By Pierre Madec and Xavier Timbeau

This evaluation of Universal Basic Income (UBI), the flagship proposal of French presidential candidate Benoît Hamon, highlights a potentially important impact of the measure on the living standards of the least well-off households and on inequalities in living standards. If implemented, a universal basic income would have the effect of making France one of the most egalitarian countries in the European Union. In return, the “net” cost of the programme could be high, around 45 to 50 billion euros. Given the measure’s cost, financing it through an income tax reform could make the French socio-fiscal system even more redistributive, but would lead to a considerable increase in the marginal tax rates borne by the wealthiest households.

By making it one of the flagship proposals of his election programme for the presidency, Benoît Hamon has revived the debate around a universal basic income (UBI). It is a radical project, the subject of numerous controversies (see, for example, Allègre and Sterdyniak, 2017), so the quantification of the programme is needed. Starting from Benoît Hamon’s proposal, which has been significantly modified in recent weeks, we attempt here, using a number of important assumptions (total or partial individualization, dependence on other social benefits) to make an initial evaluation. The idea here is neither to enter into the debate as to whether the modalities of application chosen are relevant, such as the exclusion of pensioners, nor to judge how close the proposal in its present form comes to an ideal of universality. Rather the aim is to avoid this type of debate and to qualify and quantify the effects of the implementation of the UBI as proposed by the presidential candidate.

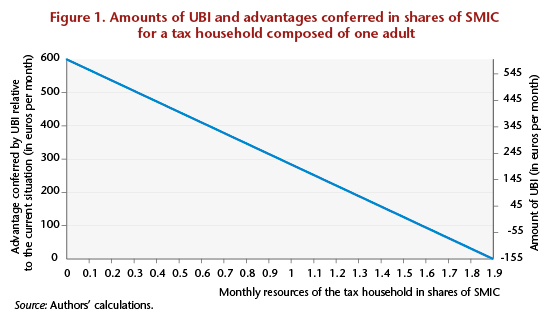

The latest version of the first step in the Universal Basic Income can be summarized as follows: “A basic income corresponds to a rise in net income that starts at 600 euros for people without resources and then disappears at 1.9 times the minimum wage (SMIC).”

Put like this, the proposal is for a differential allocation making it possible not to give rise to an artificial tax increase among those whose income situation is not changed by the universal income.

For married couples, the programme is not automatically individualized since it would still be possible to choose to maintain joint taxation. Couples with a family quotient that is less than the potential amount of the UBI should choose individualization. This is the case for couples with low incomes and not much income differential. Conversely, couples for whom the family quotient provides a bigger advantage than the basic income should choose to stick with joint taxation[1]. This would be the case for couples in which one of the individuals has a very high income and the other has no income[2].

For the most modest households the UBI replaces the RSA (income supplement for the working poor) and the Prime d’activité (working tax credit), and the calculation of social benefits (housing and family allowances, disabled adult allowance, scholarships, etc.) is not modified, as their amounts are included in the resources used to calculate the universal income.

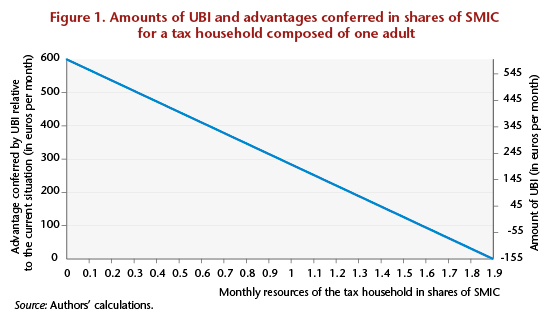

In the general framework, for all tax households whose gross resources are less than 1.9 times the SMIC, i.e. 2,800 euros gross per month, the UBI is equal to the difference between the base amount of 600 euros per month (7,200 euros per year) and 27.4% of the tax household’s gross resources. For non-taxable households, the UBI is considered a tax on negative income. For taxable households with gross resources of between 1.5 and 1.9 times the SMIC (3.8 SMIC in the case of a married couple), the UBI reduces the income tax due, thereby increasing the household’s disposable income, with this additional income cancelling out at 1.9 SMIC. The measure’s cost to the public finances for these households therefore corresponds to the difference between the amount of the UBI and the income tax currently paid. For tax households with gross resources of more than 1.9 times the gross SMIC (3.8 SMIC for married couples), the current system applies and there is no gain (Figure 1).

