by Xavier Ragot, with contributions from Céline Antonin, Elliot Aurissergues, Christophe Blot, Eric Heyer, Paul Malliet, Mathieu Plane, Raoul Sampognaro, Xavier Timbeau, Grégory Verdugo.

The purpose of this analysis is to open up discussion about how the war in Ukraine will affect the French economy. Such an assessment is of course uncertain, as it requires a forecast of diplomatic and military developments and in particular involves critical assumptions about sanctions and economic policy responses.

If consequences that are deemed negative are identified, this should not be read as a criticism of these policy choices, but rather as a contribution to how best to limit their negative impacts.

This document is intended as a summary and refers to relevant work for further consideration. Ongoing study will clarify the analyses and the relevant calculations.

The war in Ukraine will affect the French economy through eleven different channels.

I – The economic shock: Short-term effects

1) The first effect is of course on France’s energy bill

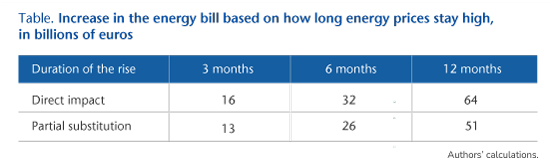

Increases in the price of gas and oil will reduce the purchasing power of French households and raise production costs for business. The gas price is the first unknown. The average daily price in 2019 was €14.6/MWh, before falling to €9.6/MWh in 2020 due to the pandemic. The price per MWh reached €210 on 10 March 2022! This high level will not last. A level of €100/MWh is a realistic assumption, which would constitute a six-fold increase in price from 2019. Second, the higher gas prices will not be passed on to households immediately, because many contracts have expired (Antonin, 2022) and the government will wind up bearing part of the energy bill through the regulation of gas prices. However, the price increase on imports will be paid by domestic agents.

France imported 632 TWh of gas in 2019 and 533 TWh in 2020, as the pandemic slowed activity. But what counts most are net imports, which are lower. The cost of net gas imports in 2019 was €8.6 billion. Imports in 2022 will be affected by a possible economic slowdown but also by gas storehouses. For 2022, a working hypothesis could start from the level of net imports in 2019. Applying an increase of €85/MWh, this results in an additional cost of around €40 billion if the increase were to last one year. If the higher price were to last longer, then it would generate substitution effects in the medium term, as discussed below.

The price of oil is equally difficult to predict, as it depends on the behaviour of strategic players, such as OPEC. The price of a barrel of Brent crude fluctuated between USD 60 and USD 70 in 2019. It rose to USD 133 on 8 March, before falling back to USD 114 after OPEC announced a boost in production. The price of oil will, much like gas, depend on the sanctions on Russia; Russian crude represented around 10% of France’s purchases in 2020 and in 2019 constituted about 4.8% of the world’s known reserves. We could assume an average price of 110 dollars (or 100 euros, which is consistent with the EIA analysis). In 2019, France’s crude oil bill was €21.8 billion, to which must be added €13.3 billion of refined products. Assuming unchanged demand and using these same amounts, we end up with a total oil bill of 58.5 billion euros, i.e. an extra cost of 24 billion euros. The euro/dollar exchange rate could also fluctuate during the crisis, with a probable depreciation of the euro that is difficult to estimate at present. As a result, a constant exchange rate of 1.1 will be kept.

This increase will necessarily generate moves towards import substitution and reduction. These effects have been studied for the German economy (with references to the measures) by Bachman et al. (2022), who focus only on substitution effects. Using the literature (Ladandeira et al., 2017), they assume an elasticity of -0.2. In the case of a reduction in the quantity of gas and oil, how much residual capacity do firms have to produce? The answer to this question depends on assumptions about the extent energy can be substituted by other factors. Depending on these assumptions, all of which are realistic, the estimate for Germany ranges from 0.7 GDP points to 2.5 GDP points, or even more due to supply effects alone.

For France, a concrete example of substitution would be a reduction in heating: a 1° reduction in heating leads to a 7% reduction in gas consumption, i.e. a reduction of gas consumption by 4.2 billion m3, whereas 14.7 billion m3 of Russian gas is consumed.

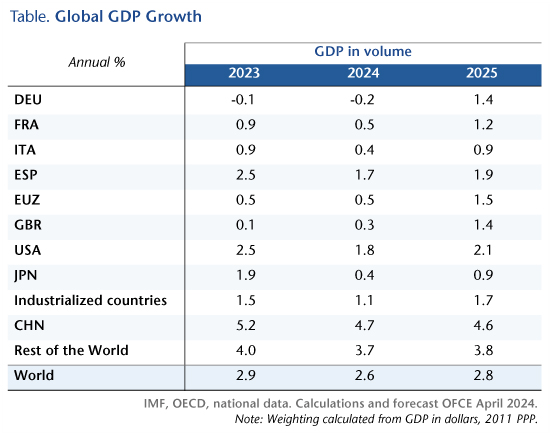

The following table summarises estimates of how much price increases will raise costs, using various assumptions.

