic partnership, security partnership, cross-cutting and other cooperation, and institutional arrangements. As far as the economic partnership is concerned, the agreement must allow for a “broad and deep economic relationship with the rest of the EU”. The United Kingdom proposes the establishment of a free trade area for goods. This would allow British and European companies to maintain production chains and avoid border and customs controls. This free trade area would “meet the commitment” of maintaining the absence of a border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The UK would align with the relevant EU rules to allow friction-free trade at the border; it would participate in the European agencies for chemicals, aviation safety and medicines. The White Paper proposes applying EU customs rules to the imports of goods arriving in the UK on behalf of the EU and collecting VAT on these goods also on its behalf.

For services, the UK would regain its regulatory freedom, agreeing to forego the European passport for financial services, while referring to provisions for the mutual recognition of regulations, which would preserve the benefits of integrated markets. It wishes to maintain cooperation in the fields of energy and transport. In return, the UK is committed to maintaining cooperative provisions on competition regulation, labour law and the environment. Freedom of movement would be maintained for citizens of the EU and the UK.

The security partnership would include the maintenance of cooperation on police and legal matters, the UK’s participation in Europol and Eurojust, and coordination on foreign policy, defence, and the fight against terrorism.

The White Paper proposes close cooperation on the circulation and protection of personal data as well as agreements for scientific cooperation in the fields of innovation, culture, education, development, international action, and R&D in the defence and aerospace sector. The UK wishes to continue to participate in European programmes on scientific cooperation, with a corresponding financial contribution. Finally, the United Kingdom would no longer participate in the common fisheries policy, but proposes negotiations on the subject.

In institutional matters, the UK proposes an Association Agreement, with regular dialogue between EU and UK Ministers, in a Joint Committee. The UK would recognize the exclusive jurisdiction of the CJEU to interpret EU rules, but disputes between the UK and the EU would be settled by the Joint Committee or by independent arbitration.

Up to now Theresa May has tried to assuage both the hard Brexiteers – the UK will indeed leave the EU – and supporters of a flexible Brexit – the UK wants a deep and special partnership with the EU. Theresa May regularly repeats that the UK is leaving the EU but not Europe, but her compromise position is not satisfying supporters of a net Brexit. In September 2018, Boris Johnson has been accusing Theresa May of capitulating to the EU: “At every stage in the talks so far, Brussels gets what Brussels wants…. We have wrapped a suicide vest around the British Constitution – and handed the detonator to Michel Barnier. We have given him a jemmy with which Brussels can choose – at any time – to crack apart the union between Great Britain and Northern Ireland”[5]. According to Johnson, the Chequers plan loses all the benefits of Brexit. The Remainers, those in favour of staying in the EU, are campaigning for a new referendum. This is nevertheless unlikely. Theresa May rejects it out of hand as a “betrayal of democracy”.

The Conservative Party’s annual convention, to be held from September 30 to October 3, could see Boris Johnson or Jacob Rees-Mogg[6] run for head of the Party. They do not have majority support, however, and the polls show Theresa May with greater popularity than her challengers. Barring a dramatic twist, Theresa May will continue to lead the Brexit negotiations in the coming months.

The British Parliament decided last December 13 that it will have a vote on any agreement with the European Union. So Theresa May must also find a parliamentary majority concerning the UK’s orderly withdrawal, in the face of opposition from both Remainers and hard Brexiteers, which will require the support of some Labour MPs and will therefore be difficult.

The proposals of the July White Paper were not deemed acceptable by Michel Barnier. In August, Jeremy Hunt, the UK’s new Foreign Minister, estimated the risks of a lack of agreement at 60%. On 23 August 2018, the government published 25 technical notes (out of 80 planned) that spell out the government’s measures to be taken in case of a no-deal exit in March 2019. Their objective is to reassure businesses and households about the risks of shortages of imported products, including certain food products and medicines. At the time these notes were published, Dominic Raab, the new Minister in charge of the Brexit negotiations, took care to recall that the government does want an agreement be signed and that the negotiators agree on 80% of the provisions of the withdrawal agreement.