Formally, the monthly amount of UBI received by a tax household composed of a single adult and with resources of less than 1.9 times the gross SMIC is based on the following formula:

UBI = 600 – 0.274 x GR

GR, gross resources, corresponds to the gross taxable income, as defined in the tax code, of the tax household, increased by a factor of 1.33 used to approximate the conversion between taxable income and gross resources including charges and contributions, the tax base for the calculation of the UBI. In the case of a married couple, the UBI is calculated as follows, since the UBI as proposed is not then individualized:

UBI = [600 – 0.274 x GR/2] x 2

In order to measure the measure’s redistributive impact, we have drawn on the micro-simulation model of the DREES and INSEE known as INES ([3] see the box). As the last operational version of the model dates from 2015, the results presented must be interpreted In line with the legislation of 2015. In fact, measures such as the Prime d’activité credit, introduced in 2016, are not taken into account, in contrast to the Prime pour l’emploi in-work tax credit (PPE).

As of January 2018, people over age 18 who are still reported in their parents’ tax household and who are UBI eligible must leave their parents’ tax household in order to benefit from the UBI. It should be noted that this case is not dealt with in our evaluation, given the complexity of taking into account transfers between parents and children when they are not in the same tax household. We will therefore focus on households in which the reference person was aged between 18 and 64, i.e. 20 million households out of the 28.3 million total households in France, as the rest, pensioners, are not eligible for the measure.

The UBI has been modelled as an additional line in the calculation of income tax, with the amount of UBI being subtracted, subject to conditions of age, resources and marital status explained above, from the latter.

Subject to these assumptions, the UBI should benefit 11.6 million households in which the reference person is aged 18 to 64, at a gross cost of around 51 billion euros, i.e. an average of 4,400 euros per year and per beneficiary household.

The gross cost is not the cost to the public purse. Indeed, the implementation of the UBI would de facto lead to the elimination of the base RSA income supplement and the Prime d’activité tax credit from the tax-benefit system. In 2016, these two programmes had a fiscal cost of close to 15 billion euros (10 billion euros for the RSA and 5 billion for the Prime d’activité). Moreover, the interactions between universal income and these other social benefits are not yet completely set out in Benoît Hamon’s proposal[4]. If the amount received from UBI were to be taken into account for the calculation of the other social benefits, the amounts paid for these would fall significantly. The gross cost of universal income would remain unchanged, but savings could be realized on social benefits.

We assume here that the amount received in social benefits by the household is taken into account for the final calculation. In other words, we subtract from the amount of UBI received by the household 27.4% of the total amount of social benefits received in cash (housing and family allowance, scholarships, disabled adult allowance, etc., i.e. 32 billion euros per year for potential UBI beneficiaries). While including the benefits in the calculation of the amount of UBI is complicated by the structure of the microsimulation model, it is possible to estimate the reduction in the overall amount of UBI paid by taking into account total social benefits, about 6 billion euros.

If this option is chosen – which we assume in the absence of further clarification – UBI’s “net” cost, excluding the 18-25 year-olds fiscally reporting under their parents, would be on the order of 30 billion euros, which is close to the amount declared by the candidate, to which, once again, it will be necessary to add the amount owed to individuals between the ages of 18 and 24 who are currently reported fiscally by their parents. In 2015, of the 5.2 million individuals aged 18 to 24, 1.7 million were fiscally independent of their parents. The additional gross cost if no 18-24 year-olds were included on their parents’ tax statements would therefore be on the order of 25 billion euros, from which should be subtracted 27.4% of the scholarships (0.115 billion euros per year) and housing benefits paid (1.4 billion euros per year), as well as the tax benefits currently enjoyed by the parents of the said individuals (benefit of up to 1,500 euros per year and per child, to a maximum of 5.2 billion if all households are at the ceiling).