The table shows the uncertainty of the estimate depending on the duration of the price rise and the assumption of partial short-term substitution. The figure of 64 billion euros is close to three GDP points, which would be a significant shock to the French economy. A duration of six months with substitution behaviour would lead to a shock of one GDP point. Here we see the critical importance of political uncertainty.

2) Macroeconomic effect of rising energy costs

The primary effects of higher energy prices would be a reduction in household purchasing power, an increase in business production costs and higher costs to the state due to regulating prices. The impact on growth would proceed through complex mechanisms. As mentioned above, it occurs through substitution effects but also through the diffusion of energy prices to production prices and wages.

The OFCE has estimated the macroeconomic impact of a rise in energy prices in three different ways. First, by using two macroeconomic models, the emod.fr model, also used in forecasting, and the Threeme model, which breaks down energy consumption by sector (Antonin, Ducoudré, Péleraux, Rifflart, Saussay, 2015). Another strategy has been to use possibly non-linear econometrics (Heyer and Hubert, 2016 and Heyer and Hubert, 2020). Note that the latter work includes substitution possibilities measured by the elasticities mentioned above.

The results are as follows. In the model-based approach, a long-term oil price increase of 10 dollars leads to 0.1% to 0.15% less GDP growth and 0.6% inflation in the first year. With the econometric approach, a 10 dollar oil price increase reduces growth by 0.2% and leads to a 0.4% increase in inflation, with a relatively linear effect and a maximum impact after four quarters.

Because of the size of the shock, it is difficult to know whether to consider the high ranges because of the non-linearities or the low ranges because of a greater substitution effort and a fall in the savings rate. Furthermore, the estimate is made for oil and not for gas. For this reason, we will consider average effects, without seeking to maximise the fall in GDP. Thus, an increase of 40 dollars (compared to the situation in 2019), which is increased proportionally to take account of increases in the price of gas as well, leads to a fall in GDP of about 2.5 GDP points in the upper range and an increase in inflation of 3% to 4%. This amount corresponds to a multiplier for the negative shock on energy expenditure of -1. With unchanged business behaviour and unchanged public policy, this fall in GDP translates into a drop of the same order in market employment, so about 600,000 jobs (change compared with a non-war environment). In the low range (short duration and substitution), we obtain a fall in GDP five times smaller at 0.5 GDP points.

At this stage, this estimate does not take into account the effect of the conflict on other commodities, cereals or precious metals, which are of secondary importance compared to energy prices and are discussed by COFACE.

3) Uncertainty channel

Modelling the effect of the war in Ukraine depends heavily on the reaction of households and businesses to the uncertainty generated by the war. In an environment like this, the savings rate is expected to rise in the medium term (after purchases of basic necessities), which would aggravate the depth of a recession. However, after the Covid-19 crisis, households in France have an excess of savings of 12% of annual income (166 billion euros, OFCE Policy Brief no. 95), which they could dip into to pay the additional energy bill without changing their consumption habits. This attitude depends crucially on the perceived duration of the shock. A shock that is expected to last very long may lead to an additional increase in savings.

Companies’ wait-and-see attitude (before knowing which way markets are going) is leading to a downturn in investment. For business, the period of high uncertainty during the pandemic was marked by a good level of investment, partly due to public support (OFCE Policy Brief no. 95).

The third effect of the uncertainty channel is an increase in precautionary savings and a search for secure savings. As a result, savings are more likely to be directed towards safe assets, including public debt, and the real interest rate on France’s public debt may fall. After the outbreak of the conflict, rates did indeed fall in Germany (0.20 points), the United States (0.15), France (0.20), Italy (0.35) and Spain (0.2). In the longer term, how rates change will depend on how the policy of the European Central Bank (ECB) is perceived, which is discussed below. The search for safe assets will also cause the stock markets to fall and lead to negative effects on financial wealth, which won’t modify consumption in France much.

4) Redistributive effects

Higher energy prices will affect households differently and will disproportionately hit the poorest households with the lowest savings rates (Malliet, 2020).

There is considerable heterogeneity in the structure of spending on energy products. According to data from the 2017 Budget des familles survey conducted by INSEE, 10% of the consumption expenditure of the households in the poorest decile goes on electricity, gas and other fuel for the home and on fuel for transport. At the other end of the scale of living standards, households in the richest decile spend less than 7% on these items. On the other hand, Malliet (2020) shows that there is still considerable heterogeneity in the structure of consumption of these products even within a given decile. There is a significant proportion of the population that is highly exposed to certain energy prices, which requires that targeted measures be adopted that take into account this extraordinary exposure to certain goods for which – unless the household makes a major investment – there are few readily available substitutes.