If the EU-27 remains inflexible, the British government will face a choice between leaving without an agreement, which the “hard” Brexiteers are ready to do, and making further concessions. Philip Hammond recalled the risks of failing to reach an agreement. But Theresa May is sticking to her line that the lack of an agreement would be preferable to a bad deal. On 28 August, she echoed the words of WTO Director-General Roberto Azevedo, that leaving without an agreement would not be “the end of the world”, but nor would it be “a walk in the park”. In an opinion column in the Sunday Telegraph of 1 September 2018, she reaffirmed her desire to build a United Kingdom that is stronger, more daring, based on meritocracy, and adapted to the future, outside the EU.

The negotiations from the EU viewpoint

The EU-27 is refusing that the UK could stay in the single market and the customs union while choosing which rules it wants to apply. It does not want the UK to benefit from more favourable rules than other third countries, in particular the current members of the European Economic Area (the EEA: Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein) or Switzerland. EEA members currently have to integrate all the single market legislation (in particular the free movement of persons) and contribute to the European budget. They benefit from the European passport for financial institutions, while Switzerland does not.

In December 2017, Michel Barnier made it clear that lessons had to be drawn from the United Kingdom’s refusal to respect the four freedoms, its regaining of its commercial sovereignty, and its termination of its recognition of the authority of the European Court of Justice. This rules out any possibility of its participation in the single market and the customs union. The agreement with the UK will be a free trade agreement, along the lines of the agreements signed with Canada (the CETA), South Korea and more recently Japan. It will not concern financial services.

During the 2018 negotiations, the EU-27 was not particularly conciliatory about a series of issues: the UK’s obligation to apply all EU rules and the guarantee of the freedom of establishment of people until the end of the transitional period; the Irish border (arguing that the absence of physical borders was not compatible with the UK’s withdrawal from the customs union, demanding that Northern Ireland remain in the single market as long as the UK does not come up with a solution guaranteeing the integrity of the internal market without a physical border with Ireland); the role of the CJEU (which must have jurisdiction to interpret the withdrawal agreement); the EU’s decision-making autonomy (refusing the establishment of permanent joint decision-making bodies with the UK); and even Gibraltar and the British military bases in Cyprus.

Thus, on 2 July 2018, Michel Barnier[7] accepted the principle of an ambitious partnership, but refused any land border between the two parts of Ireland, while indicating that a land border is necessary to protect the EU (this would mean that the only acceptable deal would involve a border crossing between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, which is unacceptable to the UK). He refused that the EU “loses control of its borders and its laws”. Barnier therefore rejected the idea that the UK would be responsible for enforcing European customs rules and collecting VAT for the EU. He insisted that future cooperation with the UK could not rely on the same degree of trust as between EU member countries. He called for precise and controllable commitments from the United Kingdom, particularly with respect to health standards and the protection of Geographical indications. He wanted the agreement to be limited to a free trade agreement, with UK guarantees on regulations and state subsidies, and with cooperation on customs and regulations.