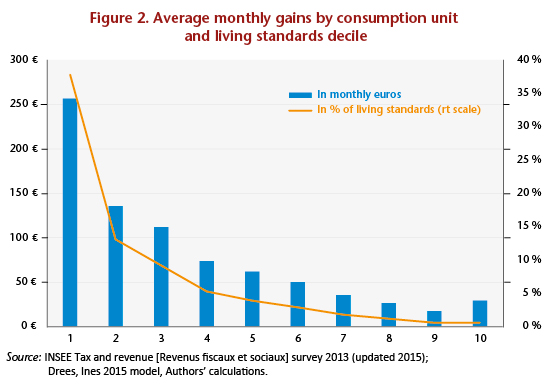

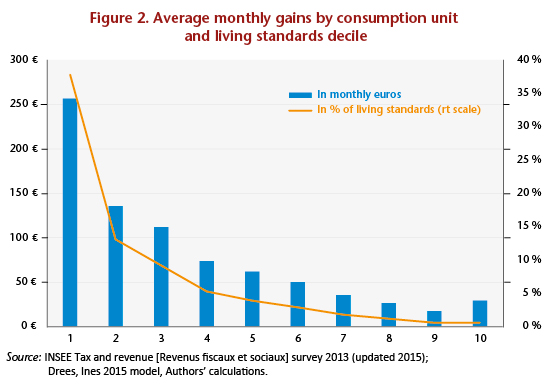

The measure, which is targeted at low-income households and not funded by an increase in household taxation or a decrease in social benefits, would have a positive impact on the bottom of the distribution of living standards (Figure 2) [5].

On average, households in the first decile of living standards should see their standard of living rise by 257 euros per month per consumption unit, i.e. a 38% increase in their average standard of living. The gain for households in the second decile should be roughly half as much, i.e. 137 euros per month per consumption unit, which represents a 13% increase in their average standard of living.

Given that, unlike many benefits, the UBI is allocated not to households but to tax households, some members (not taxed jointly but cohabiting as unmarried couples not in PACS civil partnerships) of some households in the upper deciles of the distribution of living standards should receive the UBI (and the highest decile more than the ninth decile due to a composition effect). In other words, there are tax households with low gross incomes among households with high living standards[6].

Based on these assumptions, the median standard of living would be raised by 3.6%, and the poverty rate, i.e. the share of French households with resources under 60% of the median level, i.e. about 1,000 euros / month / consumption unit, would come to 8.5%, versus 13.4% at present. The median standard of living of the poorest households – those with a standard of living below the poverty line – would rise by 11%. The intensity of poverty, measured as the relative gap between the median standard of living of the poor and the poverty line, would also fall by a third, from 17% today to 11%.

Finally, the Gini coefficient of living standards, an indicator of inequality, would be reduced by 0.04 to a level of 0.26, thus moving France from a median situation in terms of the Gini at the European level to being among the least unequal countries – the European median of the Gini in 2015 was 0.30 (and the lowest 0.25).

Excluding the young people (aged 18-24) reported on their parents’ taxes, the net cost of the UBI would be on the order of 30 billion euros. By adding them, subject to a more detailed assessment, the net cost would be on the order of 49 billion. This is a long way from the 400 billion once bandied about, but it is still not negligible[7]. If the UBI were to be financed by a reform of personal taxation, this would lead to a considerable increase in the marginal rates of the highest deciles of the income distribution. Note that personal income tax brings in 74 billion euros annually. Another tax base, such as wealth, could also be used, but this would lead to a significant hike in wealth taxes. Property taxes and the ISF wealth tax currently bring in a little less than 30 billion euros. Moreover, the redistributive effects of the UBI – which are significant, in our assessment – would be amplified by an increase in taxation that is already progressive.

_________________________________________________________________________

Box: The Ines micro-simulation model (Sources: INSEE, DREES)

Ines is the acronym for “Insee-Drees”, the two organizations that are jointly developing the model. The model is based on the INSEE’s Tax and Social Revenue surveys (ERFS), which include several hundred details on each individual and accurate and reliable data on income taken from tax returns. It can be used to simulate all recent legislative years using more recent ERFS years.

The model is used to carry out studies at annual intervals, but it is also used for in-depth studies in order to inform the economic and social debate in the areas of monetary redistribution, taxation and social protection. Finally, it is sometimes used to aid reflection in response to specific requests from various high government councils, supervisory ministries or control bodies (IGF financial inspectorate, Court of Auditors [Cour des comptes], Igas social inspectorate).

The Ines model simulates:

— Social charges and direct taxes: social contributions, CSG wealth tax, CRDS debt contribution and income tax (including the Prime pour l’emploi credit);

— Social benefits other than those corresponding to replacement income: personal aid for housing; the main social minima: the Revenu de solidarité active (RSA) income supplement; the Disabled adult allowance (AAH) and its complements; pension supplements and the Supplementary disability allowance (ASI); family benefits: the Family allowance (AF), the Family complement, the Back-to-school allowance (ARS) and high school scholarships, the Young child benefit (Paje) and its complements (Free choice of activity complement – CLCA – and Free choice of childcare complement – CMG), public subsidies for childcare in collective and family kindergartens, the Family support allowance (ASF) and the Disabled child education allowance (AEEH); and the Prime d’activité credit.