The anti-redistributive aspect of a rise in energy prices therefore leads to a marked drop in the consumption of households with the lowest savings rate. This effect, in addition to the uncertainty channel, leads to a drop in aggregate demand and activity. Compensation for the loss of purchasing power induced by the rise in the price of oil and gas of 30% thus comes to 20 billion euros in the high range.

5) Destabilising financial effects

In addition to the average effect on interest rates, the sanctions that entail the exclusion of certain Russian banks from the Swift system is leading the banks to default on payments. Freezing the Russian central bank’s assets will generate difficulties that will probably lead to an explicit default on Russia’s public debt (a first since 1998) if the conflict continues for a few more weeks. According to the rating agencies, the risk of a sovereign default is imminent. A decree already allows for the repayment of the public debt to certain countries in roubles. The risk of a default on Russia’s debt is approaching one (measured by the CDS), and evaluations of the impact of sanctions on Russia’s debt point to a fall in GDP of between 7.5% and 10% in 2022 (Coface). The risk on Turkish and South African debt is also mounting.

The exposure of French and European banks and investment funds to Russian risk (public and private) is difficult to estimate because of possible contagion effects. The amount of external public debt is, however, low, estimated at USD 60 billion. The ECB can be trusted to intervene in the event of heightened financial instability, but the risk of a tightening of credit is likely.

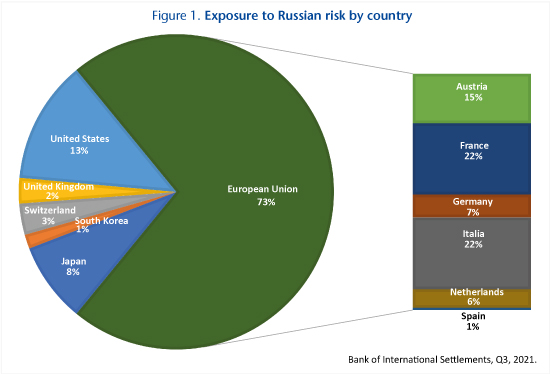

The following graph shows the exposure to Russian risk by country, measured by residents’ consolidated position in Russian assets (Bank for International Settlements data).

We see that France’s exposure is high, at 22%, as is Italy’s. However, this exposure doesn’t include the possible contagion effects of financial crises.

II – Fiscal policy response

How the economy fares after such a shock will depend on the fiscal and monetary response.

6) Reception of refugees

First of all, while the primary purpose of taking in refugees obviously is not economic, this will generate expenditures that will probably be financed by debt and so will have an effect on activity. The experience of the last refugee crisis in 2016 leads to a first estimate. As Jean Pisani-Ferry notes, according to UNHCR analyses, Germany’s intake of 750,000 refugees in 2016 called for a budgetary effort of 9 billion euros, i.e. about 10 billion euros per million refugees. For an estimated 4 million refugees (given that currently the number is about 2.5 million), this leads to a temporary cost of 40 billion for Europe, which, on the scale of Europe, is not all that much but which for the countries hosting the most refugees, such as Poland, is huge.

The central question, however, is how to organise support for these millions of refugees. Gregory Verdugo has discussed the challenges for the European asylum system from 2019 and the integration of refugees. Note that the long-term impact of migration is positive, even if today’s refugees are mainly women and children. Of course these economic considerations are not central to how to support the refugees.

7) Support for the most vulnerable households

As noted, the rise in energy and food prices is strongly anti-redistributive and disproportionately affects the poorest households. For this reason, to offset the rise in inflation at the end of 2021, the French state has introduced an inflation allowance and exceptional support in the form of a €100 energy voucher, for a total estimated cost of €4.4 billion (€3.8 billion and €0.6 billion). The government has announced that it will spend €24 billion, or about 1 GDP point, to offset the rise in energy prices. This is the order of magnitude of the increase in the oil bill, without taking into account the increase in the price of gas. The OFCE Policy Brief on purchasing power, published on 17 March, deals with these issues.

This price increase will make the country poorer (negative supply shock) due to domestic dependence on energy imports. Responding to the shock with a wage increase is not a good solution, as it leads to higher prices and induced inflation, as companies in turn would face higher production costs. Support for vulnerable households should therefore be fiscal and not wage-based. The low interest rates on France’s public debt opens up some fiscal space that should be used temporarily.

8) Energy investment

Reducing dependence on Russian oil and gas (which will be compulsory if there is an embargo) will lead to additional investments. The recent IAE report on ending this dependence leads to “sobriety” measures but also to new investments, which are difficult to quantify for France at this time.