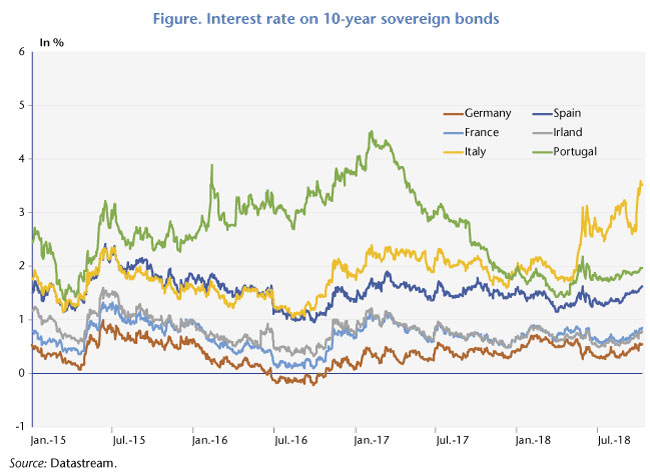

The UK would have to renegotiate all trade agreements, both with the EU and with third countries. These agreements will probably take a long time to set up, and in any case more than two years. The lack of preparation and the disorganization with which the UK has tackled the Brexit negotiations augurs poorly for its ability to negotiate such agreements quickly. The matter of re-establishing customs controls is crucial and delicate, whether in Ireland, Gibraltar or Calais. Many multinational corporations will relocate their factories and headquarters to continental Europe. The loss of the financial passport is a given. It is on this point that the British could see further losses, given the weight of the City’s business (7.5% of British GDP). The United Kingdom will have to choose between abiding by European rules to maintain some access to European markets and entering into confrontation by a policy of liberalization. The EU-27 could seize the opportunity of the UK’s departure to return to a Rhine-based financial model, centred on banks and credit rather than on markets or, on the contrary, it could try to supplant the City’s market activities through liberalization measures. It is the second branch of these alternative that will prevail.

Choosing between three strategies

So far, the EU-27 countries have taken a position that is tough but easy to hold: since it is the UK that has chosen to leave the Union, it is up to it to make acceptable proposals for the EU-27, with regard both to its withdrawal and to subsequent relations. This is the approach that led to the current stagnant situation. The EU-27 now has to choose between three strategies:

– Not to make proposals acceptable to the British and resign themselves to a no-deal Brexit: relations between the UK and the EU-27 would be managed according to WTO principles; and the financial terms of the divorce would be decided legally. The United Kingdom would regain full sovereignty. There are two reasons to fear this scenario: trade would be disrupted by the re-erection of customs barriers in ports and in Ireland; and this “hard Brexit” would encourage the UK to become a tax and regulatory haven, meaning that the EU would be faced with the alternative either of following along or retaliating, both of which would be destructive;

– Face the issue head on and establish a third circle for countries that want to participate in a customs union with the EU countries in the short term, i.e. the United Kingdom and the EEA countries. It is within this framework that agreements on technical regulations and standards for goods and services would be negotiated. Thus, “freedom of trade” issue would be dissociated from issues of political sovereignty. However, this poses two problems: these agreements would need to be negotiated in technical committees where public opinion and national parliaments such as the European Parliament would have little voice. The fields of the customs union are problematic, in particular for fiscal matters, financial regulations, and the freedom of movement of persons and services;

– Choose the “special and deep partnership” solution, which would entail reciprocal concessions. This would necessarily be able to serve as a model for relations between the EU and other countries. It would include a customs union limited to goods, committees for harmonizing standards, piecemeal agreements for services, the right of the UK to limit the movement of persons, undoubtedly a court of arbitration (which would limit the powers of the CJEU), and a commitment to avoid fiscal and regulatory competition. As is clear, this would satisfy neither supporters of a hard Brexit nor supporters of an autonomous and integrated European Union.

[1] See: Joint report from the negotiators of the EU and the UK government on progress during phase 1 of negotiations under Article 50 on the UK’s orderly withdrawal from the EU, 8 December 2017.

[2] See Catherine Mathieu and Henri Sterdyniak: Brexit, réussir sa sortie, Blog de l’OFCE, 6 December 2017.

[3] HM Government: “The future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union”, July 2018.

[4] The expression is in the original text: “A principled and practical Brexit”. Translations of the summary note in the 25 languages of the EU are available on the web site of the Department for Exiting the European Union. The French version uses the term: “Brexit vertueux et pratique”.

[5] Opinion column by Boris Johnson, Mail on Sunday, 9 September 2018.

[6] Favourable to a hard Brexit – from Eton-Oxford, a traditionalist Catholic who is opposed to abortion, public spending and the fight against climate change.

[7] See Un partenariat ambitieux avec le Royaume-Uni après le Brexit , 2 July 2018.

A very strong fiscal stimulus in 2019

A very strong fiscal stimulus in 2019