The main omissions relate to local taxes and subsidies (property tax, for example) and the Solidarity tax on wealth (IS). Retirement pensions, unemployment benefits and housing tax are not simulated but are presented in the data. Indirect levies are strictly speaking also outside the scope of the Ines model. The model simulates, using ranges, the different benefits to which each household is entitled and the taxes and levies that it has to pay. Ines draws on the INSEE’s Tax and Social Revenue surveys (ERFS), which bring together socio-demographic information from the Employment Survey, administrative information from the CNAF, the CNAV and the CCMSA, and details of the income reported to the tax authorities for the calculation of income tax.

Ines is a so-called “static” model: it does not take into account any changes in household behaviour, for example in terms of birth rates or labour market participation, which could be induced by changes in tax-benefit law. Since 1996, the model has been updated annually during the summer in order to simulate the most recent legislation and cover the preceding year. For example, in the summer of 2016, Ines was updated to simulate the legislation for 2015. Based on these updates, the INSEE and DREES teams contribute annually to the INSEE’s Social Portrait, in which they analyse the redistributive balance sheet for the tax and benefit measures enacted during the preceding year. The latest publication is entitled “Tax and benefit reforms in 2015 are leading to a slight redistribution from the richest 30% to the rest of the population” (André, Biotteau, Cazenave, Fontaine, Sicsic, Sireyjol).

______________________________________________________________

[1] Recall that the family quotient gives entitlement to a maximum tax reduction of 30,000 euros per year. The abolition of the family quotient would yield 5.5 billion euros (HCF, 2011) but would cost all the UBI paid to partners with a lower income who have chosen individualization.

[2] We have chosen not to take into account these tax optimization mechanisms within households, but it is understood that this means the evaluation proposed for the cost of the measure is underestimated.

[3] The source code and documentation for the INES micro-simulation model was opened to the public in June 2016 (https://adullact.net/projects/ines-libre). We have been using the 2015 open access version since 1 October 2016.

[4] In particular, the use of a micro-simulation model such as INES makes it possible to explore the consequences of different choices that can be made about the situation of the persons covered, the net redistribution effected and what has to be financed. A change in the rules for allocating or calculating a social benefit can have significant impacts on the net cost and the redistributive effects.

[5] The proposed measure significantly alters the distribution of living standards. Due to this, some households see their membership in a decile of living standards change positively or negatively. The deciles are maintained here at their pre-reform level.

[6] By way of illustration, the average age of the reference persons in households in the upper decile of the standard of living benefiting from the UBI is over 55. It can thus be assumed that these households are home to young adults who are fiscally independent but have few resources.

[7] The evaluation presented here is called “static”. It therefore does not take into consideration any possible changes in individual behaviour with respect to employment due to the impact of this measure.

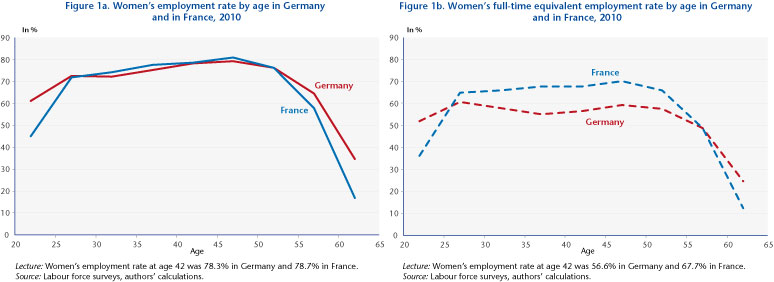

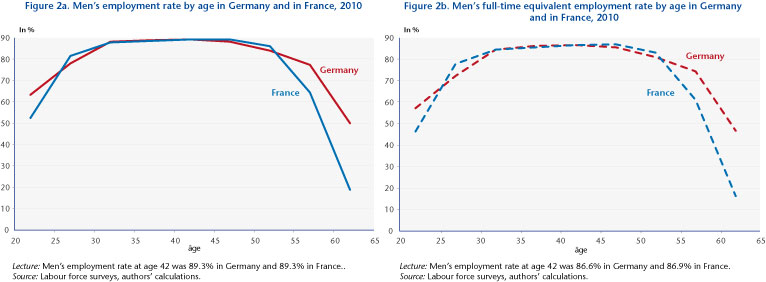

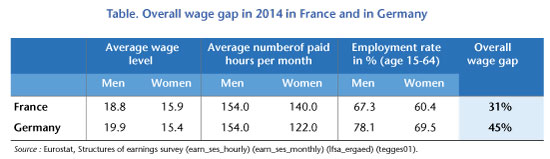

Thus policies aimed at occupational equality cannot leave aside the issue of working time and the quality of the jobs held by women. It seems that from this point of view France is doing better than Germany, although much remains to be done in this area.

