* Note from the editor: This text was initially published on 10 June 2008 on the OFCE site under the heading “Clair & net” [Clear & net] at a time when working on Sundays was a burning issue. As this is once again a hot topic, we are republishing this text by Xavier Timbeau, which has not lost its relevance.

In Jules Dassin’s cult film, Ilya, a prostitute working a port near Athens, never works on Sunday. Today, according to the Enquête emploi labour force survey, nearly one-third of French workers say they occasionally work on Sunday and nearly one out of six does so regularly. As in most countries, Sunday work is regulated by a complex and restrictive set of legislation (see here) and is limited to certain sectors (in France, the food trade, the hotel and catering industry, 24/7 non-stop manufacturing, health and safety, transport, certain tourist areas) or is subject to a municipal or prefectural authorization for a limited number of days per year. This legislation, which dates back more than a century, has already been widely adapted to the realities and needs of the times, but is regularly called into question.

The expectations of those who support Sunday work are for more business, more jobs and greater well-being. Practical experience indicates that revenue increases for retailers that are open Sundays. Conforama, Ikea, Leroy Merlin and traders in the Plan de Campagne area in the Bouches du Rhone département all agree. Up to 25% of their turnover is made on Sunday, a little less than Saturday. For these businesses, it seems clear that opening on Sunday leads to a substantial gain in activity. And more business means more jobs, and since there are also significant benefits for consumers, who meet less traffic as they travel to less congested stores, it would seem to be a “win-win” situation that only a few “dinosaurs” want to fight on mere principle.

Nevertheless, some cold water needs to be thrown on the illusions of these traders. Opening one more day brings more business only if the competition is closed at that same time. This is as true for furniture, books, CDs or clothes as it is for baguettes. If all the stores that sell furniture or appliances are open 7 days a week, they will sell the same amount as if they are open 6 days a week. If only one of them is open on Sundays and its competitors are closed, it can then capture a significant market share. It is easier to purchase washing machines, televisions and furniture on a Sunday than on a weekday. So anyone who opens on their own will benefit greatly. But ultimately consumers buy children’s rooms based on how many children they have, their age or the size of their home. They do not buy more just because they can do their shopping on Sunday. It is their income that will have the last word.

It is possible that a marginally larger number of books or furniture are sold through impulse buying on Sunday, if the retailers specializing in these items are open. But consumer budgets cannot really be stretched, so more spending here will be offset by less spending elsewhere. Year after year, new products, new reasons for spending, new commercial stimuli and new forms of distribution emerge, but these changes do not alter the constraints on consumers or their decisions.

In the case of business involving foreign tourists, who are passing through France, opening on Sunday could lead to an increase in sales. Tourists could spend less in another country or after they return home. But this positive impact is largely addressed by existing exemptions.

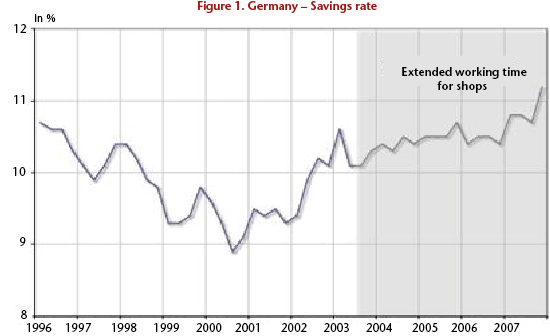

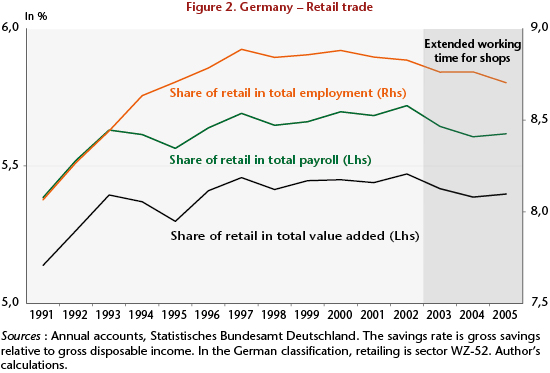

In 2003, the strict German legislation regulating retailer opening times was relaxed. This did not lead to any change in the population’s consumption or savings (Figure 1). Value added, employment and payroll in the retail sector stayed on the same trajectory (relative to the overall economy, see Figure 2). Opening longer does not mean consuming more.

The issue of Sunday opening is a matter of social time and its synchronization as well as consumer convenience and the freedom of the workforce to make real choices about their activities. Sunday work affects many employees, so expanding it is a societal choice, not a matter of economic efficiency.

Finally, the complexities of the legislation on Sunday work and its unstable character have led economic actors to adopt avoidance strategies. For example, in order to open on Sunday Louis Vuitton installed a bookstore (with travel books!) on the 5th floor of its Champs Elysées store (the other Louis Vuitton stores in Paris are closed on Sundays). Selling luxury bags thus became a cultural activity. Large food stores (which can open on Sunday morning) sell clothing and appliances, thus justifying other ways of working around restrictions by non-food retailers, who view this as unfair competition. These workarounds render the law unjust and distort competition with a legal bluff as cover.

Any change in the law should pursue the objective of clarification and not introduce new loopholes (as did the recent amendment of December 2007 to the Chatel law of 3 January 2008 extending earlier exemptions to include the retail furniture trade).

Homer, a cultured American on a visit to Athens, attempted to save Ilya from her sordid fate by introducing her to art and literature. But Homer was acting on behalf of a pimp from the Athens docks who wanted to put an end to the free-spirited Ilya’s subversive influence on the other prostitutes. When Ilya learned of this, she went back to her work: trading herself for money. Her dignity came from never doing it on Sunday.