This text draws on the article “Le piège de la déflation: perspectives 2014-2015 pour l’économie mondiale” [The deflation trap: the 2014-2015 outlook for the world economy], written by Céline Antonin, Christophe Blot, Amel Falah, Sabine Le Bayon, Hervé Péléraux, Christine Rifflart and Xavier Timbeau.

According to a Eurostat press release published on 14 November 2014, euro zone GDP grew by 0.2% in the third quarter of 2014, and inflation stabilized in October at the very low level of 0.4%. Although the prospects of a new recession have receded for now, the IMF evaluates the likelihood of a recession in the euro zone at between 35% and 40%. This dismal prospect reflects the absence of a recovery in the euro zone, which is preventing a rapid reduction in unemployment. What lessons can be drawn?

In the short term, this sluggishness is due to three factors that have held back growth. First, fiscal consolidation, although less extensive than in 2013, has been continued in 2014 in a context where the multipliers remain high. Second, despite the reduction in long-term public interest rates due to the easing of pressure on sovereign debt, financing conditions for households and businesses in the euro zone have worsened, as the banks have not consistently passed on the reduction in long-term rates and lower inflation is leading to a tightening of real monetary conditions. Finally, the euro appreciated by more than 10% between July 2012 and early 2014. Even though the currency’s rise reflects the winding down of pressure on euro zone bond markets, this has hurt exports. In addition to these short-term factors, recent data could herald the beginnings of a long phase of moderate growth and low inflation or even deflation in the euro zone.

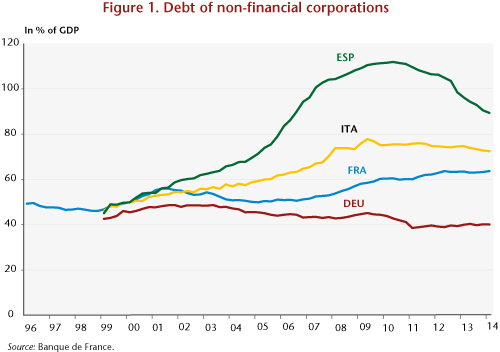

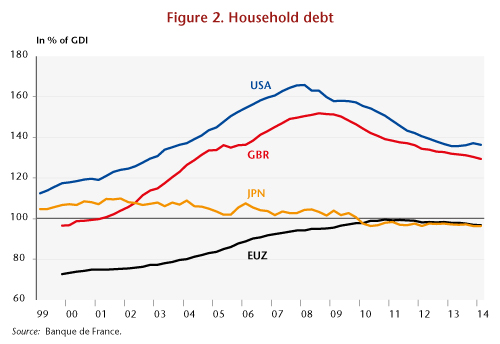

Indeed, after a period of sharply increasing debt (see Figures), the financial situation of households and firms in the euro zone has deteriorated since 2008 due to a series of crises – financial, fiscal, banking and economic. This deterioration in the financial health of the non-financial sector has weakened its thirst for credit. Furthermore, households may be forced to cut down on their spending on consumption, and firms investment and their need for employment in order to reduce their debt. Adding to this is the fragility of certain banks, which need to absorb a high amount of bad debt; this is leading them to restrict the supply of credit, as is evidenced by the latest SAFE survey conducted by the ECB on SMEs. In a context like this where private agents prefer deleveraging, fiscal policy should play a crucial role. But this is not happening in the euro zone due to the desire to consolidate the trajectory of public finances at the expense of the goal of growth[1]. Furthermore, while many countries could get out of the excessive deficit procedure in 2015 [2], fiscal consolidation is expected to continue because of the rules in the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance

(TSCG) requiring Member countries to make fiscal adjustments to bring public debt down to the 60% threshold within 20 years[3].

These conditions could push a recovery further down the road, and the euro zone could wind up locked in the trap of deflation. A lack of growth and high unemployment are creating downward pressure on prices and wages, pressure that is being exacerbated by internal devaluations, which are the only solutions being adopted to improve competitiveness and regain market share. This reduction in inflation is making the deleveraging process even more protracted and difficult, thus undercutting demand and strengthening the deflationary process. The Japanese experience of the 1990s shows that it is not easy to pull out of this kind of situation.

[1] The costs of this strategy were evaluated in the two preceding iAGS reports (see here).

[2] France and Spain would, however, constitute two major exceptions, with budget deficits of, respectively, 4% and 4.2% in 2015.

[3] See the post by Raul Sampognaro for more on the specific case of Italy.

Commentaires