Thus policies aimed at occupational equality cannot leave aside the issue of working time and the quality of the jobs held by women. It seems that from this point of view France is doing better than Germany, although much remains to be done in this area.

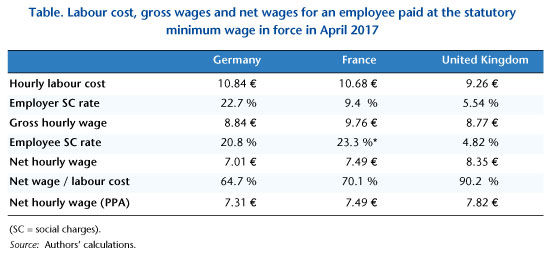

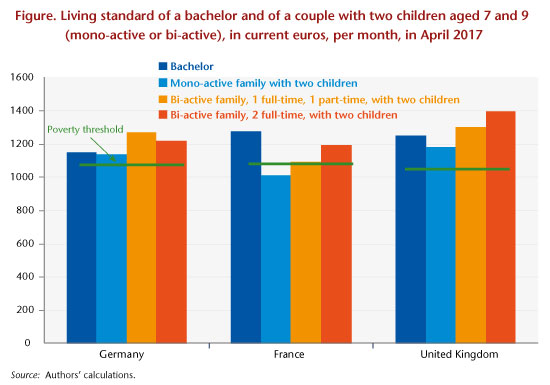

From the point of view of the relative position of minimum wage earners in relation to the general population, our study highlights the rather favourable situation of the United Kingdom. The living standard there is comparatively high: all the families considered in our typical cases have a standard of living above the poverty line, on the order of 30% higher for a family where both parents work full-time at the minimum wage. The gain from taking up a job is, as in France, high, while it is low in Germany in all the configurations.

From the point of view of the relative position of minimum wage earners in relation to the general population, our study highlights the rather favourable situation of the United Kingdom. The living standard there is comparatively high: all the families considered in our typical cases have a standard of living above the poverty line, on the order of 30% higher for a family where both parents work full-time at the minimum wage. The gain from taking up a job is, as in France, high, while it is low in Germany in all the configurations.