9) Military expenditure

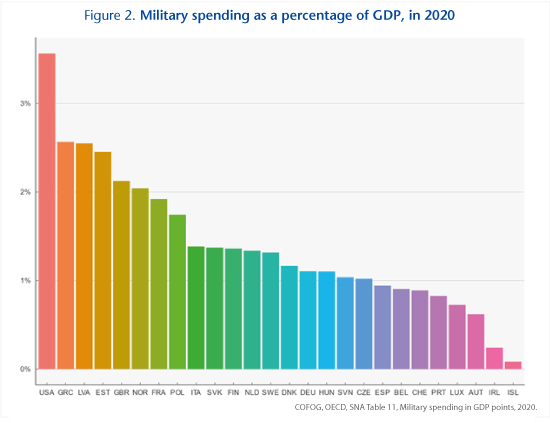

Another consequence of the war in Ukraine will be higher military spending. This will lead to medium-term investments, the economic effect of which will depend on how it is financed (by debt or taxes). Germany has announced a package of 100 billion euros to be used in the short term. France, on the other hand, already has a higher level of military spending and at present is sticking with a policy of increasing military spending by 3 billion euros per year.

10) Europe and European fiscal rules

The war in Ukraine will most likely lead to the suspension of European fiscal rules for another year, until 2024. The establishment of a common European debt is under discussion, but the outcome remains uncertain.

III – European Central Bank and monetary policy

11) The ECB is in a difficult situation, as it faces rising energy prices, falling activity and high levels of public debt

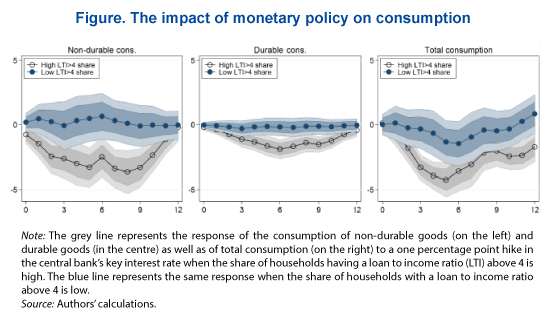

One point needs to be clarified: the rise in energy prices will certainly push up the price index and therefore average prices, but this primarily involves domestic impoverishment. In other words, the ECB cannot fight this energy cost-driven price increase (which will also push European entities to find ways to reduce their energy dependence). This price increase will lead to inflation if wages and other prices start to rise continuously after this initial impulse. In other words, it is against possible second-round effects, not first-round effects, that the ECB needs to fight. In contrast to the 1970s shock, it is unlikely that the rise in energy prices will lead to an inflationary spiral, due to the de-indexation of wages. However, the way in which the SMIC, the French minimum wage, is indexed should push it higher. A fiscal effort on behalf of people paid the minimum wage to compensate for higher energy costs does, however, make less relevant the increase in the SMIC induced by higher energy prices.

However, the current difficulty concerns the existence of some second-round effects upon exiting the Covid-19 crisis (irrespective of the price of the war in Ukraine), as core inflation was already at 2.7% in February, above the 2% target. It is therefore important that the absorption of the energy price shock does not lead to self-sustaining price increases.

Second, the ECB will have to deal with a new wave of financial instability, with possible contagion in the financial system and rising interest rates in some countries.

Finally, the most likely outcome is that the ECB will take steps to support public policy. The point is not so much to stimulate demand, which would be inappropriate in this kind of environment, but rather to avoid interest rate hikes in some countries, as is suggested by a reading of its statements in the 10 March ECB press conference. Indeed, the statement of Thursday 10 March and the reduction in the volume of securities repurchases go hand in hand with a vigorous affirmation of the fight against the fragmentation of the euro zone, and therefore against the rise in interest rate spreadswhich could destabilise highly indebted countries such as Italy. Our reading therefore is of an ECB policy of risk reduction without support for demand, which seems justified during the military conflict.

Conclusion

The war in Ukraine is a massive income shock that, without a public response, would lead to a fall in GDP of 2.5% and a rise in inflation of 3% to 4% in the highest estimate of a long-term rise in prices, without behavioural changes, but also without taking into account financial instability. Considering the low range of a short conflict reduces these effects by three-quarters, to a fall of less than 1 GDP point.

- Rising energy prices lead to anti-redistributive effects, which should lead in turn to budgetary efforts on behalf of poorer people.

- As a result, government support of at least 1 GDP point is likely, limiting the fall in GDP but pushing inflation into the high range.

- Financial instability is possible, which would substantially increase these effects, without taking into account of course any extension of the war into Europe outside Ukraine, which would completely change the method of estimation.