Christophe Blot and Sabine Le Bayon

Can Germany avoid the recession that is hitting a growing number of countries in the euro zone? While Germany’s economic situation is undoubtedly much more favourable than that of most of its partners, the fact remains that the weight of exports in its GDP (50%, vs 27% for France) is causing a great deal of uncertainty about the country’s future growth.

Thus, in the last quarter of 2011, the downturn in the German economy (-0.2%) due to the state of consumption and exports has upset hopes that the country would be spared the crisis and that it could in turn spur growth in the euro zone based on the strength of its domestic demand and wage increases. Exports of goods fell 1.2% in value in late 2011 over the previous quarter, with a contribution of -1.5 points for the euro zone and -0.4 points for the rest of the European Union. Admittedly, the beginning of 2012 saw renewed growth, with GDP rising by 0.5% (versus 0% in the euro zone). Once again this was driven by exports, in particular to countries outside the euro zone. The prospects of a recession across the Rhine in 2012 thus appear to be receding, but there is still great uncertainty about how foreign trade will be affected in the coming months and about the extent of the slowdown “imported” into Germany. The question is whether the improvement in the first quarter of 2012 is temporary. The decline in manufacturing orders from euro zone firms to Germany (-7.5% in the first quarter of 2012, after -4.8% in the last quarter of 2011) could spell the end of German’s persistent growth, especially if the recession in the euro zone continues or worsens.

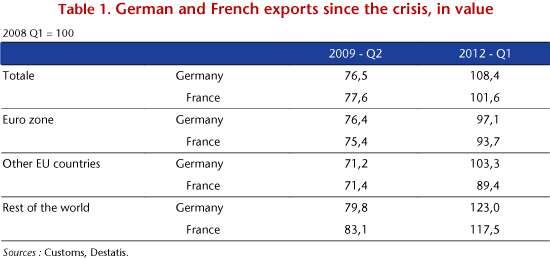

With GDP per capita above the pre-crisis level, Germany has been an exception in a euro zone that is still profoundly marked by the crisis. The country’s public deficit is under control, and it already meets the 3% threshold set by the Stability and Growth Pact. Germany is still running a foreign trade [1] surplus, which came to 156 billion euros (6.1% of GDP) in 2011, whereas at this same time France ran a deficit of 70 billion euros (3.5% of GDP). Despite Germany’s favourable foreign trade performance, the crisis has left scars, which today are being aggravated by the energy bill. For instance, before the crisis the trade surplus was 197 billion euros, with over 58% from trade with partners in the euro zone. With the crisis, activity slowed sharply in the euro zone — the zone’s GDP in the first quarter of 2012 was still 1.4% lower than the level in the first quarter of 2008 — which is automatically reflected in demand addressed to Germany. Thus, exports of goods to the euro zone are still below their level of early 2008 (down 2.9% for Germany and 6.3% for France, see Table 1). Germany’s trade surpluses vis-à-vis Italy and Spain — two countries that were hit hard by the crisis — have fallen significantly, mainly due to lower demand from the two countries. German exports to these two countries have decreased by 27% and 4% respectively since 2007.