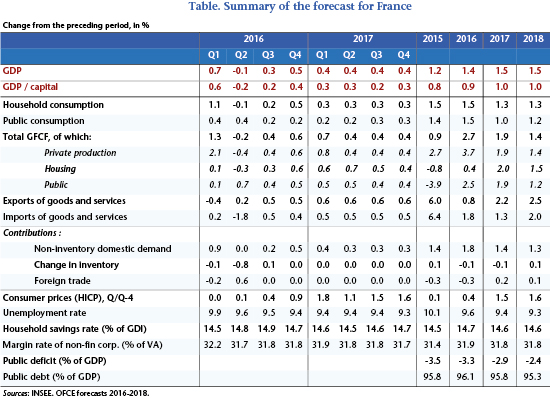

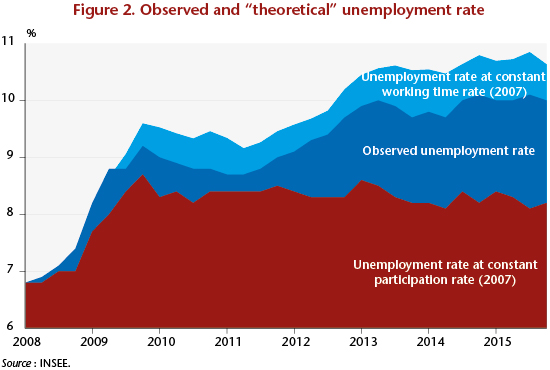

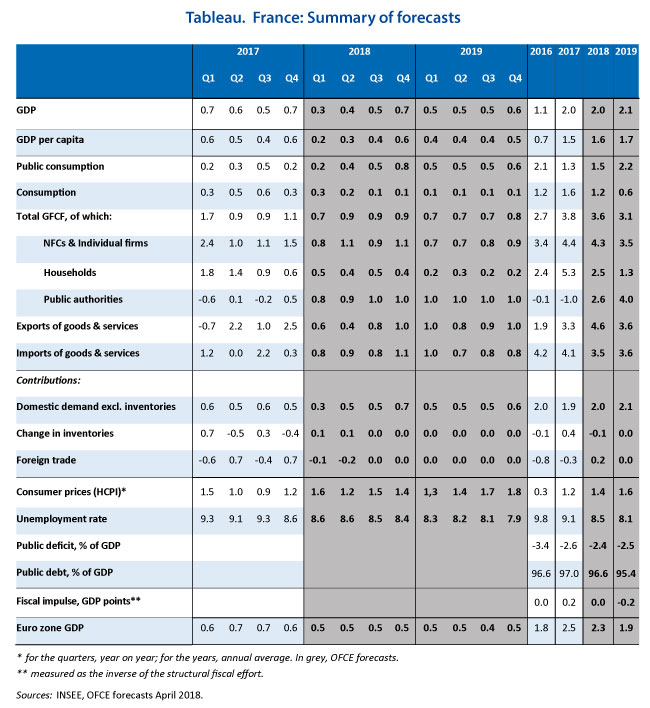

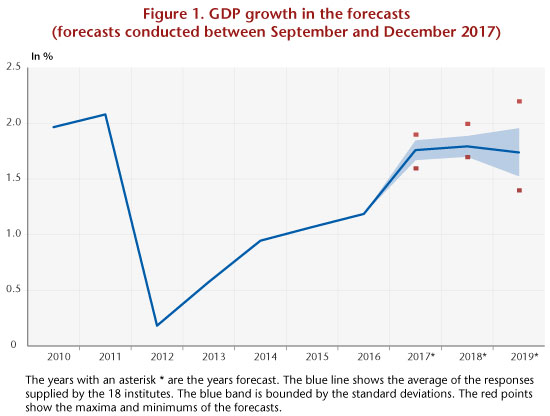

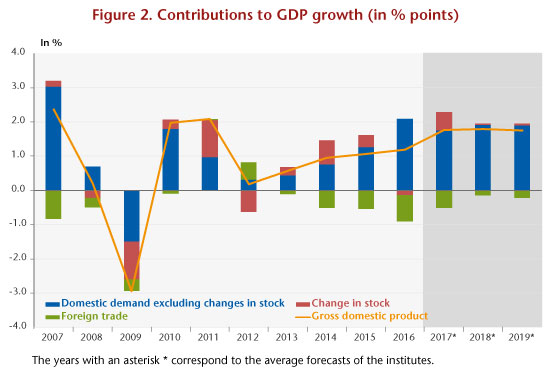

There is also debate over the forecasts for jobs and wages, in particular over the impact of the cutbacks in subsidized jobs, the effect of the policies to lower labour costs in 2019 (transformation of the CICE competitiveness tax credit into lower employer social contributions) and productivity (trend and cycle). On average, the unemployment rate should fall from 9.5% in 2017 to 8.8% in 2019, with forecasts ranging from 8.1% for the most optimistic to 9.2% for the most pessimistic. Some differences in the forecasts on wages can be attributed to differing assessments both of the degree of tension on the labour market and also of the impact on wages of the more decentralized collective bargaining set up in 2017. Wages are expected to rise by 1.8% in 2017 and on average by 1.9% in 2018 and 2% in 2019 (ranging from 1.3% for the lowest forecast to 2.6% for the highest).

There is also debate over the forecasts for jobs and wages, in particular over the impact of the cutbacks in subsidized jobs, the effect of the policies to lower labour costs in 2019 (transformation of the CICE competitiveness tax credit into lower employer social contributions) and productivity (trend and cycle). On average, the unemployment rate should fall from 9.5% in 2017 to 8.8% in 2019, with forecasts ranging from 8.1% for the most optimistic to 9.2% for the most pessimistic. Some differences in the forecasts on wages can be attributed to differing assessments both of the degree of tension on the labour market and also of the impact on wages of the more decentralized collective bargaining set up in 2017. Wages are expected to rise by 1.8% in 2017 and on average by 1.9% in 2018 and 2% in 2019 (ranging from 1.3% for the lowest forecast to 2.6% for the highest).