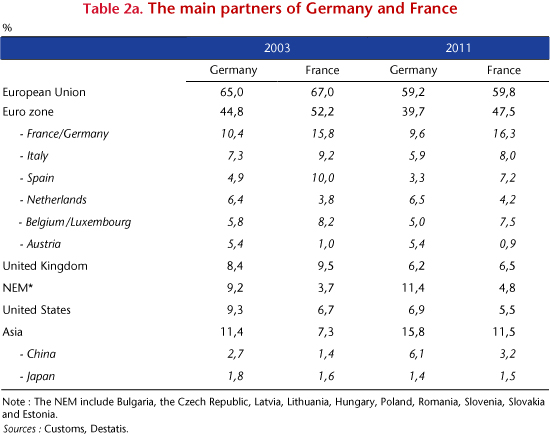

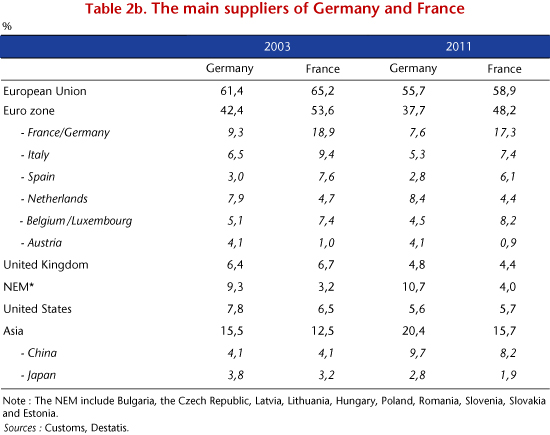

Nevertheless, although Germany is more exposed to foreign trade shocks than France, it is less exposed to the euro zone. The share of euro zone countries in German exports fell from 44.8% in 2003 to 39.7% in 2011 (Table 2a). In France, despite a fall on the same order of magnitude, 47.5% of exports are still directed towards the euro zone. When the European Union as a whole is considered, however, the gap disappears, as the EU represents 59.2% of German exports compared with 59.8% of French exports. The lower level of dependence on the euro zone has been offset by increasing exports to the new member states of the European Union (the NEM), with which German trade reached 11.4% in 2011. Moreover, Germany has maintained its lead over France on the emerging markets: in 2011 Asia represented 15.8% of German exports and China 6.1%, against 11.5% and 3.2% in the French case. By managing to diversify the geographical composition of its exports to areas experiencing vigorous growth, Germany has been able to dampen the shock of the slowdown in the euro zone. This can be seen in recent trade trends: while Germany’s exports (like France’s) have surpassed their pre-crisis level, this was due to exports to countries outside the euro zone, where Germany has benefited more than France (Table 1). Germany has in fact succeeded in significantly reducing its deficit with Asia, which has helped to offset the poor results with the euro zone and with Central and Eastern Europe. Finally, Germany has advantages in terms of non-price competitiveness [2], which reflects the dynamism of trade in automobiles and electrical, electronic and computer equipment. The surpluses in these two sectors regained their pre-crisis level in 2011 (respectively, 103 and 110 billion euros in 2011), whereas the balances in these two sectors have continued to deteriorate in France.

Even if orders from countries outside the euro zone remain buoyant (up 3.6% in early 2012), the weight of the euro zone is still too strong for exports to emerging markets to offset the decline in orders placed by the euro zone to Germany. This will inevitably affect the country’s growth. GDP should therefore rise less rapidly in 2012 than in 2011 (0.9% according to the OFCE [3], following 3.1%). Germany might thus avoid a recession, unless the euro zone as a whole experiences even sharper fiscal contraction. Indeed, the slowdown in growth means that the euro zone member states will not be able to meet their budget commitments in 2012 and 2013, which could lead them to decide on further restrictive measures, which would in turn reduce growth throughout the zone, and therefore demand addressed to the zone’s partners. In this case Germany would not avoid a recession.

Finally, the role of foreign trade is not limited to growth and employment. It could also have an impact on negotiations between France and Germany about the governance of the euro zone. The relative growth of the two countries will in practice affect the balance of power between them. The expected slowdown in growth in Germany clearly reflects its conflicting interests between, on the one hand, maintaining its market opportunities and, on the other, its fears vis-à-vis the functioning of the euro zone and the cost to public finances of broader support for the countries in greatest difficulty. While up to now the latter consideration has dominated the German position, this could change once its commercial interests come under threat, especially at a time when the German Chancellor is negotiating with the Parliamentary opposition about the ratification of the fiscal pact – an opposition that could demand measures to support growth in Europe, as has the new French president.

[1] Measured by the gap between the export and import of goods.

[2] See also J.-C. Bricongne, L. Fontagné and G. Gaulier (2011): “Une analyse détaillée de la concurrence commerciale entre la France et l’Allemagne” [A detailed analysis of commercial competition between France and Germany], Presentation at the Fourgeaud seminar [in French].

[3] This figure corresponds to the update of our forecast of April 2012, which takes into account the publication of the growth figures for Q1 2012.